Timothée Chaillou: For your show “Where the Lions Are” at the Kunsthalle Basel in 2009, you were inspired by “the idea of a kind of momentary or fleeting occupation of light”. You installed one of the chandeliers that were hanging over the negotiation table in the Majestic Hotel in Paris (upon which the peace agreements for the Ivory Coast, Kosovo, and Vietnam were signed), under a skylight “where the sun, moving around it and shining through it, would rip it from history and time itself.” At the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, you are exhibiting the three chandeliers in a state of transit: one on a hanging rail, one in a wooden box, one in separated pieces on the floor. What were the reasons for these displays? Why did you choose to dismantle one of the chandeliers to fill a room plunged into darkness?

Danh Vo: I like to try different methods of installing a work each time it is shown, if it’s possible, and if it makes sense. I really liked the way the chandelier looked at the Musée d’Art Moderne, spread out on the floor and lit up. The other chandeliers were borrowed from individuals and institutions and came with the support systems used in the exhibition. There was less flexibility with those, but the concept behind the exhibition was to have them come together again in Paris, after they had travelled and been exhibited in different museums around the world; the idea was not necessarily to play with their components.

TC: For the Venice Biennale, you have imported the skeleton of an entire 200-year-old Catholic church from Thai Binh Province, Vietnam. Do you think of this piece as a “refugee”?

DV: I don’t really like the word “refugee” because it conjures up specific images we all have of someone in a crisis, and it doesn’t allow a person to have a complicated identity. It implies a subjugated position as we have come to understand the word through the media. Likewise, I wouldn’t put such a heavy label on the church. It was demolished and the wood was up for sale. Usually the wood is purchased to create houses; it was going to be repurposed anyway so why not repurpose it in its original form for an exhibition? In addition, the church was not “fleeing” Vietnam. In a way, you could see it travelling to Italy as a kind of “homecoming” for a Catholic structure. Yet, if you look at its style, it is clearly not Italian.

This project actually began with a trip I took where I retraced Caravaggio’s route from Napoli to Malta during the late period of his work. On this journey, in Syracuse, Sicily, I discovered the place where he painted The Burial of Santa Lucia in 1608; this was the most beautiful experience because painting as well as the actual burial, the grave, was gone. When Constantine moved the capital to Istanbul (Constantinople), he took Santa Lucia’s bones with him. Then, when the fourth crusade defeated Constantinople, they took all the relics back, and now Venice has the bones. Syracuse attempted to get the bones back when Italy was unified as a nation, but instead they were given all these Murano chandeliers. That was what triggered the installation in Venice, thinking about how things move, how history moves things…

TC: “Cultural Boys” (2007) are photographs taken by Joseph Carrier in Saigon in the 1960s. He photographed young men in the streets who are often holding hands or ambiguously engage with each other. Do you think of Joe’s photographs as fantasized self-portraits of you (like Jack Pierson’s “Self-portraits”)?

DV: I have definitely referred to them this way before, but in reality it’s more complicated and should be seen instead as a set of relationships, which might be crushed by this reading: the relationship between Joe and the men he photographed, between me and those men I never met yet feel a connection to—not simply as Vietnamese but through the “homosexual veil” that Joe cast onto them when he took the images, and my relationship with Joe and the authorship (and power) I have assumed in exhibiting the images. All these details are equally important and should be held in tension with one another.

