“Perhaps there is no ‘natural way’ for an adult to walk.”

Marcel Mauss, “Les techniques du corps,” Journal de psychologie, 1935.

Berlin Alexanderplatz

On the roof of a large office building, one of the many remaining DDR-type slab-constructions, a huge electronic screen is installed to provide advertising space for a major German supermarket. But during the 1st Berlin Biennale in 1998, instead of the usual promotional short film, glamorous yet laconic commercial shots by a young Austrian artist, Markus Schinwald, flickered down on the historic square below.

The artist, then living in Berlin, displayed shoes designed by himself using a consciously ‘lifestyle’ aesthetic. For example, Mono Heels from 1998: chic women’s shoes with no soles, only a laced-on heel. Schinwald’s commercial spot makes it clear that, as one might expect, altering shoes like this make walking significantly more difficult, but the young woman on the screen holds herself bravely upright. At other times a belle with the 1998 Cabrio shoes on her feet can be seen jumping up and down. These shoes almost entirely expose the foot to the air, making them open-tops or cabriolets. The commercial spots presented at Alexanderplatz were flanked by adverts placed in art and lifestyle magazines showing stills from these ‘shoe films.’ Finally, the almost non-functional but inspiring shoes could be seen in Berlin’s Kunst-Werke, set on small pedestals like sculptures.

All the issues that are still important to Markus Schinwald today are included in this early project. Between the poles of fashion and art, performance and film, the artist investigates a charged complex that incorporates the human body, clothes of varying degrees of conventionality, linguistic code and social space. Another early example of his work, the Jubelhemd (or “celebration shirt”) from 1996 is also worth mentioning. Schinwald tailored a white men’s shirt whose sleeves left the wearer in a predicament: it could only be worn with continually raised arms, making the otherwise elegant shirt into both a straitjacket and a “celebration shirt.” This work is an apt metaphor for the mixture of euphoric new-era optimism, chic hedonism and relentless pressure to succeed financially that came with the ’90s, giving its non-functionality an instant semantic quality.

Back to the present

I visited Markus Schinwald in his studio, a former shop in Vienna’s third district [Landstraße]. Chaos reigned as usual: a noose was hung from the ceiling, engravings by the artist were displayed on the walls, various naked mannequins stood here and there, empty coffee cups waited to be cleared away and an assistant sawed wooden planks to length.

