Donatien Grau: Was your first encounter with art or with artists?

Shaun Caley Regen: Probably artists of some kind, whether they were poets or writers or musicians. Literature was really very important in my parents’ household and I always read from a very early age. There were always discussions around books and politics. When I went to Barnard and Columbia, I mainly studied literature, writing and art history. Along with literature, I studied critical theory in Paris. As a writer, writing was difficult for me! I think I was a little bit too hard on myself. Writers need to have a very specific ego to keep writing: they must have this kind of incredible belief and purpose that they keep pushing forward. I find that artists are much the same way.

DG: How did you first connect with the art world?

SCR: When I studied in Paris from 1981–83, I would go to the library at the Centre Pompidou, as well as the other incredible libraries in the city. I was in college in uptown Manhattan, and the museums in New York were fantastic. I would spend a lot of time at the Met and MoMA. I saw my first Whitney Biennial. Later the East Village was starting. It was all quite exciting. I think one of the first openings I walked into was at Mary Boone in SoHo. It was a Jean-Michel Basquiat opening. Here was this beautiful artist in this white gauze kind of outfit. I think it was Comme des Garçons or something. I just thought the opening was the most glamorous thing I had ever seen in my life. I was about 23, probably. After graduation, I moved downtown and started writing for Flash Art and seeing all the gallery shows. For me, it was really fun writing reviews fresh out of school, and it was a continuation of an intellectual exercise in a way. You could see every continuous gallery show, throughout the year, which was relatively easy to do back then.

DG: Then you moved back to Paris to work with George Condo.