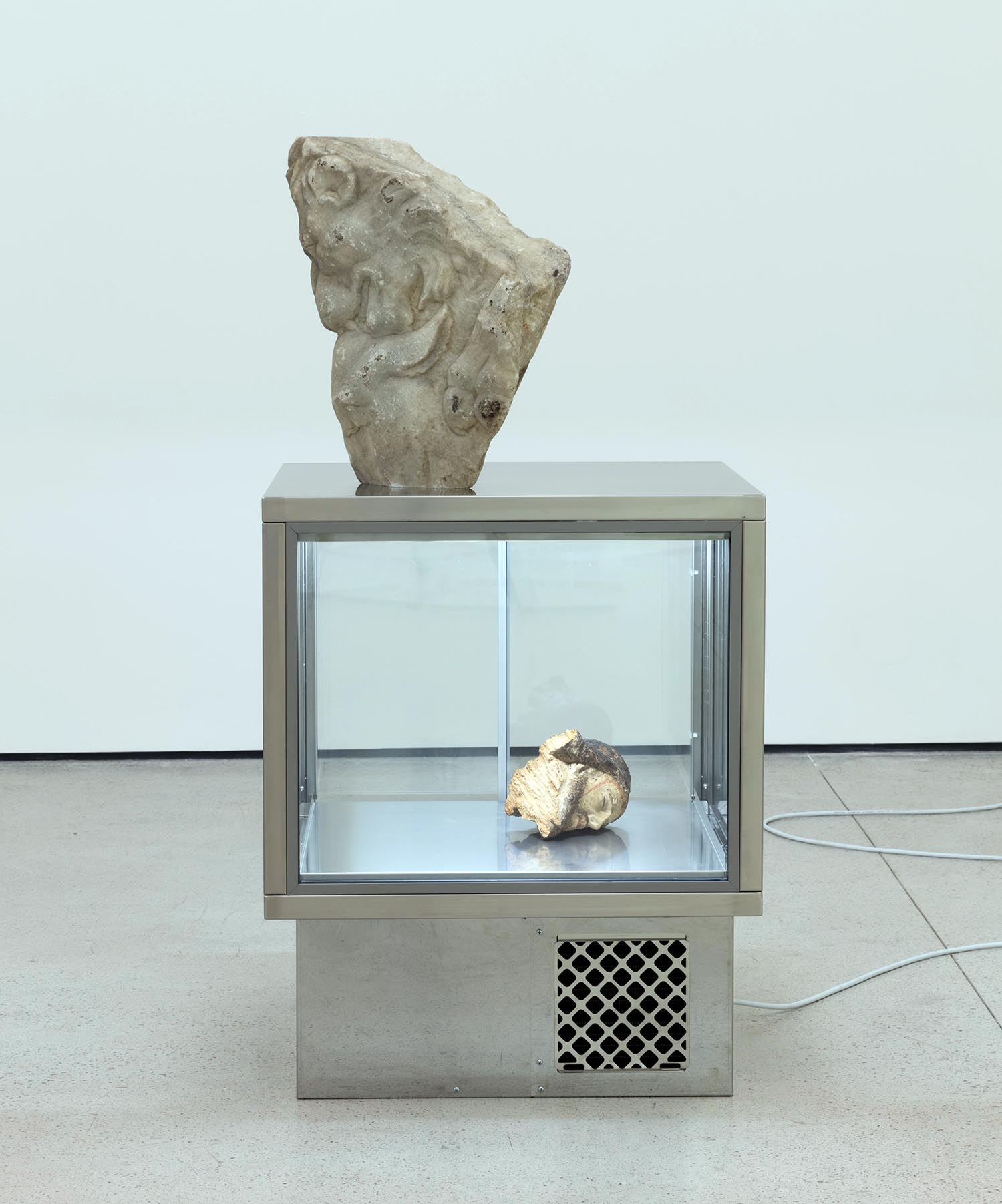

TC: What led you to use vitrines as a conceptual and structural framing device? Were you interested by the idea of inaccessibility and virginity?

DV: These are devices that have existed for hundreds of years in both a consumerist and museological realm. Why should I create something new when these designs have “worked” to showcase precious things for so long? These frames should not be taken for granted, they aren’t simply accessories, they have a history and a function of their own. It’s interesting, I hadn’t thought about the vitrines in relation to “virginity” because the objects I put in them are not new, they are crumpled cardboard boxes or an old ring for example… I don’t think the vitrines make the works inaccessible because that is the device that makes them available to the public. Because there is this glass, you can look it up close. It suggests a preciousness to something that might otherwise not be seen that way.

