Since his earliest contributions to the Arte Povera movement in the 1960s, Emilio Prini (b. 1943 in Italy; lives in Rome) has refined an art practice sometimes described as “ungraspable,” “deceptive” and “cryptic.” It is a practice grounded in pure ideas, without regard for conventional aesthetic criteria — a practice that isolates the act of “art making” from those of creating and producing, thus demanding art’s true potential as a critical tool outside the constraints of capitalism. Given the total saturation of images, objects and experiences provided by the art industry today, Prini’s declaration, “I create nothing, if possible,” and his persistent revisions and recontextualizations of his own past works, suggest new strategies for a dematerialized conception of art that defies the limits of commodification. The three texts that follow — by Luca Lo Pinto, Pierre Bal Blanc and Alfredo Aceto — survey Prini’s production, delving into the ideas that characterize his oeuvre, namely those of nonproductivity, standardization and void.

Luca Lo Pinto on the ineffability of Emilio Prini’s art

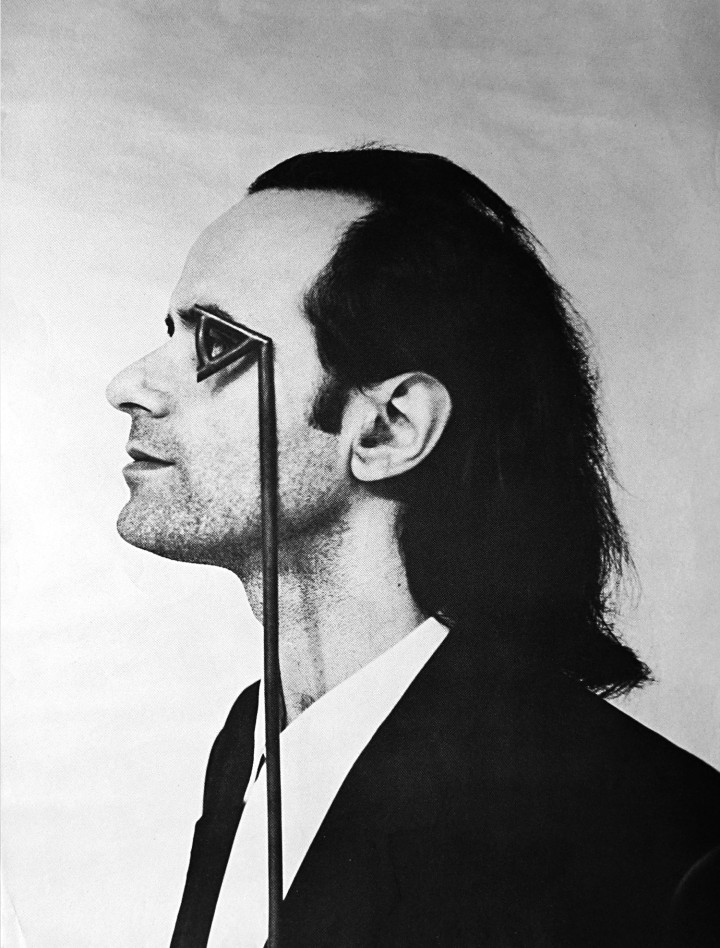

Emilio Prini is one of the most complex and enigmatic figures of his time. He is the Giorgione of the twenty-first century. Like the great Venetian artist, his appearance in the world of art was astounding. He made his debut in 1967, contributing to the birth of one of the most influential art movements of the second half of the twentieth century, Arte Povera. Germano Celant invited him to participate in the exhibition “Arte Povera–Im Spazio” at Galleria La Bertesca, in Genoa, although his art had never been shown before. Until 1974 he participated in the most significant exhibitions of the period (“Op Losse Schroeven,” Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 1969; “When Attitudes Become Form,” Kunsthalle Bern, 1969; “Konzeption/Conception,” Stadtisches Museum, Leverkusen, 1969; “Information,” MoMA, New York, 1970; “Contemporanea,” Villa Borghese, Rome, 1973), but subsequently he reduced his exhibitions to a minimum. Documentation of his work is scarce. There is no catalogue raisonné or even an interview. Prini is a precious but evasive asset. A grandiose artist who never adapted to the codes of the art system, forcing it to adapt to him with a tenacity that is unparalleled. Prini is truly a warrior of Time and History.

Like Caravaggio, he works without a preliminary sketch, but with the manic intensity of Poussin. Nothing is casual. The title, the caption, the lettering, the placement, the architecture, the light, the color of the space where the work is placed, the size and type of paper upon which the work is reproduced in the catalogue. Each element has a value because it exists, consequently nothing can be considered irrelevant. Everything contributes to creating an equilibrium.

