A glass of absinthe, such as those as seen in two of Willa Nasatir’s rephotographed photos on display in “Joshing the Watershed” at Del Vaz Projects, can evoke a certain nostalgia for a particular era in the life of a Western artist, roughly spanning the period from Impressionism to the Lost Generation of the ’20s and ’30s. The exhibition space itself, an unassuming two-bedroom apartment in a dense part of Westside, can then suggest the domestic settings of the artists’ salons of Mallarmé or Stein. Yet perhaps a closer comparison could be made between the academic salons of the 19th century and our present-day art fairs. The challenge of navigating hundreds of canvases hung closely together has something in common with the bewilderment provoked by mazes of gallery booths, and our more democratic incarnation remains beholden to our schools of art. All this only highlights the contrast between the dying gasp of an idea of art as an imitation of life on one end of the timeline and a situation in which art claims its legitimacy as an imitation of art on the other.

Nasatir’s work is especially keyed in to this conflict. The anxiety latent in the formal process of damaging or altering the surface of a photograph and photographing the results recalls the crisis provoked by the medium’s emergence well over a century ago, when painting began to emphasize individual perception over mimesis and so approach the sort of self-referentiality that has become the hallmark of modern art. This quality being now thoroughly fetishized, the work seems imbued with a life of its own, entering a sort of society as a debutante, only to go to die in a domestic grave, the trophy of some collector.

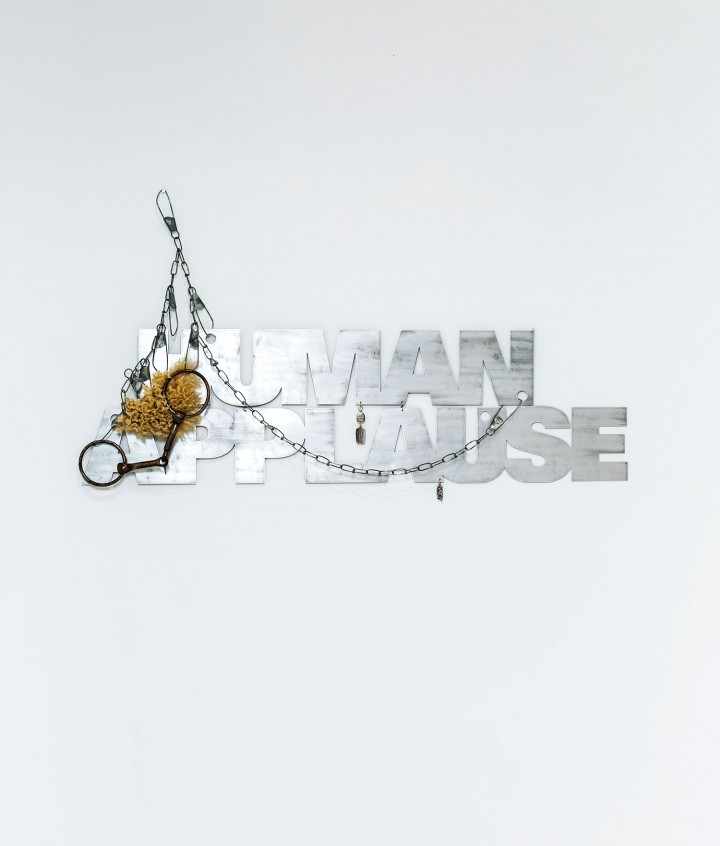

Here, in an apartment that may as well stand in for this twilit space, a carnivalesque atmosphere takes hold, playing Jessica Williams’s bittersweet, painterly portraits against the chrome, chains and key-ring charms of Dena Yago’s Human Applause, while Math Bass’s tortoise stages a lightly comedic encounter with Sam Davis’s anthropomorphized mic-stand readymade. In the show’s other room, a bedroom, the intimacy of the space invites a disarmingly empathetic relationship with Adrian Gilliland’s camp male playing-card nudes, and Dwyer Kilcollin’s vases, produced through what could be called an artisanal version of 3-D printing, address questions relating to technology, the human hand and failure. These are rooms that seem hardly fit to host a person’s watershed moments, yet are much like many in which people come into the world and leave it.