TC: Everyone has their own little arrangement of objects, somewhere right up front or stacked in a niche. Why is it that we have to express ourselves through objects by creating a mise en scène?

DV: I’m not sure I can comment on why everyone does this. However, I do think that we collect things that we desire, because what we desire tells us something about who we are. I guess that’s why I like to shift and change my arrangements from one exhibition to another. These things should never be fixed or totally resolved. Desire is a complicated thing.

TC: At the MAMVP you are showing belongings of Robert S. McNamara: “Lot 100. Six Small Middle-Eastern Antiquities” (2013), a photograph from Ansel Adams (Lot 89. Adams, Ansel, 2013), “Lot 1. Annotated Carbon Copy of McNamara’s Letter of Condition of Accepting Position of the Secretary of Defense” (2013), “Lot 20. Two Kennedy Administration Cabinet Room Chairs” (2013), “Lot 39. A Group of 4 Presidential Signing Pens” (2013) and a lacquered box (Lot 11. Vietnam Photo Album, 1962, 2013). For what reasons was it important for you to show his belongings as traces that recall a political history? How did you manage not to drift into nostalgia?

DV: These sorts of items never end up in public auction; it was purely by chance that I was able to get my hands on these objects because they are normally donated directly to Presidential libraries. When Sotheby’s put them up for sale, they produced the most beautiful catalogue with well-researched entries about the items and beautiful illustrations. I wanted to preserve their work, in part, by keeping the lot numbers and descriptions as the titles of the works, and working from these groupings to make new works. I suppose I tried to avoid nostalgia by not being sentimental with the objects. If something needed to be ripped apart, like the cabinet room chairs, then I ripped them apart. I didn’t give the objects new names or identities; they were simply transported into an art context.

TC: Your father’s story of survival after the Vietnam War served as inspiration for a collaborative work with Tobias Rehberger titled “Go Mo Ni Ma Da” (2004) – which is also the title of your show at the Musée d’Art Moderne. After the fall of Saigon, over 20,000 Vietnamese citizens were evacuated to an island called Phu Qouc, where they lived under horrendous post war conditions. After four years, your family decided to risk their lives and escape by building a massive vessel that could carry over 100 refugees away from Vietnam and, ideally, to America. Your father had to find a way to cover production costs, find materials, create the design and bribe local officials so they would look the other way as the refugees escaped. Your father built his boat and the refugees were able to sail out to sea. Your journey was interrupted by a large tanker headed for Denmark which forced your boat to anchor. Your family has been living in Copenhagen ever since. Are you using this story as a mythology (like Beuys’ accident)? What are the connections between this piece and your show in Paris?

DV: I think that whether or not I used my biography in my work, my work would be read in relation to my personal history, so I anticipated this when I wove it into my work. Beuys created his story and then made work out of it, that is one difference between our practices.The project with Tobias Rehberger did not go as I had planned but I liked this title very much… it comes from a New York Times article I read in the travel section about a journalist who is greeted every morning in Vietnam with “Go Mo Ni Ma Da”—“Good morning, Madam”. So I wanted to have a second chance to use the title and think about what it means.

TC: Do you think of your appropriated objects as “talkative”?

DV: If they are talkative, I hope they aren’t saying anything too specific. I think we always bring a lot to a work when we look at art and what we bring to the work engages us in a conversation with the objects in front of us. In that way, I suppose they are talkative. But I try as hard as possible not to give them “lines.”

TC: When someone calls you a “conceptual artist” what does it mean to you?

DV: It makes sense if you have to give me a title to see my work and mode of production within the legacy of conceptual art because I am not someone who sits in a studio and produces new things. I take things that already exist in the world and alter them—not just objects but systems and ideas.

TC: Do you think of all your works as love letters?

DV: Inasmuch as the work consists of things I desire, they are love letters in a sense, yes, but they aren’t addressed to anyone in particular.