In the recent history of Mexico, 1994 was a seminal year. On January 1 the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was ratified, and the same year the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZNL) declared its nonviolent and defensive war against the Mexican state and the military, paramilitary and corporate incursions into Chiapas. During this period of political instability the Mexican art scene started a process of change and adaptation. Over the past two decades since these initial experiments began, art in Mexico has addressed issues like poverty, labor conditions, violence, globalization and war. Miguel Ventura’s Civic Songs (2008) presented at MUAC or Teresa Margolles’s What else could we talk about? (2009) at the Venice Biennale are just two examples. The dynamism of alternative spaces in the ’90s and their institutionalization and consequential inclusion in the major art system have internationalized the Mexican art scene, going beyond the solitary leadership of artist Gabriel Orozco.1

According to Cuauhtémoc Medina, the foundation of this new structure has had three pillars: the role of the independent curator; the growth of alternative spaces and artist initiatives 2; and “the desire for independence,” a mission that has been pursued through the “openness generated by the interaction of local artists with global artistic networks.” 3

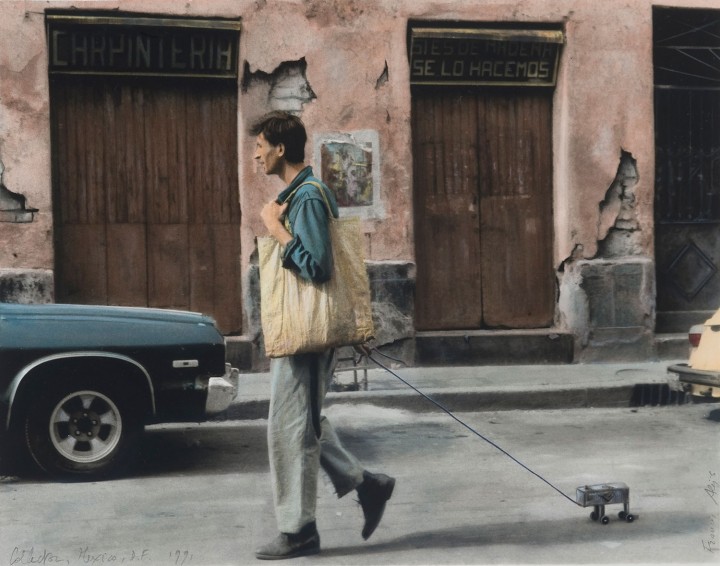

This global network was reinforced by a group of foreign artists — such as Francis Alÿs from Belgium, Melanie Smith from the UK, Thomas Glassford from the US and Santiago Sierra from Spain — who moved to Mexico City.4 Alÿs’s ambulatory and poetic actions transformed Mexico City into “a fable within a fable.” In The Collector (1991), the artist documented his action of pulling a magnetic object with the shape of a wheeled four-footed animal through the street, collecting all kinds of abandoned metal objects. The space in which things happened — the context — became fundamental, whether it was public or private, outdoor or indoor. In 1997, Santiago Sierra was invited to create a project for the re-opening of a new section of Galería Art Deposit in Mexico City. His response, Gallery Burned with Gasoline (1997), was a site-specific installation where, with the help of torches and blowpipes, he literally burned the entire space floor to ceiling, a direct attack to the institution and to the notion of propriety and law, which was then celebrated in his infamous project for the Spanish Pavilion at the 2003 Venice Biennale, where only Spanish citizens were allowed to access the pavilion and see what was shown.

Furthermore, the professionalization of the art system in Mexico became more evident in the late ’90s with the first ExpoArte and the Foro Internacional de Teoría del Arte Contemporáneo in Guadalajara in 1992, and especially when Patricia Martín started to work with Eugenio López on the establishment of the Jumex Collection — the largest collection of contemporary art in Mexico. These developments were accompanied by the birth of Kurimanzutto,5 the Patronato de Arte Contemporáneo14, the International Symposium of Contemporary Art Theory (SITAC) and the Oficina Para Proyectos de Arte (OPA) in Guadalajara.6

After many years of indolence, the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) decided to develop a contemporary art collection, and in 2006 the Museo Universitario de Ciencias y Arte (MUCA) hosted the historical exhibition “The Age of Discrepancies: Art and Visual Culture in Mexico 1968-1997” curated by Olivier Debroise and Medina. The interest in contemporary art brought structural transformations 7 within the museum landscape, which is mostly managed by the state: in 2008 the UNAM became a major player with the creation of the Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC). This in turn forced the government to increase its participation, which caused the extension and remodeling of the Tamayo Museum that opened in 2012.

From the private sector, beside Kurimanzutto, galleries like Labor, Gaga Arte Contemporáneo and Proyectos Monclova — which represents artists like Mario García Torres and Eduardo Sarabia, who have a strong presence in Europe and the US — have embraced the so-called “international conceptualism” and presented a new generation of Mexican artists who have gained attention for their critical and radical irreverence. Within this context we see artists like Stefan Brüggemann — whose sarcastic works and texts, realized in vinyl or neon and recycling material from fashion magazines, art catalogues and philosophy books — as one of the most interesting examples of Mexican contemporary art.

In 2009 the New Museum presented “Younger than Jesus,” the inauguration of its new triennial. Adriana Lara, part of the collective Perros Negros together with Agustina Ferreira and the founder of Gaga Arte Contemporáneo Fernando Mesta, presented Banana Peel (2008). Invoking the most basic slapstick, this work — which required constant security — symbolizes a specific attitude of this new generation of Mexican artists, which stands in clear contraposition to the multiculturalism of Alÿs and Orozco and has nothing in common with the strong political engagement of Margolles or Sierra.

Thanks to these different attitudes, the contemporary art scene in Mexico is solidifying more and more. Even galleries like Jan Mot and Peter Kilchmann — who represents Alÿs, Smith, Margolles and the collective Tercerunquinto — have made incursions into the adventurous Mexican landscape.8