Like poetry, Prini’s art cannot be explained. It is ineffable. He introduced a limited number of ideas and works which that he continued and still continues to develop, re-elaborate and modify, remodelling them like a living material that has not yet become fixed. At times this takes the form of minimal gestures, such as revising a date, changing a title, isolating a detail of an image, photographing a finished work or rebuilding it. Consequently, the authorship, originality and uniqueness of the work are all questioned. It is a method of working comparable to that of a composer who incessantly rewrites the same score with subtle variations, well aware that even a simple repetition implicates the idea of a difference. Prini’s works are artist’s proofs that aspire to never become finalized — they are works in which, as Piero Manzoni claimed, time is the only dimension.

Prini was very prolific between the years of 1967 and 1972, though most of the works he conceived he would not exhibit until later (those of partial disappearance), while others would remain hypotheses on paper (those of total disappearance).

There were notes, instructions, formulas and nursery rhymes (some published in Pallone magazine, some in the book Arte Povera and some on sheets of notebook paper at his Galleria La Bertesca solo exhibition in 1968) that expressed central concepts such as the idea of the void, of duration, of space/image relationships and the notion of variability within a given absolute.

Some annotations were pressed into a sheet of lead that weighed as much as his arm. Some of these phrases included: “I read Alice in Wonderland”; “ I’ve laid a trap for Alice”; “I walked a long way on the road. My body was photographed at five fixed points”; “I walked up a hilly street”; “I daubed the pavement with brown aniline. It wore off”; “I obtained a movement”; “Another hypothesis on the void.”

It was a retrospective in advance. Prini wrote his own History before he lived it. A corollary that condensed the works of a lifetime. A fascinating scientific experiment in which various elements appear and disappear in different states, changing, cancelling and recreating themselves in a continuous flow. A good example is Fermacarte [Paperweight] (1968): a stacked group of black-and-white photographs (portraying the artist in “typical everyday actions” such as jumping, walking, going down stairs, etc.) with a piece of lead on top as a paperweight. The weight of the lead matched his own weight. A conceptual piece, but with a pictorial quality that recalled Boccioni and Bacon. After being exhibited at Galleria La Bertesca, the work was proposed again in many variants: with a different combination of photographs; with total or partial coverage of the silhouette with the lead; as a photograph of the same.

In another note, Prini referred to “the idea of a plaster cast as the dimension of what is not represented” and further observed that “the size of the body is proportional to all/the sizes/the distances.” In Passi [Steps] (1967) he reproduced his own steps with geometric wooden elements. Other explorations of the idea of volume and void include an occasion when he signed the white floor of an empty room in a gallery with a blue felt-tipped marker. He cited Klein (the blue) and Manzoni (the signature) together to surpass them. In 2007, he presented an empty room in Rome. If Klein made the void into a work of art, Prini exhibited it and accepted it for what it was. A void is a physical condition. It is not art. It is authentic and cannot be copied. In 1971, in the catalogue of the “Arte Povera” exhibition at Kunstverein München, he left the pages dedicated to him blank. Four years later, Michael Asher did the opposite by gluing in two blank pages as his contribution to Vision magazine.

Projects for possible films to shoot also appear among the written forms of communication. In the Bolaffi Arte ’70 catalogue, on one of the two pages dedicated to him, he published an image of two photos that reproduced the nape of a person along with this caption: “Shoot a close-up of the nape and the open world for one hour, following the direction of the wind as it changes. Add a soundtrack about energy. Add a fixed subtitle. Shoot different napes in different wind conditions.”

In another catalogue, he published the project for an eight-minute TV film with the following indications:

Shoot a sunny day darkened by the close-up finger and the surrounding open void, following the rotation of the earth/of the sun/Move the camera generally/Shoot 12 hours to show in four minutes/Invisibility of the duration/Light thickness/Eclipse of the source/Shadow on the eye of the man.

Shoot a night the moon obscured by the close-up finger and the surrounding open void, following the rotation of the earth/of the moon/of the sun/Move the camera/Shoot 12 hours to show in four minutes/Invisibility of the duration/Light thickness/Eclipse of the source and the reflecter/Shadow on the eye of the man.

Prini adds nothing, he subtracts on the scale of Michelangelo. He works with a limited, almost invisible, perfectly calibrated intent that completely eliminates the “actions of an artist.”

In 1970, his contribution to the “Processi di pensiero visualizzati” [Visualized thought processes] exhibition at the Kunstmuseum Luzern consisted of a telegram reading, “Confermo partecipazione mostra” [Confirm participation in the exhibition].

