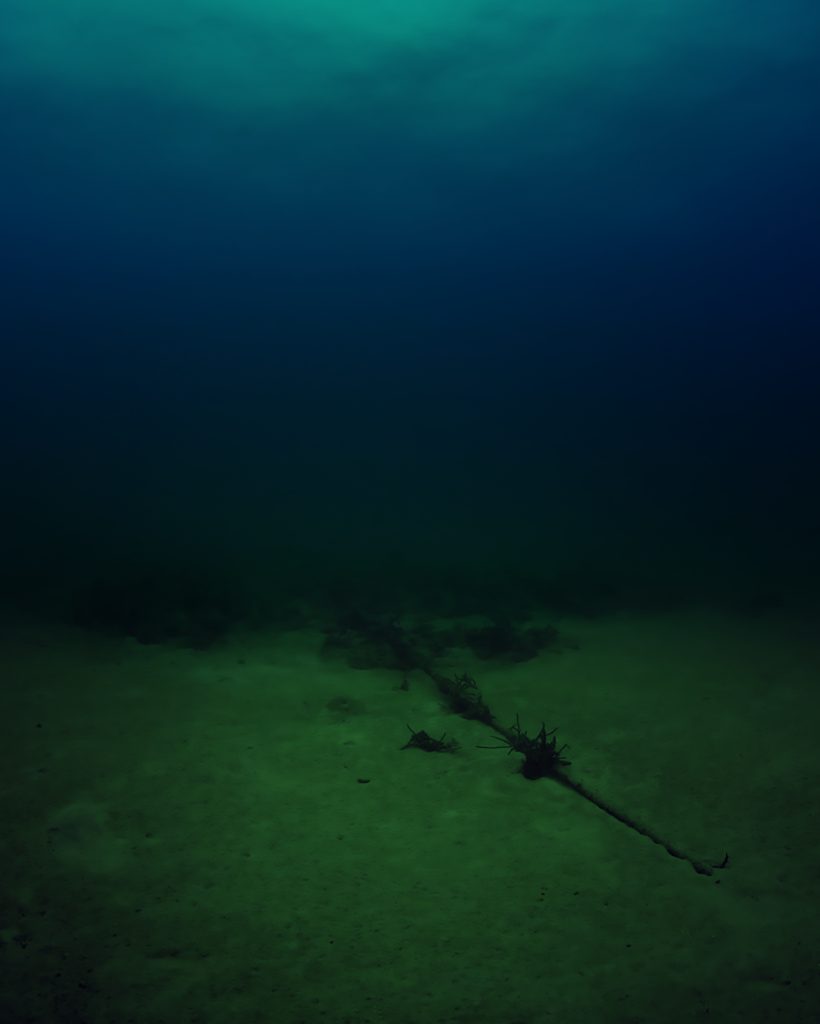

Welcome to the end. The end of world, maybe — though more certainly the end of the exhibition. In a matter of speaking, “Sites Unseen” traces the end of perception — when sight is replaced by surveillance — and, in a sense, sees the end as that of a visual limitation as technology increasingly takes over the eye’s narrow scope. Maybe this also suggests the end of art, as science-‘worthy’ objects developed in conjunction with aerospace engineers hang statically in gallery space. Or perhaps it is the end of science, now that sculpture is posited as something to be put into low-earth orbit. In Trevor Paglen’s recent exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, “Sites Unseen,” the end is not a destination but rather a feeling that permeates the atmosphere. Heavy as the millpond moonlight in long-exposure photographs of inaccessible military sites (They Watch the Moon, 2010), indistinct images of deep-sea cables tapped by the NSA (Bahamas Internet Cable System (BICS-1) NSA/GCHQ-Tapped Undersea Cable Atlantic Ocean, 2015) unearth a claustrophobic feel of staring into fathomless space without a clear idea of what is staring back (Untitled, (Reaper Drone), 2010). Presumably, the idea is that we should be concerned about the mechanisms and thematics that underpin the way we understand “the end of things”; we should consider what goes on beyond the limits of black sites, what covert operations have lead to our given state of affairs, and what technologies of control govern our daily lives. After all, if not the end of the world, it appears that the end of democracy is inexorably approaching. It has been said of Paglen’s work that the artist does not seek to expose the sovereign state’s secrets but to close in on the discomfiting space between ourselves and reality as it is given to us — that the work is about approaching “invisibility” instead of dismantling it. Like John Milton’s hell, Paglen’s work offers “no light, just darkness” — which more specifically exists as lambent negations disguised as landscapes, holding within restive questions yet settling for aestheticizing them.