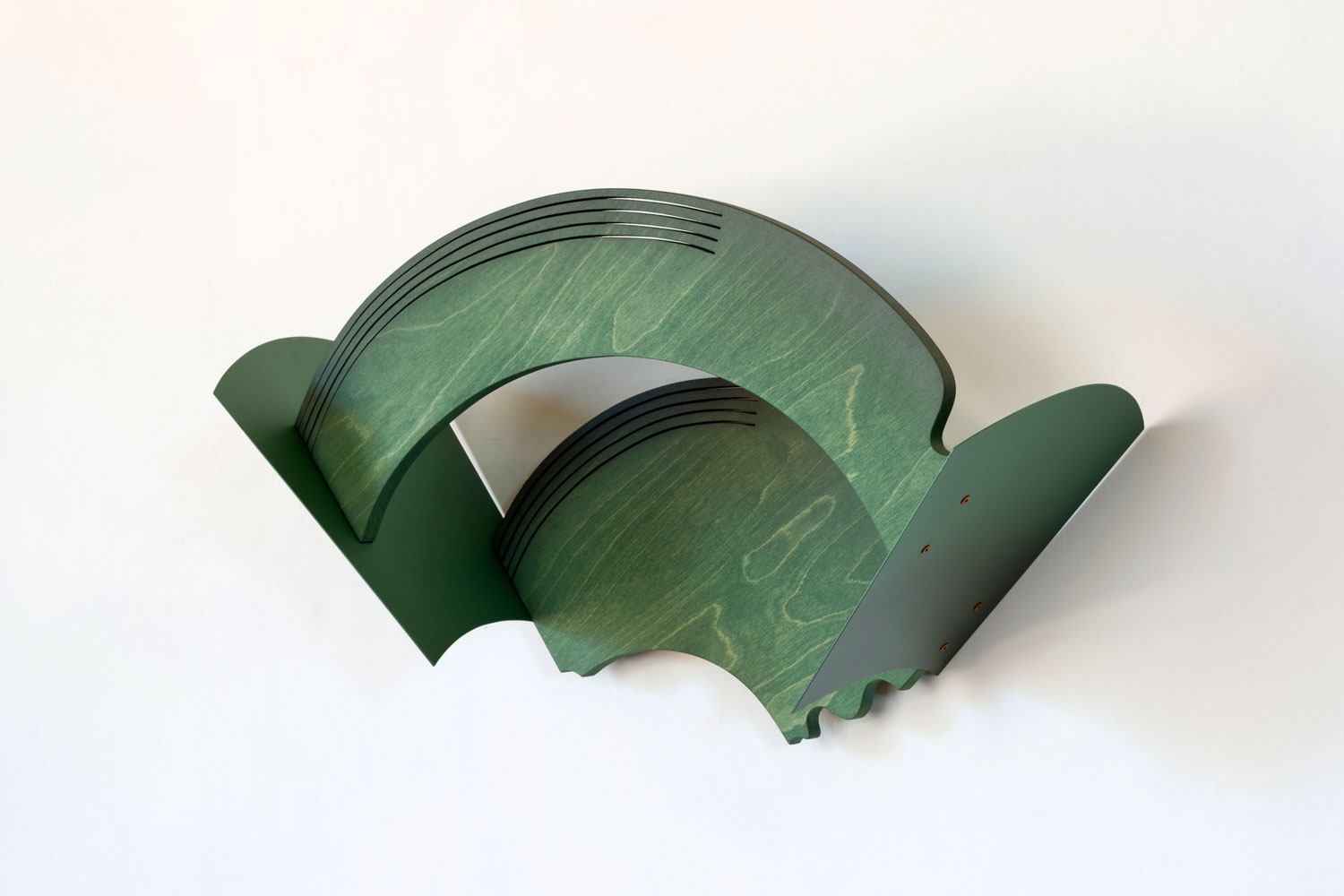

SCR: I had written a review of his work. Someone wanted to introduce us, and he was looking for an assistant. “Can you move to Paris tomorrow?” And I was like, “Sure!” I went there and worked as his day assistant. We would go and buy paints or furniture. We’d pick up money from Bruno Bischofberger over at the bank. We’d have lunch. We’d watch Jimi Hendrix videos and The Shining many times. He’s fantastic and funny. The more I knew about artists, the more exciting the practice of making art was to me. After Paris, I moved back to New York. Flash Art hired me in Milan and I spent a year there, then I moved to Los Angeles. I think the first two people that I met and really clicked with were Stuart Regen and Liz Larner. Liz was one of the first artists that we decided to represent, along with Lawrence Weiner, who was our first show.

DG: You studied critical theory, worked as an artist assistant and as a managing editor of a magazine. Then you were part of a gallery. How did it all happen? Was it organic, or actually rather difficult?

SCR: It was not natural for me at the beginning. Sales were very slow in the early ’90s. And I tended to over-talk things or over-intellectualize them, and then I’d watch art consultants come in and emphatically say, “Just buy it, it’s FABulous!” and they would make a sale. I was like, “Really?” I would say it took me a while to figure it out.

DG: First of all, the gallery was called Stuart Regen Gallery. Why did it change, in 1993, to Regen Projects?

SCR: It was such a bad time to open. We opened in December of ’89 and the economy collapsed. We sold little or nothing for our first two years. We basically ran out of money. We found a smaller space that we could hopefully afford and thought we would do projects around the city. The first one we did was Richard Prince’s First House in ’93. We did a project with Lawrence Weiner at the Central Market downtown in ’95, and screened some of Matthew Barney’s Cremaster films in various venues. In the end the artists seemed to prefer to use the small space as a gallery. There was so much inexpensive and affordable real estate that “pop-up” shows made a lot of sense in the early ’90s. I’m glad that we started that way because it means something. You don’t just expect what everyone is experiencing now. You know something quite different.

DG: How did all the artists you worked with come to LA?

SCR: Well, I think we were lucky because I had been at Flash Art in Milan, so I had a lot of information come across my desk. Stuart had worked for Rudolf Zwirner in Cologne and was very close to a number of German artists, as well as the artists he grew up with being Barbara Gladstone’s son. When the market bottomed out and we left our first space, we moved to the smaller space and our programming became more free. Of course, we were very lucky that he and I had international relationships and many strong friendships in New York. I would say that there were a lot of factors that came together. Artists were always excited about coming to LA. Often it was a hard place to work because maybe there weren’t so many collectors. We were also a burgeoning gallery. We hadn’t really developed artists of our own yet, and that came a little bit later. But artists always liked to come here.

DG: Regen Projects always had a very intense relationship with the city. How do you define it?