In the same year, in a special issue of the British magazine Studio International, edited by Seth Siegelaub, the artist published an exchange of telegrams between himself, Jean Christophe Ammann (curator of the exhibition in Lucerne), Kynaston McShine (curator of MoMA’s “Information” exhibition) and Tucci Russo (at the time an assistant at Gian Enzo Sperone’s gallery), presenting it as a comedy for four actors. The telegrams sent by Prini again declaimed “Confermo partecipazione mostra”.

All that remains of a book project entitled Confermazione Partecipazione Edizione [Confirmation Participation Edition], which was to be edited by Germano Celant and published by Gian Enzo Sperone in 1971 (it was never realized), is a draft for the cover.

Many of Prini’s works defy perception. They suggest a vision of reality that is simultaneously analytical and highly imaginative, obtaining the greatest result with the least effort.

In 1975, for example, he produced an extraordinarily lifelike portrait of Napoleon using only the O and comma keys of a typewriter. Earlier, he had made hundreds of drawings using an Olivetti 22 typewriter and standard A4 sheets of paper. These small masterpieces appear to be the outcome of a sensual combination of mathematical formulas, architectural designs, visual poetry and musical scores.

Such means of working and living resisted methods of historicization and the tools of interpretation; they also made commercialization and distribution of his output very difficult.

A path suspended between the laws of physics and the singularity of vision, between the standard and the variable, in which the work is conceived as an empirical verification, and aesthetics are developed through the relations of a series of data extracted from reality.

In September 2009, invited to participate in an international conference on Documenta organized by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev at Castello di Rivoli (Turin), Prini sent his friend Anna Butticci to represent him, giving her the task of presenting a reading of all the information contained in the letter of invitation (including the letterhead, sender, recipient, address, postal code, etc.). It was an even more radical form of tautology than that adopted by Joseph Kosuth. In fact, Prini pushes such gestures so far that they are difficult to categorize as artwork, performance or lecture. If Kosuth reflected on the definition of an artistic object, Prini redefined the role of art and the artist in an almost alchemical fashion.

Years ago he declared, “I have no program, I grope my way, I see no trace of the birth of Art (nor of Tragedy) because the C.S. is not the fruit of pure human work (because I did not make the chair, the table, the sheet of paper, the pen I use to write). I create nothing, if possible.”

His fascination with the concept of “standard” is thus hardly surprising. Standard (1967) is a 6.5 meter bar of aluminum profile for variable placement, the configuration being dependent on the space in which it is situated. In 1967, it was placed in Galleria La Bertesca to be photographed. In 1973, it was installed in Galleria Toselli. A conventional tool of measurement that contradicts itself because it changes depending on the space.

The artist’s attitude to consider every work open-ended is evident in every exhibition or catalogue in which he has participated, including the most recent. In the “Arte Povera 2011” exhibition curated by Germano Celant across several Italian institutions, Prini was one of the few Arte Povera participants to present a previously unexhibited work. Both at Castello di Rivoli (Turin) and at MAMbo in Bologna, he displayed the exhibition catalogue of the event itself, placed on the floor, opened to the pages about himself; the public was invited to browse through the publication and wear it out. The title of this work is Arte Povera 2011, Electa, Milan 2011, pp. 554–557. Again in this case, it was a variant of an earlier project proposed to curator Rolf Wedewer for the exhibition “Konzeption/Conception” in 1969. As he had written in a letter, “For the exhibition, open the catalogue to the pages of the project/put it on a transparent base of the right height for reading and the right dimension for the catalogue/allow people to leaf through it entirely.”

In this case, the artifact being worn out is a book, but on other occasions there have been other technological devices such as a camera (Magnete [Magnet], 1968) and a tape recorder (STANDARD, 1969). Continuous use of these objects leads to their self-destruction. The mechanical repetition of every gesture (including artistic), image, word or object leads to disappearance, to annulment. The work ethic produces its negation

At the present, in a world dominated by the hyperproduction and consumption of images and objects, Prini’s artistic and intellectual position, based on continuously interrogating the need for production, has thus become indispensible.

Prini is still on the move, erasing his points of passage on the map, meanwhile presenting himself like a mocking clown hidden in the shadow of art. The mask to hide another self, both identical and alien.

Lisa Ponti, daughter of the great Giò, who shared the adventures of many artists, once said to me regarding Emilio: “When I met him, above all I was amazed by his severity and absolutism. The point is that he must be and not be at the same time. Another would have said, ‘I want to be in a visible position.’ He, on the other hand, wanted to be almost invisible but definitely present.”

