Patrick Steffen: I’ve wanted to organize this conversation since 2011, when Rita Gonzalez curated the show “Asco: Elite of the Obscure, A Retrospective, 1972–1987” in the same space where we are right now. And there was this sequence from Mur Murs (1980) projected on the wall…

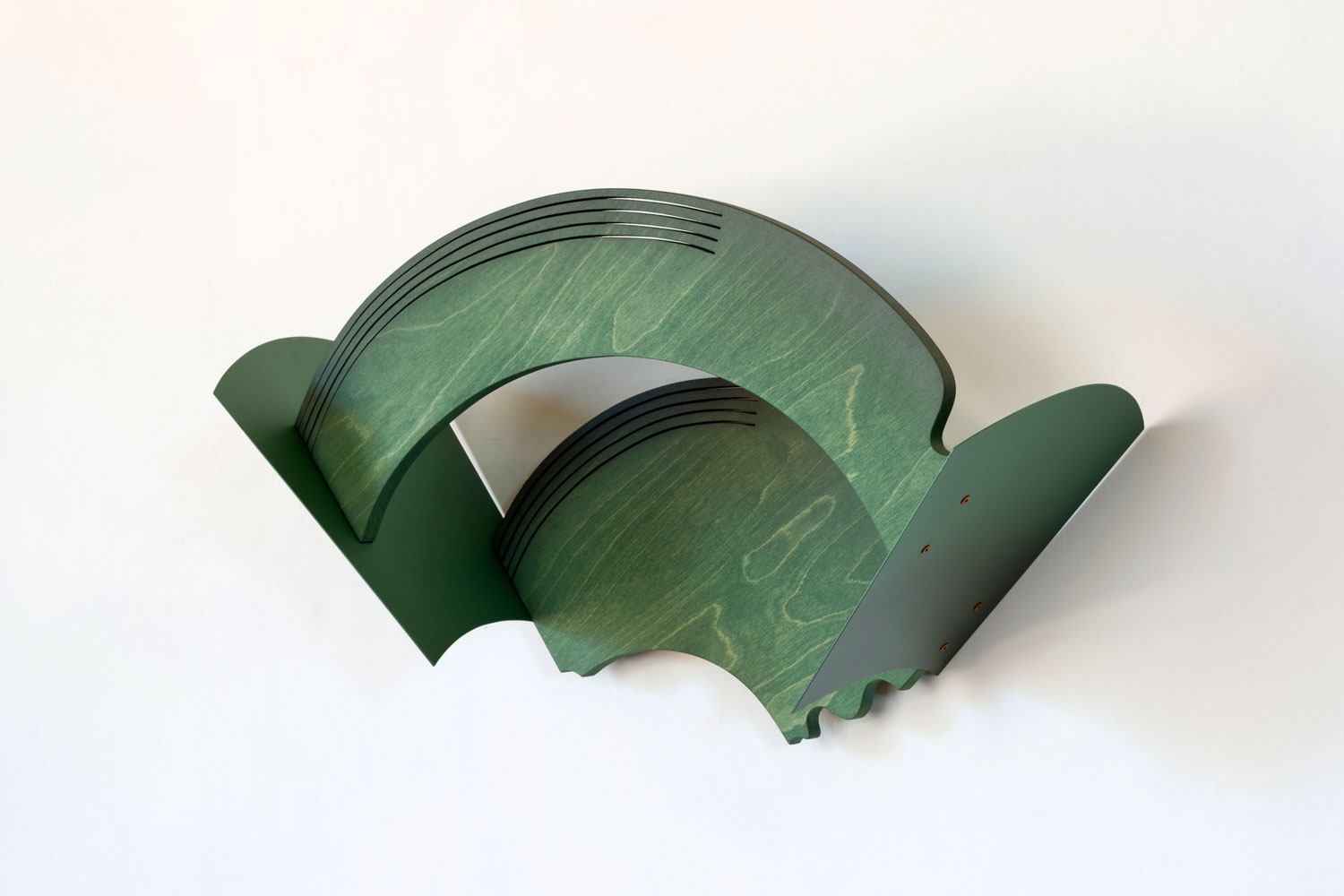

Agnès Varda: I filmed the murals in a time when nobody cared about this subject; it was 1979–1980. I went to East LA and I had two insider contacts, a young mother and a priest. I admired what these people were doing on the walls. At that time most of the people coming to East LA were exploiting the murals as a simple background for fashion photos, for advertising. So I told them: “I’m just enjoying what you do, and I want to film that, because it’s interesting.” I became totally at ease in that area, even when everybody said, “Don’t go there, it’s dangerous!”

