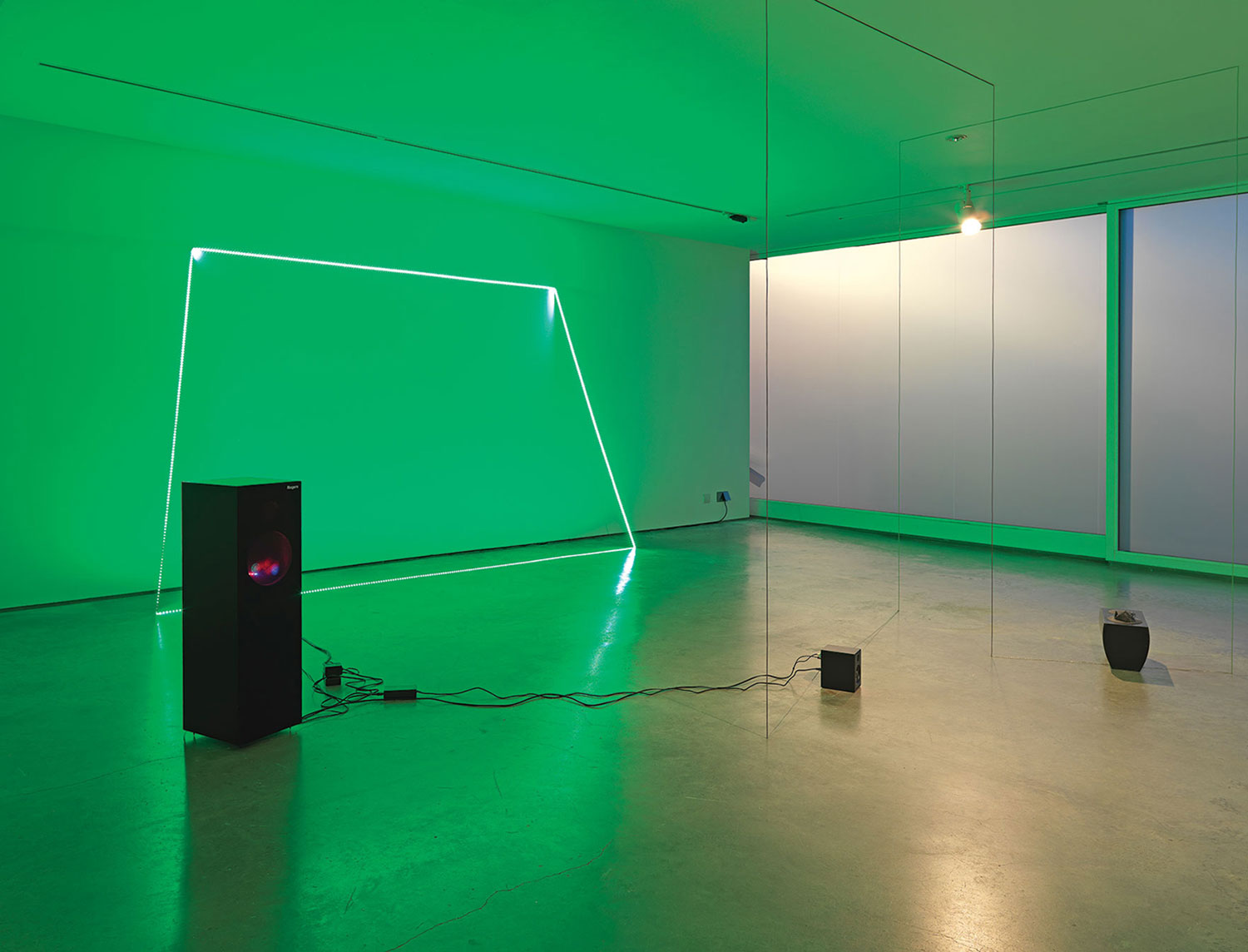

Sabine Folie: On superficial first glance one could call your work minimalist — what Clement Greenberg described as the look of ‘non-art,’ an art with a minimum of ‘interesting’ events. But on closer inspection one could, if one lived in the ’60s, align with the critique of Michael Fried, according to whom the emphasis on ‘objecthood’ was a “plea for a new genre of theater” and with it came the “negation of art” in general. Where does your penchant for ‘objecthood’ come from? Does it actually have its roots in your study of stage design at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, which ultimately led to performative ‘enactments’ in specific spaces? Both the performative and the theatrical play a major role in your work. Does one follow the other, or rather, how does performance and spatial collocation work together in your practice?

