From Flash Art International No. 156 January-February 1991

Jutta Koether: We ought to talk about the work you’ve produced in the last couple of years, meaning 1988 and 1989, which is the period you spent in Spain. Certain changes seem to have taken place in your work. You’ve done many things, but almost exclusively outside Germany: you’ve been trying to decentralize and now I have the feeling that I’ve lost my overview of Kippenberger.

Martin Kippenberger: Let me sum it all up. I moved to Madrid and I’ve since had shows at Hetzler in Cologne, Metro Pictures in New York and Luhring Augustine Hetzler in Los Angeles, all on the same theme, but developed in various ways.

JK: This sort of triple exhibition is a tactic

that artists, especially Jeff Koons, have frequently adopted as a way of exhibiting their work, but for you it was the first time. What led you to make the experiment with such a way of showing art?

MK: Life wasn’t so wonderful, so something more wonderful had to be made to happen. I’m kitsch, so art might just as well leave me alone.

JK: What were the final results of such an experience?

MK: Well, it was my first experience of a tour, which seemed to fit in with my new kind of life, always on the move to somewhere else. In any case, it’s somewhat exhausting. And the amount of planning and preparation required is unbelievable. It’s the sort of situation where you start to develop entirely new ways of screening things. Your head insists on that. Your head as a kind of appendage to a splintered body.

JK: What did America “make” out of Kippenberger? You were in Los Angeles at the end of 1989 and the beginning of 1990. What was the bottom line?

MK: It was a learning experience in what, for once, was a different way. Americans could be said to have found their real identity in film and music, but that’s only how it used to be since now that identity has again been lost, or simply sold off to the Japanese. So to distract themselves, and maybe as a way to search out some “newer” identity, they go off and buy the Jaguar Corporation, which is an English firm that really makes no sense in America. Even in terms of design, it’s totally out of synch with America. Everything’s reduced to a game of mirrors where real tradition has found itself abandoned. So that’s why I too needed to spend some time in Los Angeles, to check all of that out.

While I was there, I could do whatever I wanted to. Like getting to know the language better. But you’re still an outsider. Then there’s the whole dull ritual of “knowing your way around.” For example, there is no decent spaghetti. They just don’t exist. They’re called spaghettini by the people who “know their way around.” Hamburgers are guzzled one after the other, but the price for that is that there is no spaghetti Bolognese. People want to live healthily, and one just doesn’t eat ground meat!

JK: How did people in Los Angeles react to the piece with the BMW and the “Sozialpasta” ship on top of it?

MK: My feeling is that exhibitions are always overrated and my experience in Los Angeles just confirmed it. You can change the world for yourself, but exhibitions are totally superfluous. Unless you’ve got a family you have to feed. Art is nothing like film. You can’t at all think of it as big business; it’s always a kind of ‘one-man business.’

JK: You mean it still has the structure of a retail market? In spite of all the mass production and blockbuster shows?

MK: Absolutely. For the artist, the art business means first of all that you play the role of a decoy. As time goes on, people can begin to take a true interest in art, but that’s when they’ve had a good look at thirty thousand shows and they’ve developed a little love for art and a bit of sensitivity, and then finally they can really get something out of it. Yet still we’ve got the idea that people should have the chance to look at those thirty thousand shows! Maybe never coming away with anything.

JK: Is this a new way you’ve found of looking at things, or was it always there, waiting for a clear formulation– after more than fifteen years of making and thinking art?

MK: It’s not new at all. It’s only a question of keeping a clear grip on something that was always true: the fact that the exhibition, as far as the art and the artists are concerned, always has the status of a “running gag.” That’s already a very good question, the question as to why a person should move at all. For me, I always find myself on the move, for example when I visit a new city, with the intention of going some place where I may get stuck. I still haven’t managed, but I keep on trying.

JK: What that leads to is a true proper “circulatory system” for objects where art and meaning are produced; and then art and meaning are destroyed, and then you start from scratch all over again.

MK: Exactly. Which means that we’ve finally discovered a deeper meaning in art (laughs). Los Angeles is a city that doesn’t have a center. So as a European you have to concentrate only on a piece of it. I myself picked the part that was closest at hand, which was Venice, and I ended up by buying a partnership in an Italian restaurant. Simply once again to have the possibility of leaving my traces and droppings behind. So now in Venice, California, there’s an Italian restaurant where you can sit undisturbed and eat spaghetti Bolognese!