Rita Gonzalez: What impressed me about that documentary, and in general about the time you spent in California, is that you had an incredible eye for detail and reality. So often we have seen cliché images of Los Angeles: theestablishing shots, the Hollywood sign, the beach, the surfers. But you had a completely different take: the oil rigs, the murals, the long boulevards. These things fascinated you, and your images of the city gave a more accurate rendering of the city.

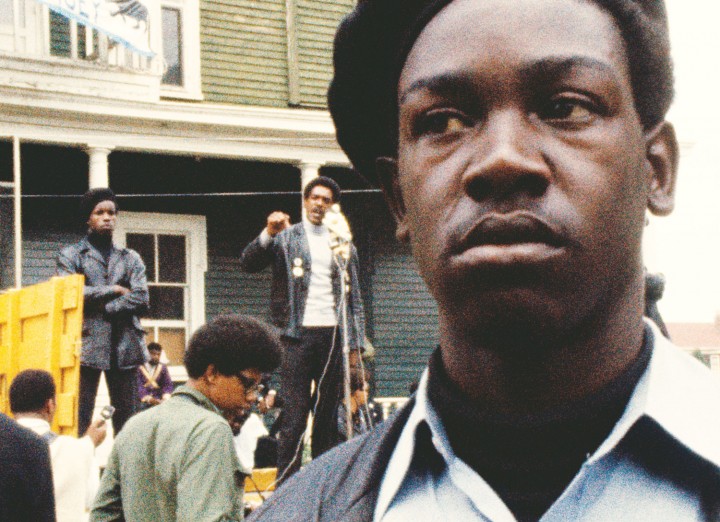

AV: We were French, we were excited about the American way of life, we had rented a little house with a little pool. But we had our own way of looking at it, and I especially remember the dream-like feeling that we experienced when driving in the city. I first came to LA from 1967 to 1970. I did the film Uncle Yanco in Sausalito and Black Panthers (1968) in Oakland. I got involved in the hippie community. On another side, we were well received — Jacques Demy and me — as representatives of the Nouvelle Vague, and were invited everywhere, like cultural puppets. We even met Jennifer Jones, Gregory Peck, Mae West… I was also very excited at that time because I discovered for the first time the theories of Marshall McLuhan, and Women’s Studies at UCLA. These things didn’t exist in France.

PS: Since then you’ve come back to LA regularly.

AV: Very often. For instance for The Beaches of Agnès (2008), or for the series Agnès de ci de là Varda (2011), in which I travel around the world. In my position as a filmmaker I grab reality and just turn it into a shape. Recently I observed other visions of Los Angeles, some new murals, and so many murals that disappeared. That’s how you understand it’s a different time; there are some new ones, but some have just faded and vanished. That’s the beauty of cinema; you can capture things that don’t last.

RG: In Documenteur (1980), the way that the murals and Venice were used is an interesting companion to Mur Murs. In Mur Murs you’re interested in the walls speaking and the artists giving their voice and vision through mural painting. You play with that, even in the title. In Documenteur the characters are walking through the space,the murals are in the backdrop, and the murals play off of their feelings and their emotions.

AV: In Mur Murs I’m serving the subject, which is the mural. When you do a fiction, you decide. And in Documenteur, I picked from Los Angeles some documentary images as the representation of something that the main character (a woman) cannot say. I don’t know if that’s happened to you: sometimes you feel something, it doesn’t have a name in your mind, then you see an object, an image, and it tells you what you feel. For Documenteur I really used this device. I used all these kinds of impressions that I saw. Real characters from real life. I projected myself into the reality of these people that I met by chance.

