On the fifth floor of Rubin & Chapelle’s textile warehouse in Chelsea, Atalay Yavuz presents an array of enigmatically approachable recent sculpture. The exhibition, “how to make the perfect creme brulee,” both takes as its subject and actively performs a lineage of mental and emotional states as embodied by the shared presence (or absence) of other mind-bodies. Lighthearted, delicately handled, and casual in tone, the artist’s work follows through on a clearly conceived and illustrated trajectory that unfolds at well-paced increments.

“It’s a special day because I’m sharing with you my favorite dessert on earth. Mmm…Crème Brûlée. It’s even fun to say, even if it is a pain in the neck to type. I’ve loved it for a very, very, very long time.”

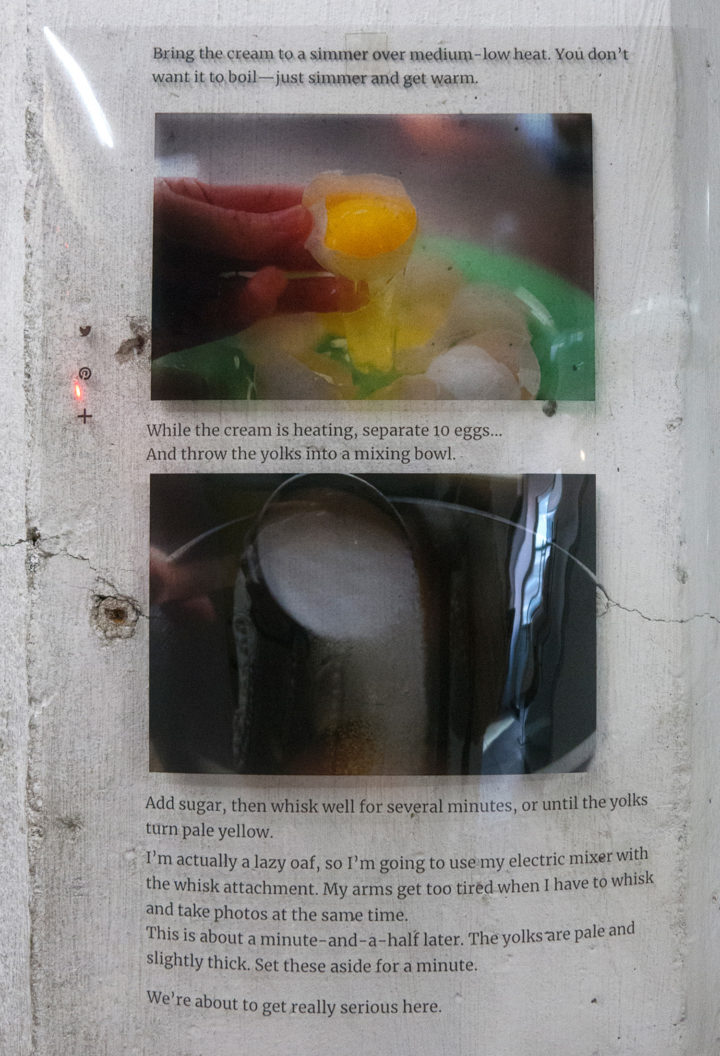

Distributed on the walls throughout the warehouse space are nine inkjet-printed transparencies, titled how to make the perfect creme brulee (2018), which contain content taken from a food blog the artist found online. Their text and images detail, in an emphatically enthusiastic voice, how to go about producing the custard-based dessert. A simple yet nuanced process, the offered narrative description comes imbued with a particularly charming spark of charisma and is sprinkled with moments of giddy anecdotal indulgence. The author’s playful diligence seems well aligned with Yavuz’s own sensibility, reflected in a seemingly nonchalant approach to conceiving and executing his curiously deep-seated works.

“I’m getting ready to make Crème Brûlée and I can’t stand not sharing it on my website.”

The appropriated recipe instructions, broken up as serial prints and affixed to the walls unframed, seem to parody didactic institutional wall text. These meander around the space and purport to accompany nearby sculptures as related information. As hilarious as they are instructional, the allure of the excerpted text lends the piece a performative power upon recontextualization. An innocently radiating positivity becomes paramount, and elevates its presence from something perhaps otherwise supplementary to a structurally significant element by way of its role in uniting all else on display as a single, considered installation. Falling out of a clear or strict sequence, this dismissal of accurately reproduced continuity poses no real issue, and the inverted use of wayfinding allows one to take better note of the delineated regions that organize the homogenous groupings of sculpture, somehow working to facilitate a rather smooth navigation amid the sometimes amorphously abstract links and multidirectional pathways the artist seems to be offering.

“I’m actually a lazy oaf, so I’m going to use my electric mixer with the whisk attachment. My arms get too tired when I have to whisk and take photos at the same time.”

