A Vogue Idea is a column by Matthew Linde exploring contemporary fashion practice.

The current exhibition at New York’s Museum of Arts and Design (MAD), titled “fashion after Fashion,” promises a bold new definition of critical fashion. As curators Hazel Clark and Ilari Laamanen explain, “Fashion” with a capital F is “an inherent system of short-lived trends, idealized body types, and the presentation of gendered stereotypes, all conveyed with authority through the names of brands…”

The exhibition intends to show that fashion practice can possess intellectual value outside market forces. This hypothesis, which posits fashion criticality as a nascent reality, curiously neglects decades of scholarly and curatorial work dedicated to fashion’s various experiential, social and multidisciplinary relations. Sidestepping this vast history of critical fashion practice and theory, “fashion after Fashion” purports to show “some of the most innovative work being produced” as alternatives to an otherwise oppressive system.

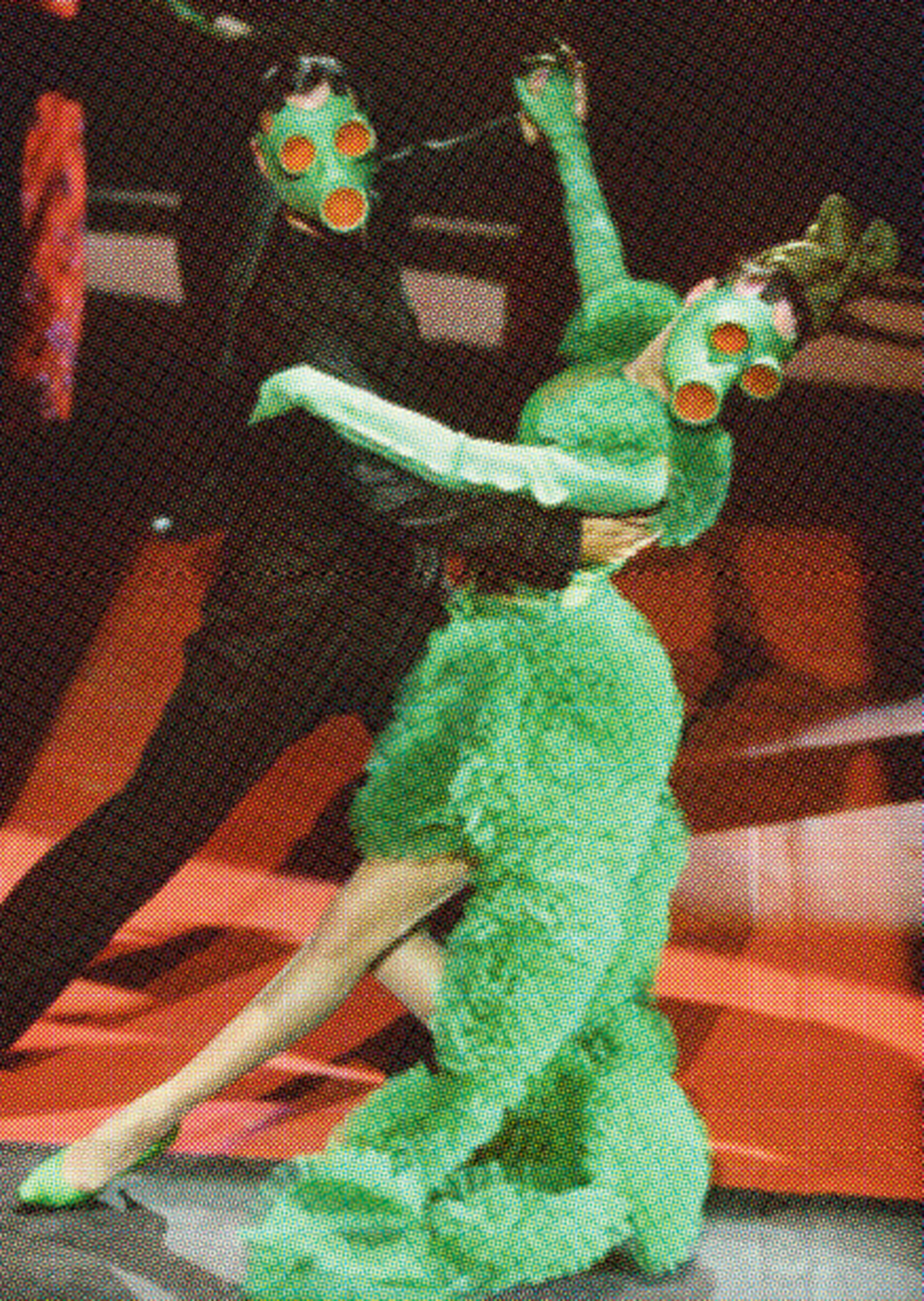

The exhibition brings together six practitioners who deal with the lowercase phenomenon known as “fashion.” SSAW magazine presents a teen bedroom interior completely covered in spreads and campaigns from their past issues. Designer Ryohei Kawanishi creates a faux wholesale showroom with bought garments redolent of Zara pieces; hoping to jam the value-relationship of garment and branding, he has supplanted existing logos and labels with his own. Henrik Vibskov has constructed transparent fabric cubicles with gelatinous Ernesto Neto–style blobs suspended in them. This, we are told, points to “how bodies are enlivened by their garments” and how fashion “references the passage of time.” Lucy Jones crafts ergonomic cross sections of garments that enhance body joint movability for wheelchair users. This suggests fashion’s potential for inclusivity. Sculptural works by the collaborative duo ensæmble expose the innards of garments, highlighting their construction to illuminate our everyday interfaces with clothing. Eckhaus Latta and Alexa Karolinski’s video features downtown New York art characters responding to questions of love and identity while wearing the brand’s clothing. The exhibition claims this demonstrates how fashion can facilitate community.

Unlike the more traditional fashion exhibition approach of isolating a specific time, place, author, style or medium to position a thesis, “fashion After Fashion” denies this curatorial threshold as proof that this new “fashion” practice transcends mere collections and catwalks. While the exhibition format need not remain didactic, the act of selection is also an act of restriction, an indictment made all the more critical for a museum. The question that becomes immediately apparent is: What makes these six key practitioners so illustrative of this new “fashion” frontier? Are the above tactics of imagery, brand jamming, immersive environments, disability design, deconstruction and community truly novel to fashion? Or, have these practitioners canonized once-niche concerns into systemic industry changes?