You look at all the art people in Los Angeles, and they’re either curators or sponsors. And the function of the artist? Thousands of reasons are always being found for decorating a wall. But real intensity is something you hardly find. An artist doesn’t have to be old, he/she doesn’t have to be new. An artist has to be good. I mean when you walk through a show some of the pictures are good and some of them are bad. Then there’s possible controversy. And not, please, where everything is equally good. Lüpertz and Knoebel are always perfect. That’s what’s so awful. When everything is good, none of it counts. God, in the beginning, wanted that a bit differently. Both good and bad were supposed to exist. But contrasts and dialectic have disappeared in art.

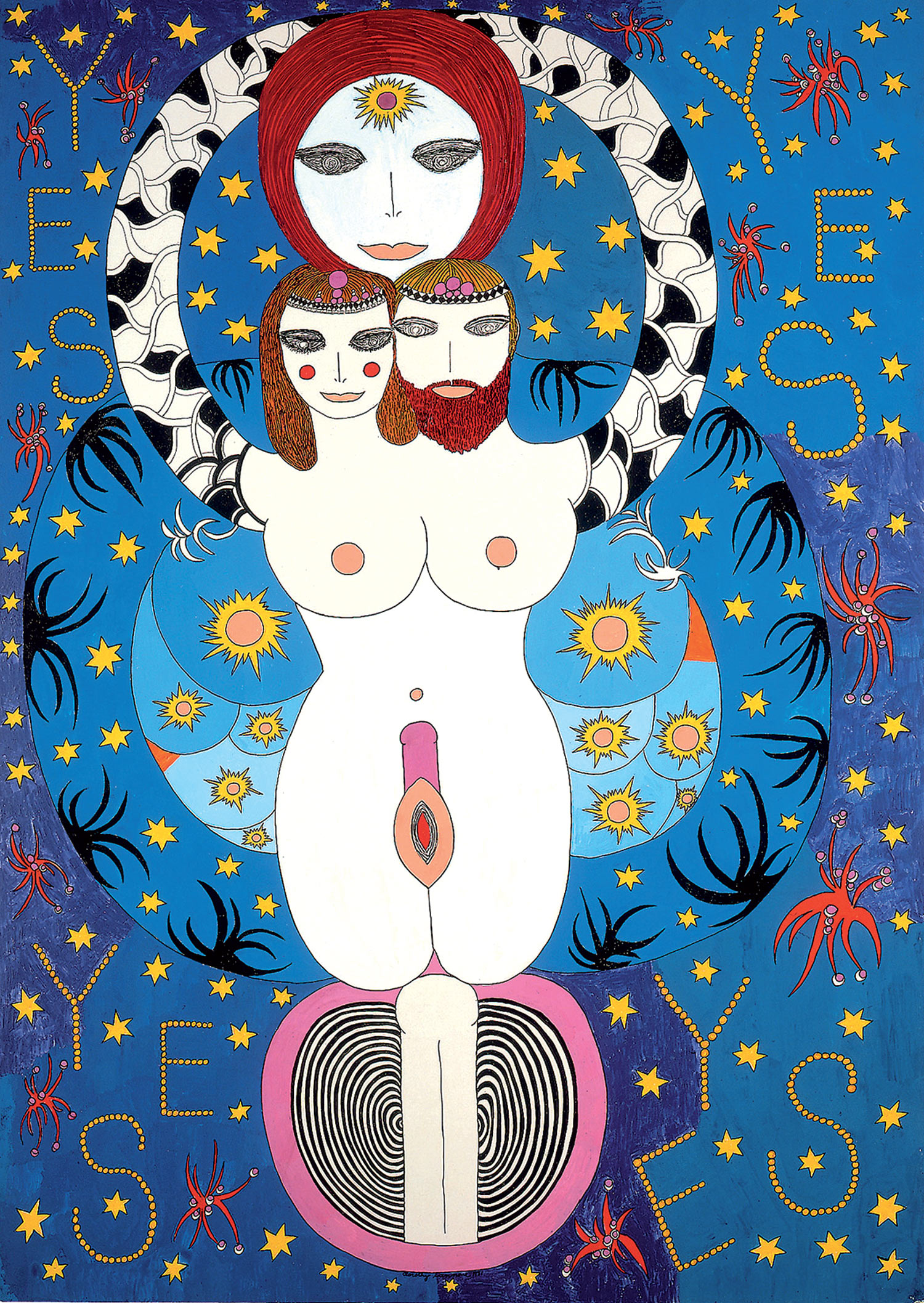

JK: Do you see yourself on the side of what you’ve described as “the new woman’s art” or on the side of the artists who specifically make art about the observation, distribution and communication of art? Are you yourself a good representative of the things you’d like to support?

