Had Carlo Mollino (1905-1973) never existed, he would have almost certainly been imagined — the fictional embodiment, something between Moravian playboy and the architect in some Ayn Rand novel, of a delirious modernity actually lived at breakneck speed. The hyperbole would not have suspended disbelief: alongside architecture, among the real Mollino’s avocations during his lifetime were aeronautics, motoring, skiing, scenic, graphic and interior design, photography, writing, the occult, and the patenting of fifteen heteroclite inventions. He flew airplanes and raced cars of his own devising; wrote a novel, a handbook on downhill skiing, and a treatise on photography; he designed furniture and interiors as well as cutlery, women’s dresses, gloves and shoes. Mollino was a student of rhabdomancy and horoscopes, while also patenting a process for the bending of plywood.

If eclectic range doesn’t stretch credulity, then Mollino’s obsessive breadth — his prodigious ability to unite these variant interests into the production of architecture — should. The trussed glass-top and molded wood tables of the ’50s, perhaps Mollino’s signature, draw directly on the tensile curved constructions of aerobatic aircraft, for example. This eccentric unity of autobiography and late Futurist modernization means the Mollino corpus simply resists any summary attempt to abbreviate it. Mollino as paid-up Corbusian obscures an “original and ironic version of organicism,” in Manfredo Tafuri’s still-apt description, that might define his elusive place in postwar Italian architecture. An ‘occasional’ architect, slouching late in life towards a Turinese ‘baroque,’ Mollino’s furniture and interior design also evince a unique theatricality, underscored by what seems like a return of the repressed of architectural modernism: eroticism. An erotic imaginary is suffused throughout Mollino’s body of work, from the bodice-shaped plan of the Teatro Regio in Turin (1965-1973) to utilitarian objects that are supposed to allude to (an albeit highly idealized) female anatomy.

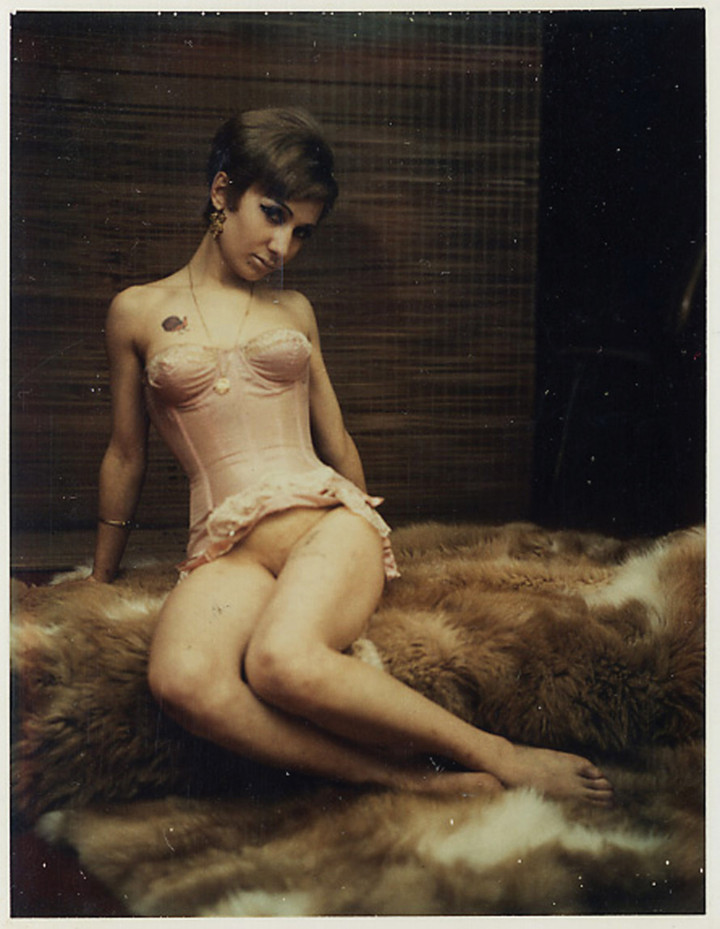

No surprise then that this exaggerated persona, hurling itself towards the postwar era with all the frenetic energy of Marinetti’s cult of speed, left behind its own perverse erotic inventory: thousands of photographs and Polaroids of female nudes, taken in interiors and on furniture of his own design, starting in the ’50s. Mollino, it turns out, even produced his own pornography.

That word usually entrains a mephitis of lust and guilt. Mollino’s photographs — among the incunabulum of architectural pornography that includes advertisements for Saarinen chairs and ’60s issues of Playboy — would be utterly insipid if mere examples of the common quiddity of individual fetish or transgression of some clichéd taboo. The eroticism in Mollino’s photography is also by now staid; in one image, a corseted figure bares the initials “C. M.” on her bare ass. Such photographic burlesque, of the Olympia Press variety, has been completely domesticated. That, in fact, only belies the particular significance of the images.

Rather than the pornographic display of sexual organs, the photographs point towards what Barthesian theory might deem a desire beyond what the image permits us to see. The mise-en-scene, the staging of seduction, in fact foregrounds Mollino’s own contribution to an architectural trope of postwar consumer society. The eroticism, a leitmotif in the Mollino interior, is enacted precisely in a new kind of domestic space, one that while denying the mores of bourgeois sexuality (specifically, the postwar bachelor’s defiance of heterosexual marriage) also proposes an architecture liberating the modern man from conventional morality (thus ‘freeing’ desire).

