In 2013, a mostly full audience at the Hammer Museum watched ITSOFOMO (In the Shadow of Forward Motion), David Wojnarowicz’s 1989 collaboration with the composer Ben Neill.

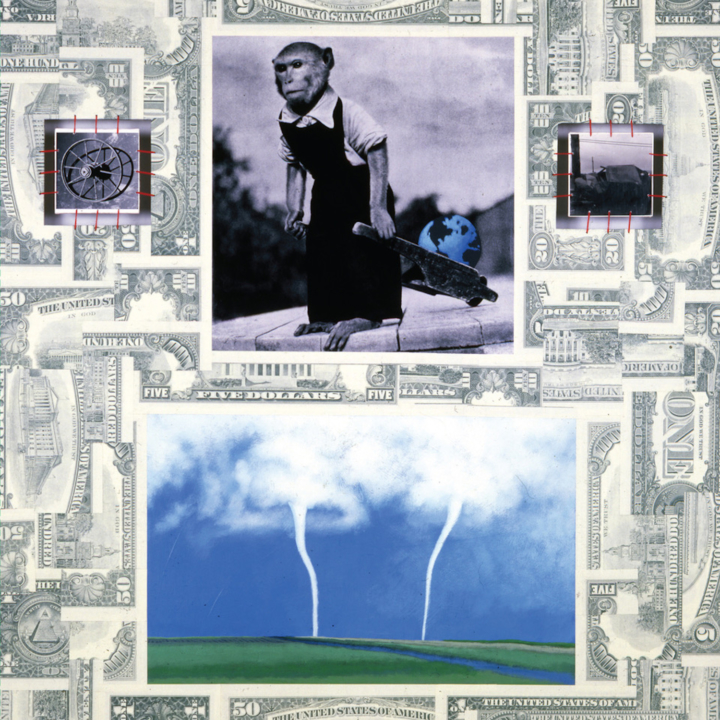

The projector screen was broken up into four rectangles, staccato video clips filling each one. They were exemplary Wojnarowicz images: animals fighting, swooping close-ups of books, ants running wild over objects. The oppositions and matches made between the four different channels are slippery and forceful, the film nearly ungraspable but deeply resonant. I liked it, but I was stuck on the soundtrack. Wojnarowicz’s voice, a dry-throated whisper, opened the piece, a straight line cutting through an uneasy, ambient soundscape. I remember almost straining to keep within comprehension of his words, when a thunderous drum hit cut through, startling the whole room. The music stretched and careened through defiance, tenderness, and rage. Before long, the latter of these moods took over, an onslaught of sound, Wojnarowicz’s full-throated voice hammering through the text. It was a powerful, familiar kind of music, but hard to locate in the late 1980s it emerged from, feeling closer to the skinless, patient humanity of post-Y2K omnivores like Xiu Xiu or Blood Orange. I thought about the music for a few days before attempting a furtive internet search for a bootleg of the video, thinking I could scrape off the music the same way I recorded Sub Society and Operation Ivy songs off skate videos as a kid.

So, I was surprised to discover a CD of ITSOFOMO, released by an Italian label in 1992. I spent too much on a secondhand copy via eBay and listened to it for a full year before reaching out to Ben Neill to see if he’d be interested in working on a reissue of the CD. I thought an LP would be a nice nod to the era it was made in, and hoped that breaking up the five movements across two records would give the listener some breathing room. After four years of discussion, tape transfers, lost masters, and occasional dismay at the continued relevance of Wojnarowicz’s indictments, ITSOFOMO came out on October 22, 2018. Ben and I spoke about the original piece and his perspective on it now.

Ethan Swan: We just made an LP record of ITSOFOMO. The piece was first presented at the Kitchen, a live performance with dancers and video and props. There was a CD in 1992, and there’s a version that’s shown as a screening, which is how I first saw/heard the work. Is there one that feels like the definitive version to you?

Ben Neill: I feel like the definitive version was the one performed by David, percussionist Don Yallech, and me along with David’s four videotapes. The original Kitchen performance was cut back for both aesthetic and practical reasons: David was not happy with the dance and theatrical elements, and it was impractical to tour with the sculptures/props. The trio was more like a rock band with the four videos; it was more visceral and direct and seemed more suited to the content. I also performed the piece with David a few times without the live percussion, but the trio with the live music and video was definitely the most complete realization. The CD was a multitrack recording of a live performance, which captures the audio very well, but I think the four-video version with the recorded music that I created in conjunction with the Hammer Museum a few years ago is the fullest representation.

ES: Sylvère Lotringer did that great interview with you that untangles the history of the piece, how you and David had worked together on the cover of your debut LP, and, when you subsequently had an invitation to perform at The Kitchen in New York, you asked David if he wanted to be part of it. Did you know David had been in 3 Teens Kill 4? What led you to making that invitation? Were you surprised by his performance?

BN: David mentioned that he had performed with a band in the past, but I never saw any of their shows. The performance idea was a natural outgrowth of our conversations once we realized that we had a lot of common ideas. I didn’t know what his performance would be like, but as we started developing the piece, I could see that he had an extremely strong presence as a performer. His voice was incredibly rich and he utilized it fully, literally going from whispers to screams during the performances.