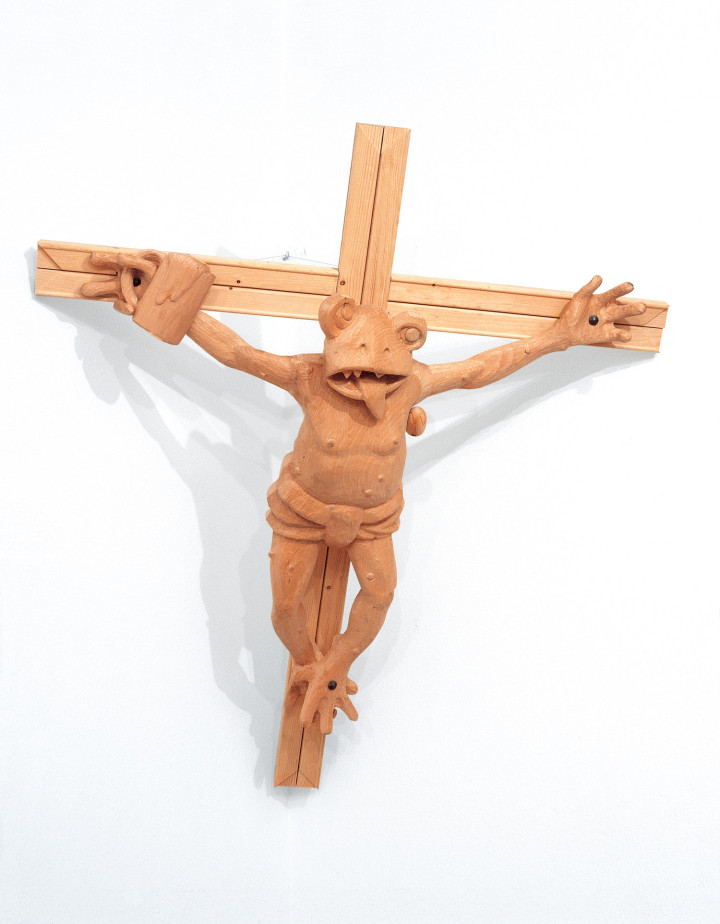

MK: Yes, I am also a woman. That’s quite true! My intentions with the whole of humanity are really quite good. Women so often have a way of holding themselves back as a way of promoting somebody else as the front-runner. That’s a tendency I see in myself as well. I’m not a “real” painter, nor a “real” sculptor, I only look at all that from the outside and sometimes try my hand at it, trying to add my own particular spice. I’m not interested in provoking people, but only in trying to be consoling.

Assuming roles is something that simply won’t work for me, since I don’t have a style. None at all. My style is where you see the individual and where a personality is communicated through actions, decisions, single objects and facts, where the whole draws together to form a history. In any case, people always look at art with hindsight, and always from the outside, hardly ever in the moment it first appears. I’d say usually about twenty years afterward. People come along later and can say what the work and the artist were really all about. What people will say about me then, or maybe not say, will be the only thing that finally counts. Whether or not I contributed to spreading a good mood. What I’m working on is for people to be able to say that Kippenberger had this really good mood.

JK: And what about the people you support and protect, the people whose work you buy, like for instance Merlin Carpenter, or Michael Krebber?

MK: You just get addicted. And in a situation where so little is happening, people like that are easy to notice. You can tell right away just from how they walk. A kind of radiance! And when they’re artists to boot — and people like that usually turn out to be artists — you simply say to yourself, well, if they can say that better than I can, and if they’ve got their stuff or their special talent under good control, then I’m not about to get stuck with the work around my neck and they also have something to offer, and so I’m happy to help them develop. In buying other people’s work, I can take another good look at everything all over again, including myself. Two artists who interest me are Albert Oehlen as a painter, and Mike Kelley as a kind of American wit who has a theoretical, playful, and colorful way of looking at things, much to the expense of the ladies of New York City. Really I’ve learned to be totally indifferent to whether or not an artist whose work I’m buying “has a future.” But another side to the story is that the financing of this particular part of my work, the financing of my collecting, means that I myself have to sell more pictures, more than otherwise necessary. So there’s a price you pay for everything.