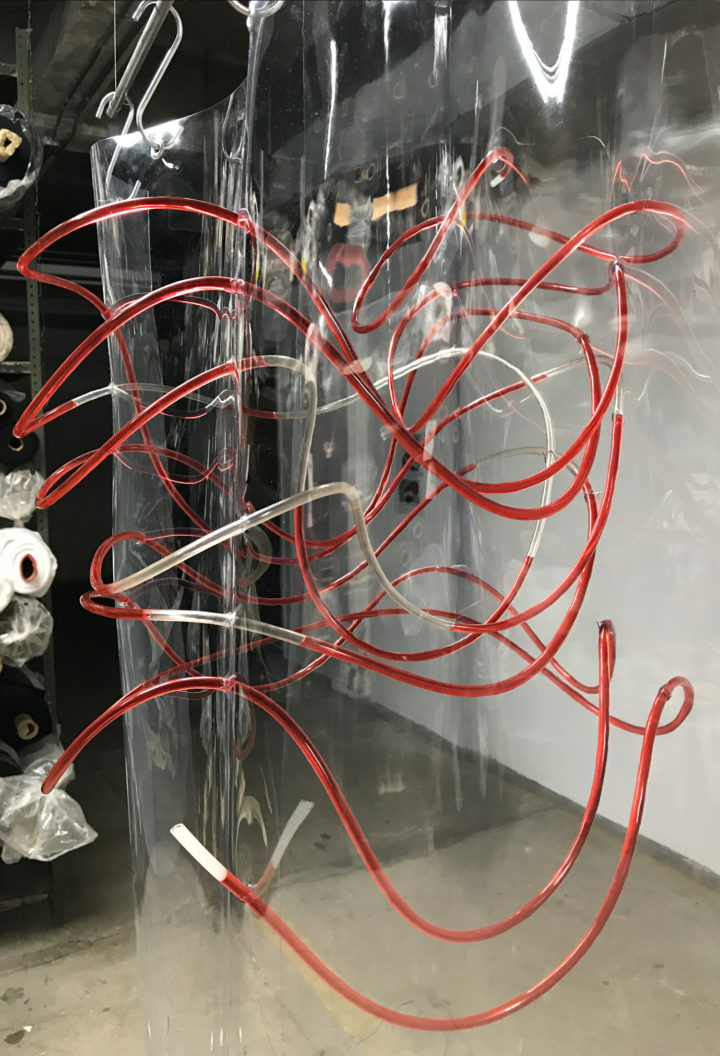

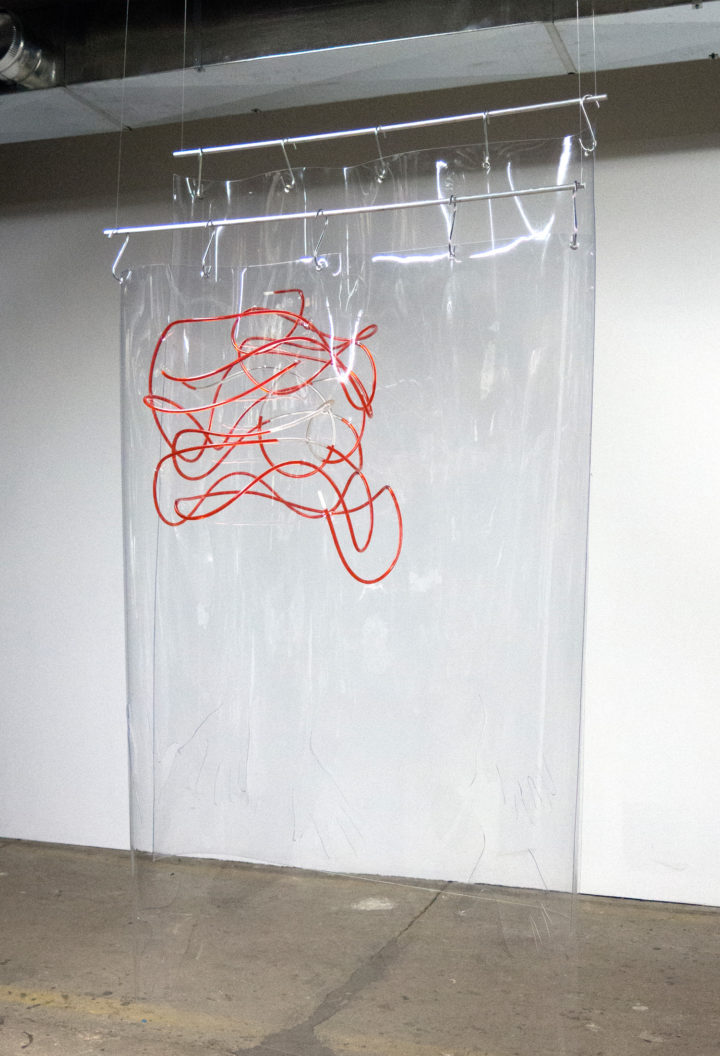

A sensitivity, not quite predicated on fear but on second-nature recognition of the potentially plummeting depths as well as sky-high reaches of human emotion, seems to pique Yavuz’s interest and drive the artist’s thinking through such subtle aspects of the human condition — wrapped up in layered moments and circumstances of relational being, but first and foremost in itself. The four pieces comprising his “Die kleine Philharmonie” series, which take their name from the artist’s favorite bar during a period of studying in Berlin, commonly employ suspended sheets of clear vinyl out of which a limited number of incisions demarcate physically engaged bodily fragments and together colonize a central area of the viewing space. In these, thin plastic tubing is haphazardly woven to entangle two or more figures who appear to be intravenously sharing a steady flow of alcohol. Whether it is Campari, Turkish raki, whiskey, or red wine, the overall forms that result from such linkages are loosened and blurred to a degree of near fusion — with a fittingly caricatured effect.

“I almost always have a little foam on the top at this point.

So I skim the foam with a little spoon…and scarf it down right there in front of my children, my Basset Hound, and my Maker.

I am not ashamed.”

Placed at the far end of a dimly lit aisle created between the large, industrial shelving that permanently exists within the show’s warehouse space, Dinner with Richard (2016), a pair of blue Burts British Hand-Cooked Potato Chip bags, both opened, sit upright on the floor, each lit from the inside with a single battery-powered candle. Like the suspended vinyl works, they face one another and linger in what feels like an anthropomorphized round of conversational catch-up or romantic exchange, almost as if they have escaped from public view — finally at ease in each other’s inanimate company.