(Translated from Italian by Nuovo Traduttore Letterario)

Luca Lo Pinto is a curator at Kunsthalle Wien.

Pierre Bal Blanc on Emilio Prini’s notion of standard

In a declaration included in the only monograph on Emilio Prini ever produced, Fermi in Dogana (Musée d’Art Moderne in Strasbourg, 1995, on the occasion of the artist’s only institutional survey exhibition), the artist confessed to not having a program, and in this way was carrying on the experience of radical dispossession started in 1967. On the eve of the events of 1968, which would swing Europe into the spirit of capitalism, leading to the living out of a new version of the “cité par projets,” Prini, for his part, had never had a project other than not having one. By introducing the notion of “standard” into art in 1969, the artist undertook the task of exhausting various recording, conservation and data-reading devices and systems with their own consumption. A tape recorder records the production of its own sound until the tape breaks (STANDARD, 1969). A camera is used continuously until its mechanism becomes obsolete (Magnete [Magnet], 1968). The obsessive utilitarianism of American consumer society appears like a symptom, revealed in the title of Prini’s work L’U.S.A. USA [The U.S.A. Use] (1969). By associating the acronym of the United States of America and the verb “to use” in Italian, the artist displays the manic-depressive tendency that was making its way to Europe by way of the new free-market society developed by those once colonized. This manner of wearing out and exhausting his work, in the sense of plunging it into the abyss or damaging its aura, is repeated by Prini in a variety of conceptual and material registers. For example, there is an “ultralogical” accumulation on the top floor of an art center (Frankfurter Kunstverein), one that threatens the building accommodating the exhibition because of the weight of the standard chipboard sheets placed there are on the verge of the exceeding load-bearing limit of the floor (Castata Ultralogica, 2000).

“Fermi in dogana” was subtitled, by the artist himself: “A collection of works from 1967 to 1995 chosen by my cat.” These coded words can summon different interpretative hypotheses, one of which might be defined as a position against the very principle of interpretation — an act of resistance against an antiquated place of customs clearance that implies the interpretation of goods in terms of commercial value. But to better understand this, we can revisit Susan Sontag’s Against Interpretation, published during the same period in which Prini’s work first emerged:

Today is such a time, when the project of interpretation is largely reactionary, stifling. Like the fumes of the automobile and of heavy industry which befoul the urban atmosphere, the effusion of interpretations of art today poisons our sensibilities. In a culture whose already classical dilemma is the hypertrophy of the intellect at the expense of energy and sensual capability, interpretation is the revenge of the intellect upon art. Even more. It is the revenge of the intellect upon the world. To interpret is to impoverish, to deplete the world in order to set up a shadow world of “meanings.” It is to turn the world into this world. (“This world”! As if there were any other.)

The selection criteria of Prini’s cat might include the possibility of getting away from an anthropomorphic viewpoint, and focusing instead on the world in order to show that other living beings and inert objects are also looking back at us. “Uno standard meraviglioso” [A marvelous standard], to be presented later this year at the contemporary art center in Geneva, city of banks and preservation of capital, is an area of one hundred primary structures measuring one meter by two, made with polystyrene sheets which, like elongated bodies, fill an exhibition space. This synthetic material, used as an insulating product to improve our comfort, fills the space where people move about, with the vertical silhouettes of visitors providing some material form, somewhat in the manner of the car fumes referred to by Sontag, taking revenge on man and his sensibility atrophied by domesticated matters.

Only the marvelous, which is to say not that which is here now, but that which is remembered with nostalgia, or that which is ideally dreamed of, still makes it possible to impose the exercise of the standard (is not all advertising based on these last two tropes?). “I don’t create, if possible,” said Prini, affirming by inscription an attentiveness to the world and its sensual present. In flight from a gleaming fantasy, he calls, like Susan Sontag, for a somber erotic art.

(Translated from French by Simon Pleasance)

Pierre Bal Blanc is a curator of documenta 14.

Alfredo Aceto on Emilio Prini’s “La Pimpa Il Vuoto”

I was fifteen when I first encountered the work of Emilio Prini in the Galleria Giorgio Persano in Turin. I went into the gallery somewhat listlessly but I recall that in the short corridor from the entryway to the exhibition rooms I caught a glimpse of a few images of the animated film La Pimpa [by Italian cartoonist Francesco Tullio Altan], which awakened some strange sensations in me. I perceived that I was approaching something that, considering my young age, would be an experience that was hard to talk about.