Heimo Zobernig: The avant-garde credo when I arrived in Vienna in 1977, as I found out, was “doing nothing.” On one hand it caused frustration with unproductiveness and was thus a strict school of discipline, and on the other hand it spoke to my idea of zero-growth and the blissful or serendipitous promise of laziness at that time.

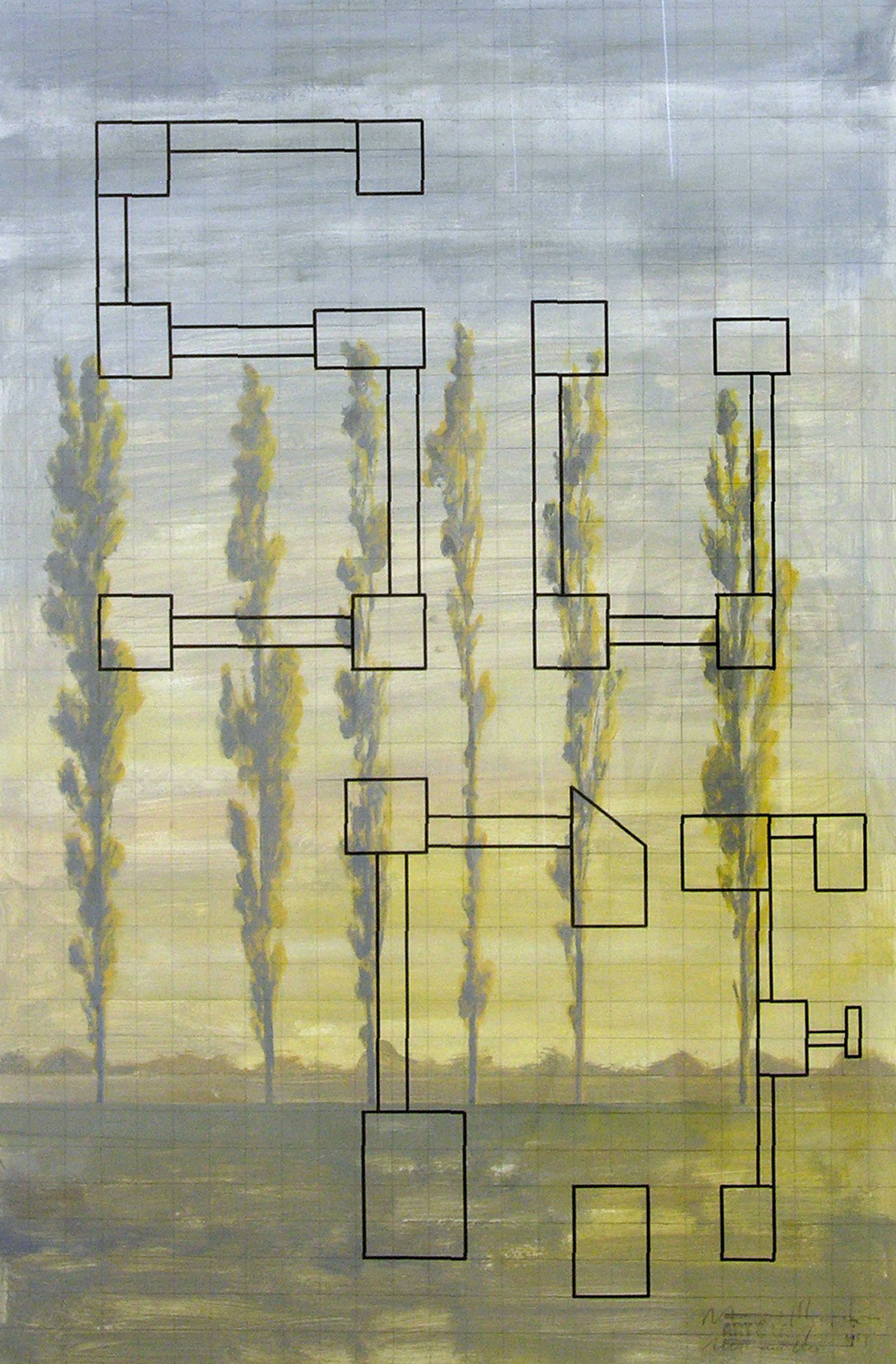

During my time at the Academy my consciousness was best cultivated in the department for stage design. Other classes were still adhering to antiquated models. Performance was the current topic at that time. The theater wasn’t particularly interesting to me, but the discourses happening there were in theory and practice well developed. After performative beginnings I then began to concern myself somewhat with props. In one variation of Marxist capital logic — “conditions determine the behavior of people” — as in — “things influence the behavior of people” — I wanted to make things that were, for example, spatially limiting or defining but also atmospheric, though not just in terms of the stage, rather in relation to architecture and sculpture.

SF: Usually you are the protagonist in your performances for video, but occasionally there are others like Hans Weigand, Richard Hoeck, Mathias Poledna, Peter Kogler or Franz West. What roles do friendship (mainly with men) and collaboration play in your work?

HZ: This isn’t exactly right. I’ve also worked with Ruth Labak, Dorit Margreiter, Lone Haugaard Madsen, Jakob Lena Knebl and others. I was once invited to an exhibition with Hans Weigand and Martin Kippenberger, and I wanted my video contribution there to strongly exaggerate the male-dominated ’80s. With the death of Martin I abandoned that work and, using just pieces of it, the video für Martin Kippenberger (1997) emerged as a kind of requiem — a farewell to that moment. Friendship is a good reason for collaboration, but not a requirement. When working with others I like the division of labor that occurs, and friendships that can result. It was never the idea that a more interesting kind of authorship would arise from working collectively. The respective interests in this cooperation are typically clear to recognize. Individuality remains but it is not the main theme.

SF: Your videos are consecutively numbered, just as your exhibitions between 1990 and 1992 were introduced with letters. Is there a special affinity for the essentiality of the simple and humble connoted sign? Where does it come from? What role does this kind of principle of double effect play in opposition, and in relation to, playfulness, or as you call it, slyness.