Within the curators’ vague paradigm shift of “Fashion” vs. “fashion,” profound contradictions are evident. Take for instance the work by SSAW Magazine. The exhibition argues that SSAW is a repudiation of fashion magazines and their proclivity to “present stereotypes of beauty, gender, and age, which they [SSAW] found restrictive and unrepresentative of their interests.” Expecting an insightful shift, I instead discover the magazine almost exclusively depicts tall, youthful, waif-like models, many of them represented by major agencies, wearing the latest in luxury designer fashion. The professionally crafted visuals are virtually indistinguishable from those of mainstream fashion magazines. Fashionably alternative models may appear, but recent campaigns by corporations such as H&M, which present body diversity under the banner of brand identity, question the collusion between representation in the fashion industry and Foucault’s concept of biopolitics. Is this a highly attuned form of institutional critique? Could this be an update of Stéphane Mallarmé’s1874 La Dernière mode, an interventionist project in which the poet, acting as a ficto-critic, published a fashion magazine using a host of pseudonyms to construct a simulation of the discourse? All research points to no. Fashion remains Fashion.

Ultimately functioning as a frivolous curatorial exercise, there is a dearth of any intelligible attempt to expound a theoretical connection between these six practitioners. Yes, they all somehow challenge cultural norms or luxury economies, but this could be described as fashion tout-court. Even high-end “Fashion” designers have been historically known to subvert corporeal and corporate expectations, creating platforms for new gender roles, championing minorities, obfuscating their financial imperative though philanthropy, collaborating with artists and advocating for the individual. Why aren’t they included in the show? This lack of discernment is worrying for a museum exhibition that declaims a manifesto of the “new”; clearly the exhibition does not interrogate the complex marriage of the culture industry and the corporate world. Instead, “fashion after Fashion” offers the nebulous assurance that “fashion” is “more complex, critically informed and socially relevant.”

The fact is that this type of revelatory exhibition of fashion’s expanded field has been mounted countless times: “Biennale di Firenze” (1996), curated by Germano Celant; “Fast Forward: Mode in den Medien” (1999), curated by Ulrike Tschabitzer and Christian Muhr at Künstlerhaus Wien; “Dysfashional” (2007), curated by Luca Marchetti and Emanuele Quinz at the Luxembourg Rotonde; and “The Future of Fashion is Now” (2014), curated by José Teunissen at the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, to name a few.

It has become remarkably evident at this point that fashion’s sensorium is involved in creative processes that transcend market forces (although I would argue that all fashion practice, luxury to niche, remains intrinsically entangled with the market). An exhibition declaring a new fashion must do more than explicate this fact. This is not to say all fashion exhibitions need to adhere to specific themes and cannot tackle fashion as a methodological conundrum. In 1944 Bernard Rudofsky curated “Are Clothes Modern?” at MoMA, a show that infiltrated the broad annals of fashion, challenging its genetic makeup, through Veblen and other anthropologists, as a grotesque semiology of class politics. In 2005, “Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back,” curated by Judith Clark at the V&A Museum, addressed fashion as analogous to Benjamin’s concept of the tiger’s leap, as the dialectical image where past and present cyclically meet. Unlike “fashion after Fashion,” these exhibitions used pointed propositions to curatorially challenge our understanding of the fashion system.