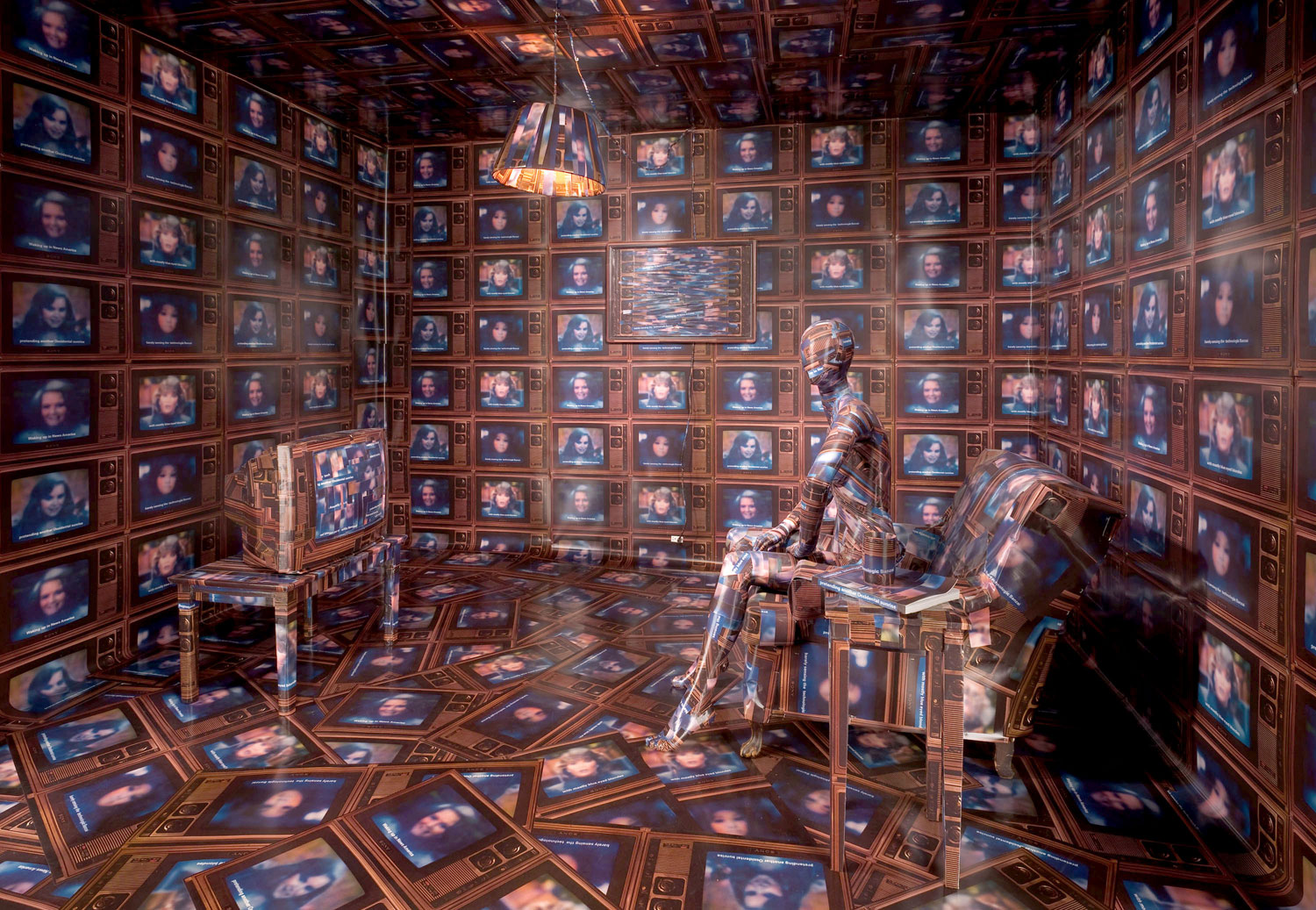

SCR: Well, one of the things I always thought here was: what can you add to the city that the museums aren’t doing, or that someone else isn’t doing? What is not being seen here? For example, John Bock and Jonathan Meese were two German artists that were very visible in Europe and not in the States, or certainly not on the West Coast. They seemed interesting because of the history of performance art on the West Coast, and we ended up working with John Bock. John’s first show was packed. Paul McCarthy and Jason Rhoades attended. We had the tiny gallery and it was jammed with all these people. Sometimes you want to put something in front of your audience that you feel like they need to see or should be aware of.

Glenn Ligon’s first show at the gallery was in ’04. He was an artist I had long admired from Whitney Biennials, and I had visited his studio in the mid ’90s when Thelma Golden curated the “Black Male” show. When I saw his work in Okwui Enwezor’s “Documenta XI” (2002) I was reminded how brilliant and important it was. Since he wasn’t showing here at the time, again, that seemed something very important to show in the context of the gallery and the community. Then, partly because the institutions were so great here, particularly MOCA in the golden years, everyone just kept raising their game. Also, sometimes it’s nice to introduce something contrary to what you see being done around you.

DG: There is this whole idea that LA is a city with great artists and great museums, and that the galleries do not necessarily always have a very good time. Do you agree with that?

SCR: It used to be that a lot of people in LA would go to New York to buy art. That probably still happens sometimes although a very strong collector base is growing here, and often the reverse can happen. And there are so many great artists here. The things that changed all of our lives were the Internet and the proliferation of art fairs.

In Los Angeles we have had the pleasure to work with so many great artists over the years who have honed their singular and substantive vision on the West Coast. From Raymond Pettibon, Lari Pittman, Liz Larner, Toba Khedoori, Catherine Opie, James Welling, Andrea Zittel, Doug Aitken, and more recently Elliott Hundley, Walead Beshty, and Ryan Trecartin and Lizzie Fitch. All of these artists have made such enormous contributions. But Los Angeles has been a great art production city for decades. And accompanying that have been tremendous museums, galleries and art schools, too.