ES: What about your own background, and how it led to this piece? Before you moved to New York you were involved in punk and new wave scenes in Ohio, and after you arrived you connected with Jon Hassell and La Monte Young. I think about the harshness of ITSOFOMO and its tension and its force. I can imagine you felt at home in all of that, but I can also see it all as very challenging. Did you feel ready to make this piece? Did this collaboration push you into new places?

BN: My background as a musician was as a trumpet player. I had a classical training, but I was also very passionate about popular music and also had a strong interest in the visual arts. Writing my own music was kind of a reaction against my classical training. I was interested in doing something musically that was more connected to the cultural milieu of my own era, and classical music seemed too limiting. The punk/new wave scene of Northeast Ohio was the first context where I created my own music and started working on what became mutantrumpet [a hybrid electro-acoustic instrument invented by Neill]. When I moved to New York in 1983 I decided to focus on developing a solo composer/performer project centered on the new instrument that would bring these two disparate sensibilities together. Robert Moog was assisting me with the electronics — he was a great supporter — and Jon Hassell’s work had been a big inspiration to me for years. I contacted Jon through his record label and we started getting together. He introduced me to La Monte Young and Rhys Chatham, who were both important in my development. I started studying with La Monte and performing his music, and also played in Rhys’s guitar ensemble. Rhys was very focused on the idea of merging classical avant-garde ideas with the energy and volume of punk, which reinforced my creative instincts. As I worked more with La Monte I got a better understanding of just intonation and frequency ratios, and I started incorporating those numerical structures into my pieces based on a concept I called rhytharmonics. Basically the idea was to apply the ratios of just intonation to all aspects of a composition rather than just pitch: rhythm, duration, tempo, and large-scale form. All of my work in the ’80s was blending these numerical, conceptual structures with rock and later dance music using the mutantrumpet as the performance vehicle. ITSOFOMO is probably the most complex piece I’ve ever created in terms of its numerical structure, and also perhaps the most visceral, so I would say it really drew together the two sensibilities that I had been working with for about a decade. I had huge respect for David’s vision and ideas, and I think the tremendous depth and scope of his work pushed me to be more ambitious and expansive in our collaboration.

ES: You sent me a 1993 review of the CD published in Variant magazine which describes the piece as “exhausting yet exhilarating,” and another time you mentioned a review that describes the record as having “a real sense of physicality.” Don’s percussion plays a role in this, but I think the whole piece is built to keep the listener very present. Does that grow out of the initial discussions you and David had about “forward motion” and how to enact it in the piece? I also wonder if this plays into bigger themes you’ve explored throughout your life, like the support you’ve given to Hyperdub and this kind of electronic music that uses volume and bass to create a physical connection to the body.

BN: I think the physicality stems from several places, the most obvious being the powerful content of the texts and the way David delivers them, particularly in the last section. The overarching concept of ITSOFOMO was the idea of acceleration. We wanted to implement that structure on many different micro and macro levels with the hope of generating a strongly physical experience for the audience through the combination of text, music, and video. One of my main reasons for working with just intonation and frequency ratios was their power to create stronger physical sensations and psychological states. The resonances of whole-number ratios are powerful, and I was implementing them across all of the aspects of composition with the goal of generating more visceral experiences. The instrumentation reinforced the sonic physicality; the large percussion battery with timpani was powerful by itself, and the electronics were all live, run from an Atari 1040 ST computer. The timpani were set up to trigger electronics, and David, Don, and I all had individual control of processing our sounds with upward glissando effects, which were another manifestation of acceleration through increasing frequency. There are a lot of long, slow accelerations throughout the piece that are pushing forward almost subliminally, as well as other points where the increasing speed becomes more frenzied. These phenomena are demonstrated in the music as well as the video, and I think this creates a sense of engagement, of being pulled forward by the piece. My subsequent involvement with various popular electronic music genres such as illbient, drum and bass, breaks, and dubstep certainly connects to the kind of experience that we were exploring in ITSOFOMO. I have become even more focused on the visceral side of things in recent years, not as focused on complex numerical systems as before; although there is always something of that structure, it’s not as rigorously implemented.

ES: In Cynthia Carr’s biography of Wojnarowicz, she mentions a last-minute addendum to the program for ITSOFOMO at the Kitchen, which added facts and statistics about AIDS. What was it like making art in that context? Did it feel constructive? Cathartic? Part of a bigger program?

BN: The time leading up to the premiere was a whirlwind. I don’t remember the exact sequence of events, but David had been diagnosed with AIDS, the Artists Space catalogue episode was in full swing, and generally the AIDS crisis had reached a fever pitch. ITSOFOMO felt like a very cathartic experience that was channeling all of that energy — it was kind of dizzying. Going back to my experiences in punk rock, I had always been interested in creating art that had strong social relevance for its time, and ITSOFOMO definitely had that more strongly than anything else I’ve ever done.