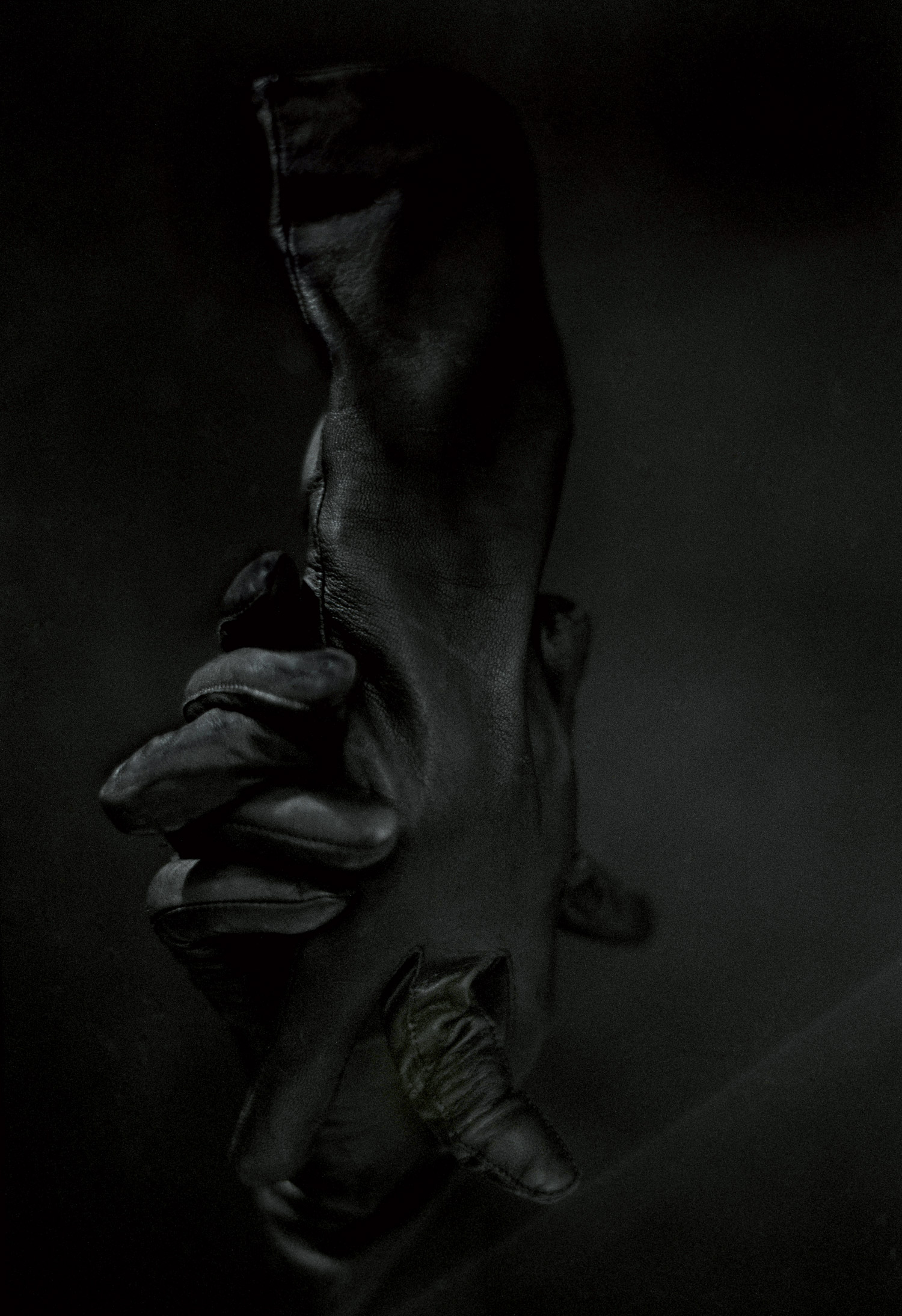

Hubert Kiecol, Meuser, and Förg also have a place in the collection. Earlier I always had a way of appropriating things by others when I thought that they were good, and of incorporating them into my own work with sculptures, objects, books and so forth. Now, building the collection is itself a part of the work I produce. Unconsciously I continue to quote from things that other people do, but today I just go blithely along with producing my own work. It also finds itself influenced by the things that my assistants contribute to “my production”; they do it on instruction, but they use their own means to contribute finished elements to “my view of things.”