The great white walls of the gallery were almost completely covered with steel panels. Prints of Altan’s cartoons were attached to each of them. The colors of the amiable little red-spotted dog had disappeared, and with them the spirit and the poetry of the cartoons, suggesting however that the visitor might discover another more complex poetry.

The appearance of the steel supports was very cold and industrial, unexpected and not connected with the images. La Pimpa (the little dog) and Armando (his owner), whom I knew well, were present in each vignette, but here they had lost control of their dialogue. The sense of narrative had also disappeared, even though the balloons took up most of the space of the images. It was something like when snakes shed their skin, leaving behind a sort of empty and transparent reproduction of themselves.

Although the gallery space was full, when I left I felt a strange sensation of emptiness. I had the impression that those enlarged vignettes were there only to avoid disappointing the people who had climbed the stairs to reach the gallery. But that was not the case. With this action, Prini had filled the empty gallery with tangible elements that, paradoxically, left it even more empty. The task of defining that unbridgeable gap was left to the visitor, an action that could be completed only in the absolute presence of something tangible.

What was soon evident to me was that the work of Prini was not there where I sought it, in the image, but rather was to be identified in the spaces between one panel and another, which formed a kind of suspense: the impossibility of a logical thread and thus of a progression.

Years later, when some began to confuse what the French call le fond de la forme [the content of the form] with regard to digital art, I realized that in “La Pimpa Il Vuoto” [La Pimpa the Void] Prini had anticipated what emerged many years later. The two characters of the vignettes, victims of their own non-dialogues, were winking at the difficulties of communication that arose with the arrival of new media. Today, looking back, those hermetic exchanges, without resolution but still omnipresent, seem to almost move away from the look of a cartoon and to now resemble a chat.

The void that Prini created is capable of expansion by conquering new territories. In this case, for example, the subtraction implemented at the exhibition went on to contaminate the text that Hans-Ulrich Obrist wrote about this body of work. Prini first censored some phrases in Obrist’s text and then continued the subtraction by penning some corrections in the published version of the text. The resulting text is a manifesto that, together with the La Pimpa panels, constitutes a single installation titled “Installazione alla Galleria Persano, Torino 2008” [Installation at the Persano Gallery, Turin 2008]. In this way, the void that Prini generated at the beginning contaminated all phases of production, mediation and enjoyment of the work.

The exhibition at Giorgio Persano’s gallery seriously shook me up. Perhaps it was the first time that my boyhood status had been seriously challenged. An important moment. I thought of Emilio Prini as the caterpillar in Alice in Wonderland, a creature who made silence his strength and wisdom, and who assisted others by giving them their own tools for taking on the world. Perhaps I automatically associate him with Carroll’s character because of the poetry with which Prini refuses to fulfill what the world expects of artists. His resistance is not based on a calculation, but on the preservation and avoidance of what he himself calls the “Prini brand.”

Each exhibition and each gesture of the artist are an invention — thus never a derivation — that delivers the artist to a place of transition and discovery. I believe that these inventions of his are akin to silences amid the noise caused by all the other works of art that saturate our perception. I recall a conference that Romeo Castellucci held at the ECAL in Lausanne, during which he spoke of how the saturation of images today leaves us in the middle of an absolute desert, a place where it is impossible to believe in the force of representation any longer.

Conventions are often turned upside-down in Prini’s actions. By redefining the context, the artist stimulates our interest in an apparently simple, accidental, underlying reality: a standard linked, in the first place, to the small scale of the boring day-to-day that flows within the narrow alleys of the mind, and subsequently, to the fairytale poetry of a disturbing fiction. In Prini’s exhibitions, time always gets the better of space. This is a very unusual attitude in the world of art; we are used to having time regulate space rather than a space that hosts time.

If Emilio Prini’s work has influenced the artists who have followed him most persistently, outside of Italy his name is not familiar. This ambiguity between the potential of his work and the scarce visibility of his radical implications fascinates me considerably. Often I have looked among artists my age for any sign of his legacy. Even if less radical and more inclined to compromise, many young artists take us back to a world in which the object produced is less important than a precise and interested attitude with regard to its contemporaneity. Some, like Cameron Rowland, communicate with a poetic inspiration not too distant from Prini, in which the economy of art and the authorship of the object are again subjects of interest. Others, like Achraf Touloub, just film a fragment of their own leather jackets while they are walking down a street with their backs to the audience — always fleeing but always nearby, incapable of evading the image.

(Translated from Italian by Nuovo Traduttore Letterario)

Alfredo Aceto is an artist. He lives between Geneva and Paris.