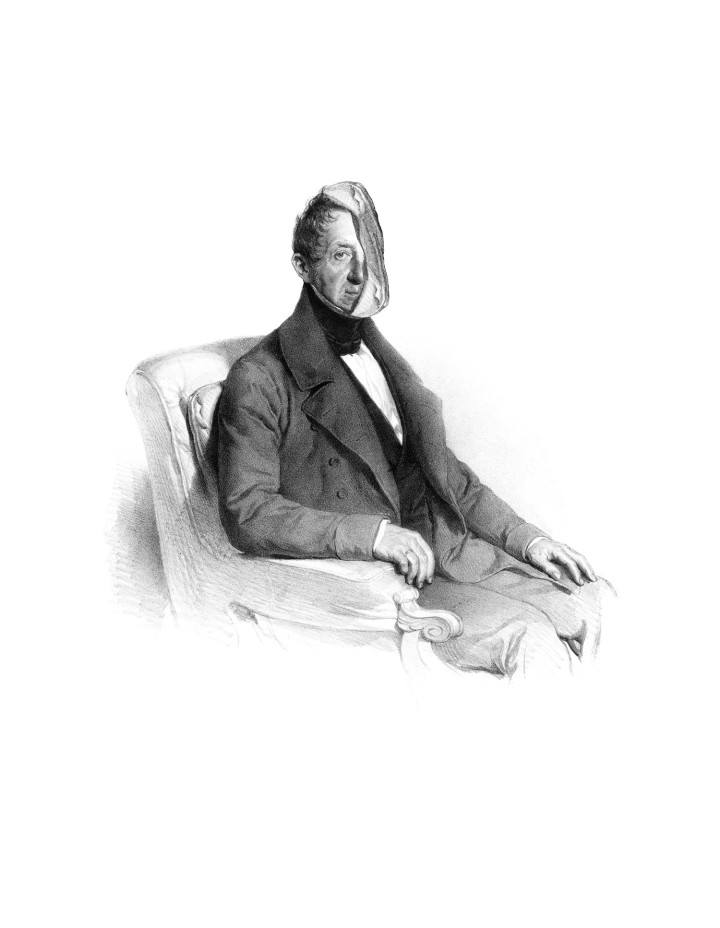

the studio had grown since my last visit (six months ago), with the addition of a roomy office space. Straight away, Schinwald talked to me about his solo show at Kunsthaus Bregenz [running through April 2009], showing me a model of the exhibition plan on a long table in front of us. The show covers three stories of the Peter Zumthor building, each of which is equipped with a stage of equal size, divided into two parts. On each of these stages, a performance-type play takes place, each on a separate day of the exhibition. These plays are filmed and shown alongside the props and the three different stage sets for the course of the exhibition. Production, reproduction and presentation go hand in hand, making the exhibition a hybrid of theater, film and art exhibition. Part of what makes it an art exhibition is that works by the artist that provide a commentary on the events of the drama are integrated into the sets. Schinwald, dressed as he generally is in an elegant, dark lightweight suit, pointed out one of the engravings hanging on the wall and told me that, among others, this work would be on display in the Bregenz show. The work in question is a pigment print taken from a 19th-century engraving, showing an apparently well-off man in a dark suit. To be more exact, the picture is of Johann — the title of the 2005 work.

Schinwald scanned the man’s portrait into the computer and surreptitiously deformed it by multiplying elements of the picture and then reshaped those elements into a jarring, disturbing vision. In this case the artist has rearranged the man’s spectacles to form a strange nose ring. Not only does the portrait lose all its conventionality and even naturalness at a stroke, this polymorphous and perverse displacement also reveals the historical dimension of fashion and the conventional dress code.

Most importantly, however, the immanent deconstruction of male fashion emphasizes that it is above all a closed system. After all, even deviation from fashion is significantly defined by its difference from what went before, and therefore remains trapped in the same frame of reference ex negativo.