JK: What are the materials you now prefer to work with?

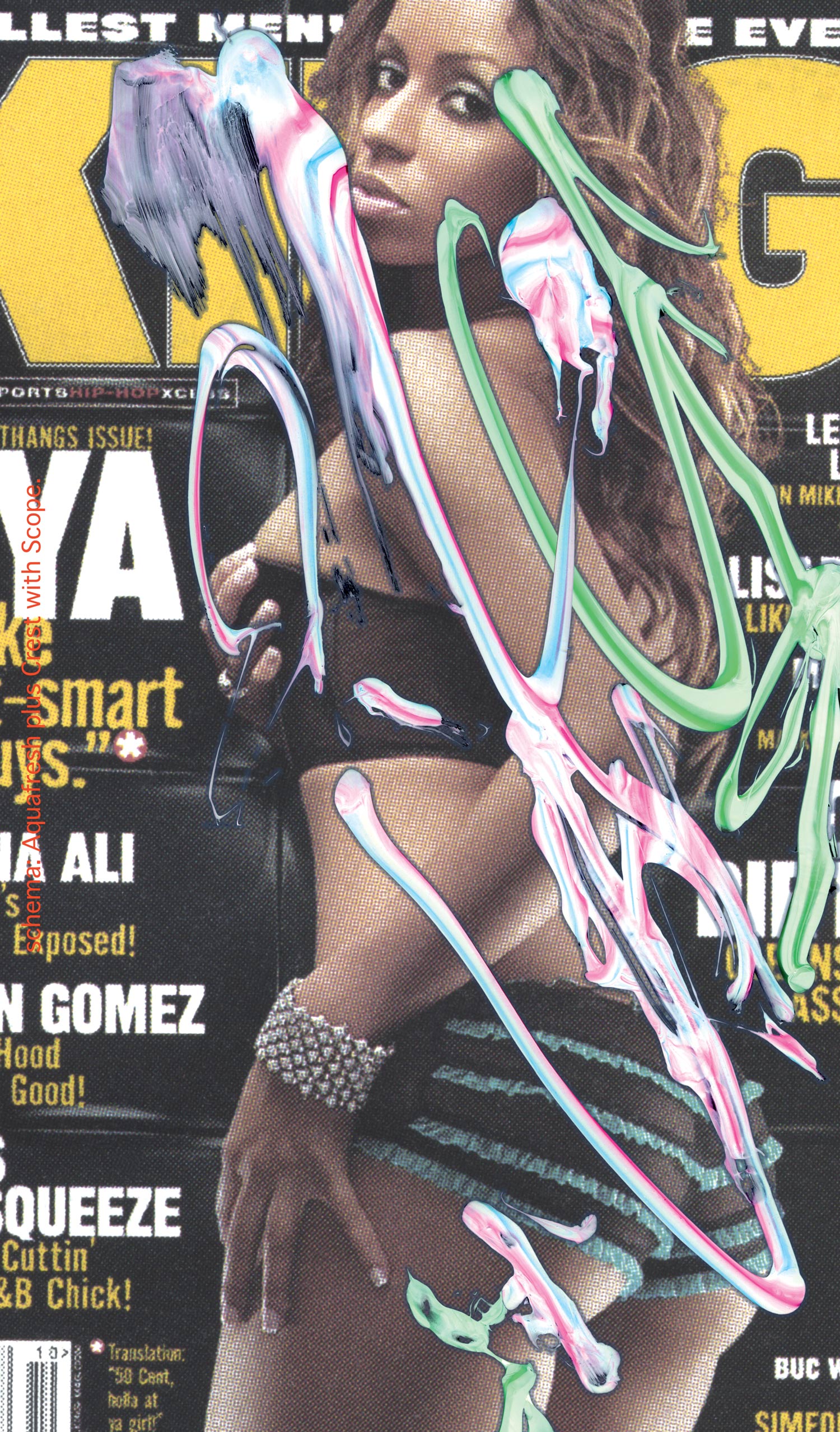

MK: Now, as always, I’m working with several at the same time, but in new combinations. In Frankfurt I’m showing bronzes, which are further developments of the lamp sculptures, but without any lamps, and it’s accompanied by a catalog that gives the first impression of a thick, expensive wine list. The reminiscence of the lamps then leads back to the question of classical sculpture. That’s the idea. The show is a comment on that sort of line of development. I’m no Giacometti; or if I am, then please for no more than three months. Then there’s more photography. Then the paintings, which by now are far too good. They’re the paintings that were executed according to my instructions by my assistant Merlin. These sorts of paintings, or commentaries, are simply too good, done far too well, which turns them into kitsch. So I decided to turn them further into a kind of double kitsch. I had them printed as very flat and colorful photographs, very glossy, and that’s how I showed them. Whereas the oil paintings themselves were cut to pieces and thrown into a trash can. As sculptures. What’s standing before you are two containers for trash with the cut up paintings inside them, and you see them through a sheet of Plexiglas. Jörg Immendorf’s old idea of “Give up painting!” is something we can always return to, expressing it once again, since it’s an order that was never followed. But today you have to understand it differently, since it no longer comes across as a way of raising some fundamental question; now it’s another luxury, rather than a part of the expression of a science. Painting can no longer be reduced to various types, like different kinds of French berets. Art treated as a science has the very same kind of listless beauty as a pointless joke; but with numberless subtleties, it has to be very well told, and very nicely reported. That’s something that an artist like Krebber is best at demonstrating. The sound makes the music. That’s what it all boils down to. That’s why Krebber will be the new hero of the 1990s. Whether he wants to be or not. The switches are already shunted onto that kind of track, and Krebber already has the look of a Number One.

With me, I’ve reached the point, in any case, of finding myself by now incapable of living a normal life. If that’s what I wanted I’d have to give up making art. Everything you present to the world is something you have to stand by. And I never let go of a work until everything private has been expunged from it. And there are people like Krebber who do that wonderfully. Everything they give is simply art. Utterly. He