HZ: Through the reduction of systematic categories and obvious, simple concepts, the difficulty of insisting on the unambiguous becomes clear at best; essentiality is just an ideal. I don’t exclude the sly, playful or intuitive. I always try, as best as possible, to clearly give it a name. Contradictions, paradoxes and impurity are all material.

SF: Once again back to the nature of your work, specifically the sculptures: though at first glance your work is formalistic, it is, in applying ‘imperfection’ and Non-finito in form, execution, paint application and materiality, charged with the appearance of conscious precariousness, casualness and nonchalance. On the other hand it gives an impression of dryness, essentiality, of modesty and actually also a sense of brittleness and the poetic — emotional even. The works are cool but do not leave you cold. What are you trying to achieve?

HZ: A critique of the idea of “primary structures.” Expression and communication are unavoidable. The most minimal clues are wonderful to read within their own environments. It’s not the pathetic permanence of sculpture that interests me but rather the exemplary nature of it. That’s why a lot of my early work wasn’t really very big. The scaling was about viewing. Through diverse photographic details I wanted to indicate the tectonic. They’re meant to function like close-ups of faces or that which is suppressed or denied in film. Already with minimal texture there’s a lot to interpret, like when vacuous objects stare into the void. The desire to interpret or examine is absolutely compulsive. That’s what you can attribute the success of all these CSI TV series to. In them highly complicated criminal cases are resolved through hardly tangible signs and clues of almost nothing, and the starting points are just a couple of abstract forms.

SF: I see strong connections in the formalistic minimalism of your work to the pragmatic and utopian ideals of modernism, the Bauhaus or Russian constructivism for example. What’s your position on modernist design, materiality and color theory?

HZ: For me the modernist utopian project still isn’t finished, there is still plenty to do — postmodernism just interrupted the episode. Minimalist formalism is of course just decoration. Design that reflects our conventions and disappoints our habits is of great interest to me. I’ve been successful with the employment of color theory but there are however many cultural, historical errors and traps in perception to still discover. Color theory is a branch of science that has no conclusion. Art is in this sense the perfect science because it’s impossible to objectify color.