RG: Sometimes you also used situations that you happened to catch instantly. In Lions Love (…and Lies) (1969) there’s this scene where you go to Venice Beach and there’s a big gathering of people. Then the police come in and you get that intensity, that real moment through your camera.

AV: This kind of scene places the fiction in real time. For instance, while working on Documenteur, I really wanted to feel that pressure, that sense that people come to California with a desire to be successful. And then you see Venice Beach, and I would say it is like the end, with a lot of disillusionment. I was even using the pier as the ultimate West. Through what I could see I was telling emotions. Having made fictions and documentaries, I go from one to the other with ease.

PS: In Lions Love (…and Lies) there are these words on the screen: “Should art imitate, exaggerate or deform reality?” That question from 1968 is still valid today and you could say that this is a statement for your entire career.

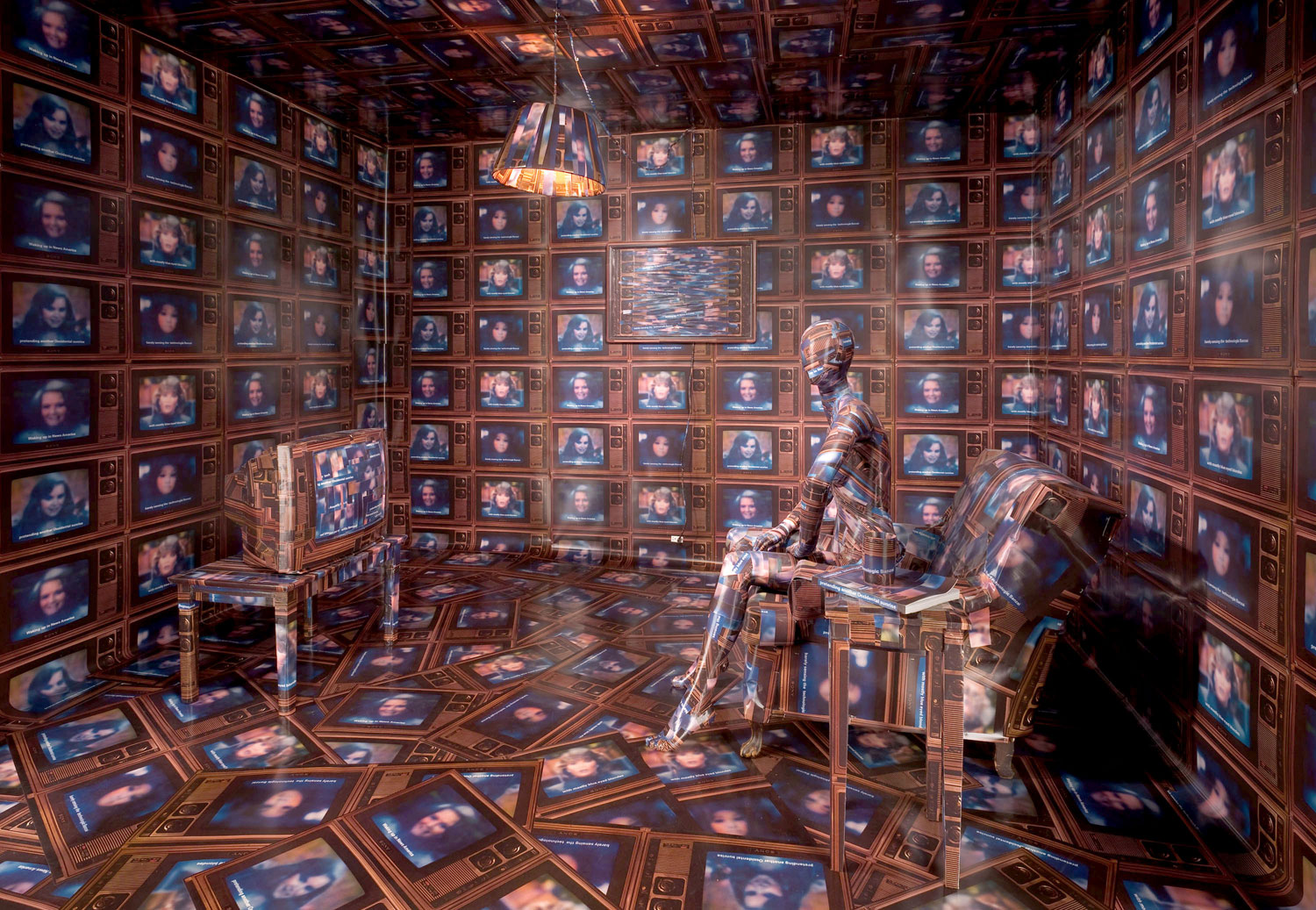

AV: Sometimes I try to describe, sometimes imitate, sometimes reinvent. I like to propose something and then give the viewer the right to be himself, to make up his own Brechtian distancing. Take, for instance, this shack made of reels where we are currently. It’s so exciting! Have you ever been inside a film? Inside the director’s heart!

PS: This is my first time.

AV: This is my basic material. It is dematerialized as a film that can be projected. It becomes the material itself of the film. I wonder: How does it feel for you to be in the middle of the reels?

PS: I feel like Pinocchio in the whale.

AV: Interesting, because the whale is one of my favorite images. A whole stomach is a shack. Once someone asked me: “Why make a shack?” I said, “Don’t you remember when you were a kid, making shacks everywhere?” As soon as the shack was up and had a door that we keep open, I said to Rita: “Thanks for inviting me to do this. I feel so happy to propose surprising impressions. Nothing violent or striking, just simple strange impressions that a film is a body, a whale, a shack with walls of film, reels of cinema.

PS: And since we are looking at these reels, I wonder how it was for you to embrace the digital revolution and work with a digital hand-held camera, starting from The Gleaners and I (2000).

AV: I started to use small digital cameras at the right time. This documentary had a very social subject for which I had to approach people. I couldn’t see myself with a professional crew. And I knew I could go alone. I had my camera in my hand, and I could speak to the people I was interested in and say, “Look, I’m doing this because I’m trying to understand what’s happening to you.” And I asked them to understand that I needed them.