already has a history of his own, art just comes right out of him, without his doing anything, without sending objects into the world. All in all, he’s made no more than about twenty objects. He has trained himself so thoroughly, and for such a long time, as to have reached exactly that degree of expressive power and precision. From one day to the next, he can place a couple of things or ideas, and they sit there perfectly. He’s not interested in publishing headlines, but he establishes basic principles.

JK: What about the huge and fashionable shows — which can also achieve a lot of public impact — like the “Metropolis” show that is scheduled for Berlin in 1991?

MK: They have to exist. They’re quite important. It’s clear that Christopher Joachimides can count now on a lifetime of being asked to do exhibitions after the great success of the “Zeitgeist” show. And “Metropolis” has been conceived as a kind of counterpoint to Documenta. So it’s planned as a true and proper show of art today! It’s something to take the kids to see, like going to the zoo. Just that I’d never tell my child that this is what art’s all about.

Today’s zoo, with different sorts of animals. That’s the way I’d explain it to my daughter. This brings something to mind. My parents had five children and they’d always drag us off to museums, and mainly to the Folkwang Museum in Essen. And then my father would declare a contest, where the five of us had to go off on a search for the very best picture in the whole place. The winner was given a mark. Of course, we always went to hunt for the picture we thought our father would like the most, and not for the picture that seemed personally most important to any of us. We always started on the basis of the pictures that were hanging at home in the living room, and that led quickly to Franz Marc’s horses. So everybody came away with his mark. That wasn’t really much stimulus for free thinking. All our father really wanted was self-confirmation. And he was even willing to pay for it.

And still today that’s typical of the general understanding of art. Go to see a museum with a free mind? Sheer madness.

This brings something else to mind. None of this is of any real importance if compared to the greatest offence that has ever been dealt to art — an offence, moreover, for which the new and unified Germany has made itse0lf responsible. I’m talking about The Wall and tearing it down. That should never have happened. They ought to have left it where it was. As a monument. Inclusive of all of its terrible graffiti. Whether what I think is right or wrong makes no difference. What’s important is to manage to stick to it for a few more years.