SF: You received the Kiesler Prize in October. Are you happy about the prize? Does Friedrich Kiesler — pioneer of surrealist stage design, exhibition design and architecture of the 1920s — play a role in your work?

HZ: I’m very happy about the Prize. It’s one of the most renowned in art and architecture. It’s wonderful to join the list of prizewinners. Kiesler’s rediscovery and recognition has been a part of my own biography since the ’80s. I’ve never named a leading influence, but Kiesler holds a special position because he, along with very few others, devoted himself to the theme of exhibition as exhibition. When I was developing the design for the corporate logo of the Vienna Secession I wanted to replace the C with a Z. Friedrich Kiesler did this with his plaque from 1928 at the International Exhibition of New Theatre Techniques he organized in Vienna in 1924. My suggestion however was unfortunately not accepted. It was realized only one time for Herbert Brandl’s catalogue in 1999. With the pointed Z, Kiesler avoided the curvy Art Nouveau C. This was a reference to, and reference for, Friedrich Kiesler.

SF: With consideration to various genres like sculpture, painting, typography, design and performance, you approach motifs like color, grids or abstract structures. How important is the proliferation and reworking of certain themes in various mediums to you?

HZ: Every medium is specific and has its own historical development. All content contains another form or deformation. The first time I showed videos in an exhibition context my intention was to emphasize the difference between them and the images on canvas. It wasn’t the idea to present a concept through various mediums, the idea was rather to show the videos as contradictory commentaries. Nevertheless there were intersections that show how video images lead me to painting, sculpture or space and vice versa, but this was not intentionally.

SF: Is there such a thing as beauty for you? What role does it play, or can it play, in sculptures that fundamentally question the conception of art and all the –isms, and which are allocated with opposing attributes: not only with the modernist rationale, the tabula rasa, but also with the magical, sinister and fragmentary.

HZ: For a long time I had the feeling that beauty isn’t important to me, and it just unfolds. But the search for the truth in the truth, for the fundamental working mechanisms of forms, of unconscious patterns of perception, is an aesthetic problem. Beauty is often that which is not describable. It is always there but as an artist you always arrive at it a bit too late. Perhaps it’s in this, the small interval of lost time, that the magical, sinister and fragmentary exist in my “seemingly sober, non-transcendental view of the world…”

SF: The aesthetic penetrates all forms of your artistic production right up to your special relationship to fashion. In the ’90s you had tailor-made suits made from one single pattern. Now you have given these suits to designers Jakob Lena Knebl and Markus Hausleitner to create a new collection from them. The collection was recently presented at Galerie Christian Nagel last year by prominent models (Kaspar König, Kitty Kraus, Helmut Draxler, etc). The result was reminiscent of deconstructivist designs by Rei Kawakubo, Thierry Mugler or Yohji Yamamoto from the ’90s. Is there a resumé present or a certain amount of nostalgia, like in some of your other works?

HZ: Martin Margiela should also be mentioned here; there are undeniable references to his work. No, to present a resumé of that time was not my intention and nostalgia doesn’t plague me at all. The exhibition title “Alte Sachen” (Old things) was dedicated to 20 years of Galerie Nagel. There I had the opportunity to show works that had previously been seen in other exhibitions in a new way, which can perhaps be seen as curating my own work. It was a way to see if those works could still be considered contemporary. The installation of the fashion show with the raised stage, spotlights and sound system fit perfectly with the sculptures. I wanted to take clothes from this time out of the closet and clear them out so as not to appropriate the camouflage style of the time. A small spectacle in the form of a fashion show seemed to be appropriate for a 20th anniversary celebration. Jakob Lena Knebl and Markus Hausleitner have the right amount of disrespectfulness to constructively destroy the material of these suits. The name of their cooperative label, house of the very island’s club division middlesex klassenkampf, but the question is: where are u, now?, says a lot about their aims, and the exhibition plaque, a photo work by Jakob Lena Knebl, offers even more clues… wearability is often contrary to appearance. All the invited performers had a visible sense of well being in the clothes, as if they were tailored to every respective type, but that was incidental.