Sculpture as body

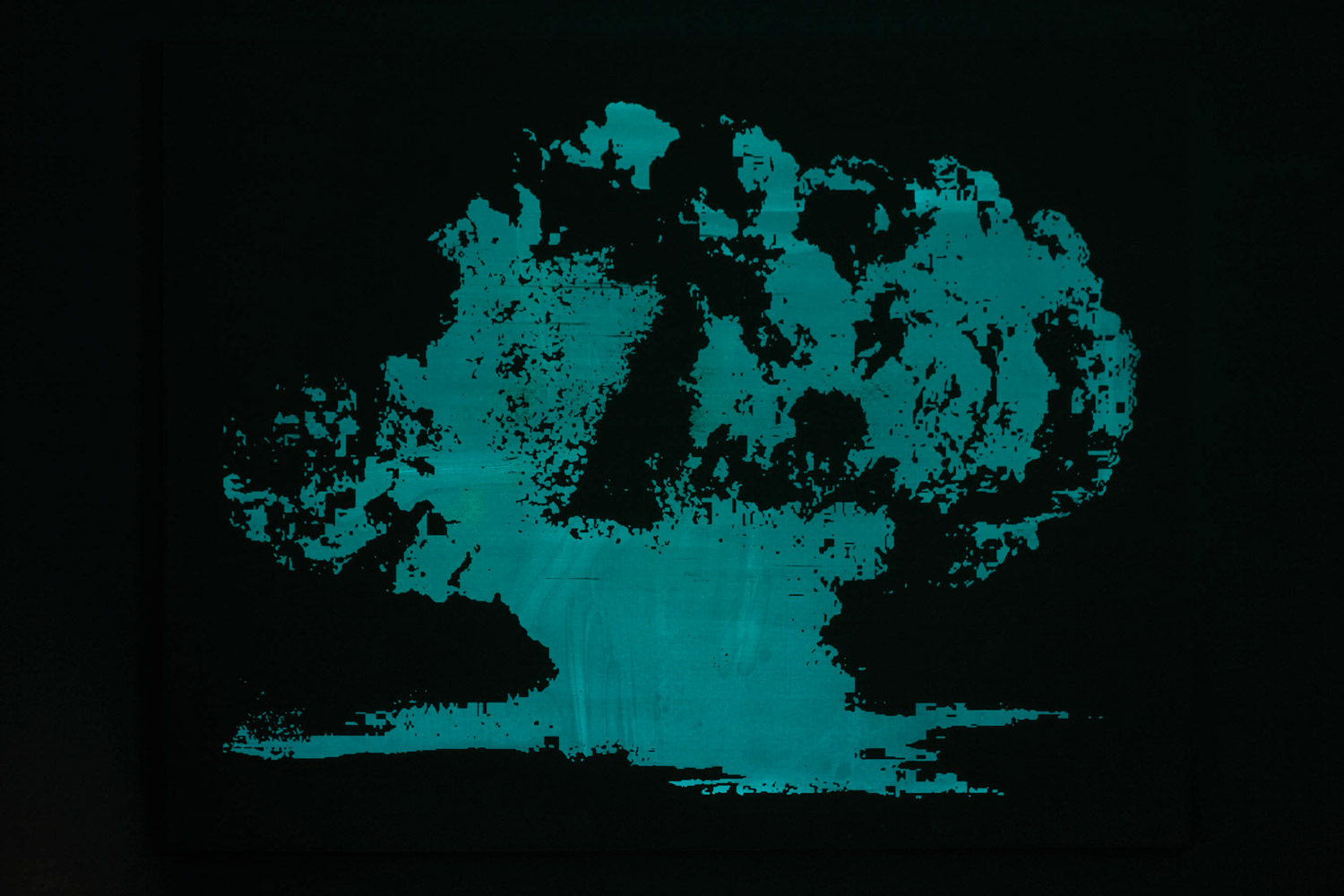

Various sculptures by Markus Schinwald also play a significant role in the Bregenz setting. For instance, Untitled (2007) is created from four wooden chair legs and occupies the space like a cross between dismembered limbs and an oversized insect. The chair legs, while not having any direct relationship to the human body, recall its movements and mime its aspects. Alongside these abstract sculptures (to a greater or lesser degree), horizontal and vertical geometric sculptural strut grids will be built into the three-stage spaces, as they were for Schinwald’s exhibition in the Zurich Migros Museum at the beginning of 2008.

They close off lines of sight and hinder straightforward sequences of movement. As with his sculptures, this enables the artist to examine the human body and its motion through the implications of how mobility is inextricably linked with three-dimensional space. This is the reason why Schinwald continually transfers his fixed pictorial and sculptural inventions into performance, theater and film, which run their course over time. This allows the Viennese artist to bring the fourth dimension of time, which for any living body is of course essential, into aesthetic play.

When asked about his three performances in Bregenz, the artist said, “I’m thinking about issues like ‘biography as a blank sheet’ and ‘masochistic triumph.’ The scenes staged also have parallels with the US TV series Seinfeld in some respects. They have a similar atmosphere to my film Dictio Pii (2001).” In that film, seven actors play out seven non-connected episodes in a mysterious empty hotel. For instance, an aging lift boy continually brushes the dust off his uniform, or a blonde woman, also no longer young, with a strange, non-functional prosthesis around her neck, smokes one cigarette after another. In the last section, a tied-up man stands motionless in front of a woman with a severe gaze. All the while, text fragments can be heard, such as “We are the perfume of corridors… traitors of privacy,” taken from, among others, the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, the fashion mogul Calvin Klein and the author J.G. Ballard. In collaboration with the French fashion designer Rene Lezard, Schinwald has conceived a breathtaking tour de force encompassing the depths of desire, fetishism and alienation.