RG: Is this shack also a memorial or monument to the passage from celluloid film to digital video?

AV: This is something that happens with age. I don’t see my past films like a collection of films. It is like a body, something that is alive but outside their representation in the theater.

RG: I also think about creating a refuge space, and that is also consistent with your filmography. There’s a notion of creating a refuge within the structure. It’s like you create a space for reflection.

AV: We’re living in reality, but our mind, everybody’s mind, is always projecting ideas, allegories, feelings, memories. And I’m so old… I have a bad memory, but a lot comes up anyway — a lot! And time is another subject that I love to work with. In Cleo from 5 to 7 (1961) I worked with a precise time as a material, ninety minutes as a material, and now it’s a film that has become material. And I can use them outside of their meaning and context. It’s like a recycling process for me — recycling things I’ve done that still have meaning. It’s a creative process too — not just an older lady remembering her past works. It’s like discovering another life, like these shrunken potatoes that we see in The Gleaners and I, simple potatoes, totally wrinkled, ready to be thrown out, not eatable. And then they grow again; they have little roots. That touches me so much. It’s like an allegory of myself in a way. It touches me because life is so strong. I find this to be such an interesting theme. And so they even made fun of me. They called me “Madame Patate,” and I love it. Another theme in The Gleaners and I was about society formatting everything, and whoever is out of the format is out and has no value. Again, these wretched potatoes, they are not to be sold because they are not in the format. Many people suffer because they are out of the format.

RG: After The Gleaners and I you did The Gleaners and I: Two Years Later, revisiting the main characters. And with all of these restoration projects you’ve been making more bonus videos, for instance for Daguerréotypes (1975). The way in which you’re revisiting the original location and the people that you shot, the situations, is fascinating. You are activating new encounters. It’s not nostalgia.

AV: It’s about revisiting. Reviving. Again, it is what I said about the potatoes. Regenerating. Redoing something, endlessly. Is it possible to revive something that is supposedly part of my history, my past filmography? I think it’s possible. What interests me is to capture some of the natural vital strength.