Most of the photographs and later Polaroids were taken in private environments Mollino called his garçonnières — roughly, “bachelor quarters” — functioning both as photographic studio and erotic milieu of backdrops, curtains, fetish objects, mirrors and assorted trompe-l’oeil mechanics used to create a Lapidus-like “architecture of persuasion.” These interiors, as Benedetto Gravagnuolo has written of those designed much earlier by Adolf Loos, are explicitly meant to “protect the private sphere from public morality.” They are Mollino’s version of a new domestic architecture proposed by Playboy centerfolds of nude women on modernist furniture and in designs for ‘bachelor pads’ published in the magazine, of which Mollino was an avid collector, in the ’50s and ’60s. Interiors also designed to facilitate or stage seduction, the garconierres allow precisely for the type of intimacy that makes Mollino’s erotic photography possible at all. Mollino in fact lived with his mother a majority of his adult life — an irony both Victorian and Warholian in its allusions. The garçonnières rethink, if rather chauvinistically, the place of sexual intimacy in postwar domesticity.

The photographs capture this new type of private pace through the technologically mediated seduction afforded by the camera, in particular, the instantaneity of a Polaroid. The ‘tense’ of the photographic event, the staged eroticism in Mollino’s photography, is thus slowed down by technology; these frozen tableaux document intervals of the flow of sexual seduction, detaching themselves from the proceedings as an object while also functioning to facilitate them. Mollino himself draws on such an example in his description of the implications of photographic technology: “Once upon a time, when you wanted at a moment to say ‘Stop, you look wonderful,’ you had to place the head of the patient destined to impersonate it in a vice, while allowing a hazy emulsion and a pedantic piercing lens to take their time; today, that moment lasts thousandths or billionths of a second…”

There is perhaps nothing as tedious, in the realm of sexual seduction, as the banality of its often-elaborate orchestration (true from Kierkegaard’s Diary of a Seducer to this year’s blockbuster movie He’s Just Not That Into You). In Mollino’s case, this was no different. The photographic sessions that produced the images involved the procurement, usually by his friends, of nightclub hostesses. Dinner parties were sometimes held as elaborate ruses. Mollino was no laureate of the ‘pick-up,’ but he certainly was an excellent dramaturge.

The first of his garçonnières was a small apartment in the hills overlooking the city of Turin known as the Villa Scalero, rented in the mid-’50s. The corresponding images, at first taken with a Leica, have as their central props a bed designed specifically for the space, as well as a black-lacquered, spine-shaped chair, the arabesque ‘female’ line of which is enforced by several photographs of models tracing its contour with their backs. Mollino incorporated three other pieces of furniture previously designed for his first bachelor’s apartment in 1946 (known as the Mollino Apartment): a cylindrical writing desk — the focus of much attention in the photographs — and a sculpted chair in natural poplar. Models were posed on or against these pieces of furniture wearing the dozens of dresses, bits of lingerie, various accessories and shoes in Mollino’s own collection. Several women were often photographed in the same garments; a diaphanous white skirt makes a frequent appearance throughout the images, worn in all manner of subtle variations.

Most of Mollino’s photographs were subject to much retouching after they were taken, worked directly with ferrocyanide and a brush, used to lighten an image or define contours. Mollino had already made deft use of photomontages early in his career, and carefully composed the photographs of his interiors published in architectural journals. This “all is permitted” approach to the darkroom is directly stated in Message from the Darkroom, his 1949 treatise on the history of photographic taste and the poetics of technique:

“A photograph can be permanently defined at the moment of the first click, which is the necessary condition for its existence, or come to life at any point in the subsequent series of aesthetic operations… all those operations that range from accelerating the appearance of the details only touched upon by the lens with the heat of your hand to rushing anxiously to raise tonalities with cottonwool, or worse still, fingers damped with red prussiate and hyposulphite, and even abolishing entire disturbing parts of the image, right down, to the native outrage of the purists, to dangerous and interfering retouching of the negative or positive, superimposition and photomontage: all is permitted.”

Around the same time Mollino was restoring a rented 19th-century piano nobile apartment in the center of Turin, he purchased his first Polaroid camera, a model 800 with manual focus and adjustable aperture. The construction of this highly symbolic and lavish interior, with references to Egyptology and mystical tradition, was to occupy him from 1960 until his death in 1973. The majority of his Polaroids, a format used almost exclusively through the ’60s, were taken in this eccentric interior and in yet another similarly arranged garçonnière created at the same time, the Villa Zaira. Here Mollino begins to minimize the modernist emphasis and focus more intently on tenebrous erotics of moodiness and ambience (think, Emmanuelle). The instantaneity of the Polaroid image in these settings only emphasizes the ‘tense’ of the staging further: one can imagine Mollino and his models assessing (enjoying?) their erotic ‘readymade’ object together, making decisions on poses and props, the instrumentalized seduction turned into a game between the devouring eye of the camera, the desire involved in seeing oneself in such an image (immediately gratified), and the intimacy made possible by the perfection of a not-so-subtle architecture of sexual persuasion. Here, modernism is always creeping: cue nude-woman-on-modernist-chair, and of course, bring out the flowing white skirt.