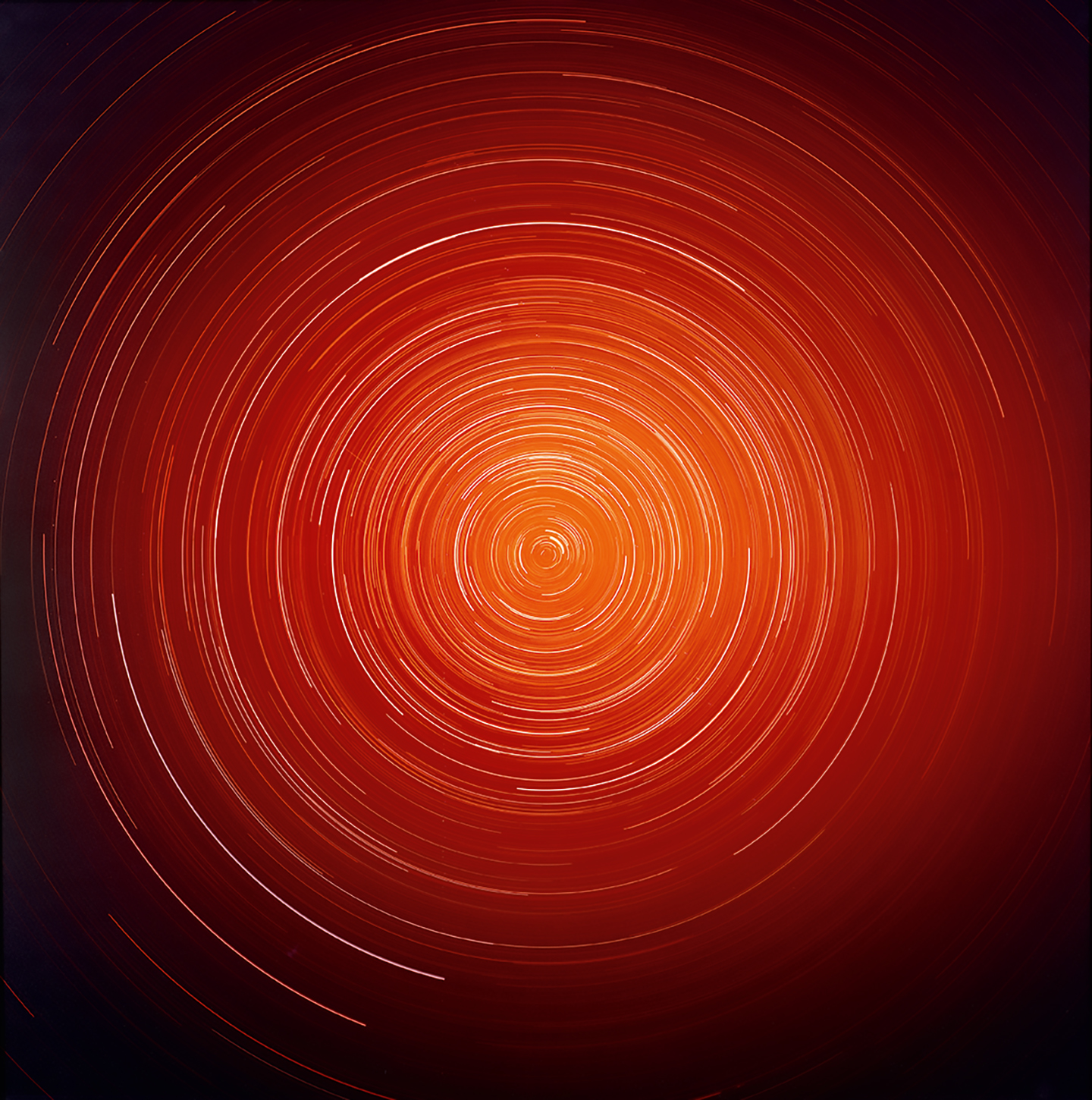

Photographic prints such as the techno-sublime, Rothko-esque The Sun, Linear Classifieror the data-driven portrait of Franz Fanon, ‘Fanon’ (Even the Dead Are Not Safe) Eigenface(both 2017), hang heavy in the space as decontextualized surrogates for machine vision and uncanny sights. Perhaps the atmospheric sense of an ending is merely that of specificity — or an aesthetic collapse. A mirrored orb hangs from the ceiling captivating its audience in the center of the exhibition, Prototype for a Nonfunctional Satellite (Design 4; Build 4)(2013) — recalling in its omniscient gaze Olafur Eliasson’s 2003 Turbine Hall piece The Weather Project. Under its reflection, the museumgoer is lulled into complacency, almost certainly more enamored by the marvels of modern fabrication than fearful of its ramifications. Albeit inadvertently, “Sites Unseen” recalls the central conflict in Lars von Trier’s 2011 film Melancholia, in which manic-depressive Kirsten Dunst and her well-to-do sister Charlotte Gainsbourg are coupled together to cope with the apocalypse as a meteorite approaches Earth. Dunst, familiar with the existentially iffy feeling of being at the edge of everything ending, deals with the situation with calm acceptance and curiosity. Gainsbourg, having vested so much in this idea of life and its longevity, falls to pieces. Walking through a survey of Paglen’s works is somewhat similar in its philosophical challenge: as an educated viewer, it is difficult to see beyond the indifferent spectacle of it all. But perhaps some, rightly so, feel the alarm.