Confronted with Robert Kusmirowski’s work, one is immediately immersed into the past. Kusmirowski’s oeuvre explores ideas of history and its representation, as well as memory, but also demonstrates in an uncanny way the artist’s identification with an imagined collective past. Working in a variety of media, all his work is painstakingly handcrafted and constructed in such a way as to appear as if it were a genuine relic of the past, excavated from the annals of early 20th century history. Kusmirowski’s sculptures and installations consist of meticulously two- and three-dimensional objects made with paper, cardboard and wood as some of his basic materials. Such is the perfection of his craftsmanship that his works bear the patina of time in a manner that completely subverts the fact that they were made in the present. Kusmirowski’s practice consists primarily of falsifications, fakes or forgeries of situations, ordinary objects of different sizes (from stamps, vintage photos and postcards to bicycles), and reenactments and performances which refer to events that occurred or might have occurred long ago, recreating an intimate iconography of the past. Most of his works appear as though they could have been taken out of a historical museum, and indeed everything the artist produces looks as if it exists in a time capsule and feels almost awkwardly uncomfortable in the present. In that sense Kusmirowski manipulates not only objects but also time and place; he plays not only with history but with the ideas of change and transformation that go with it and how these might be inscribed retrospectively into the physical world around us. The illusionistic quality in his work is physical but also metaphorical, questioning the boundaries between reality and artifice, original and fake. It is no coincidence that Kusmirowski began his artistic career as a copyist of documents and objects from the Polish People’s Republic, his country of birth. There are no simple appropriation tactics to be found in the artist’s practice; rather than appropriating objects or images, as is customary, Kusmirowski appropriates an idea of the past, whether imagined or mediated.

He fuses real historical events and incidents with imagined ones, often inserting himself as protagonist in certain situations to create a hypothetical sense of individual or collective memory, an open-ended mental space about which each of us can hypothesize, fantasize and reflect on. The simulated patina and precise craftsmanship of his work thus creates a nostalgic atmosphere of bygone times that operates by association and evocation rather than as a straightforward narrative. Kusmirowski thereby activates cultural memory but also stirs up an ecumenical sense of nostalgia and melancholy, something many people experience as they grow older. There is a certain fatalistic aspect to his work and also a fetish that goes beyond the historical, a kind of artistic obsession/identification with the aesthetics and lifestyles of times past. In addition, his work is also a poignant comment on the fragility, futility and fleeting nature of life. The viewer must suspend disbelief at all times.

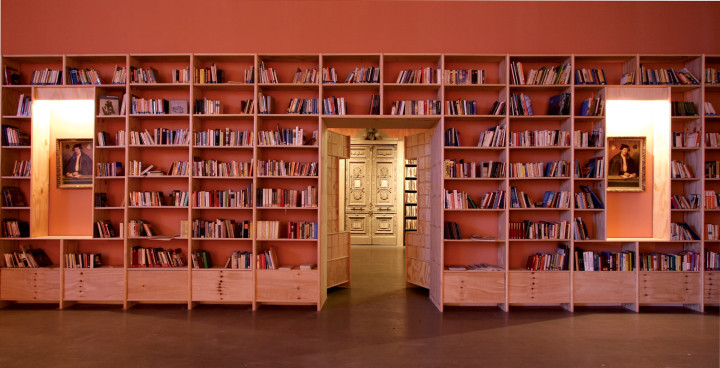

In one of his first large scale installations (D.O.M, 2004), Kusmirowski made a recreation of a Polish cemetery for the Foksal Gallery Foundation in Warsaw. At the Ujazdowski Castle, Center for Contemporary Art in Warsaw, and then later at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, he made a life-size replica of a Communist era artist’s studio which mirrored itself (Double V, 2005). In 2004, Kusmirowski completed a walk from Warsaw to Paris (Map of Auschwitz, 2004), which is documented in two photos and a map/itinerary of the countries through which he walked. The walk is a reference to Constantin Brancusi, who walked from Bucharest to Paris one hundred years earlier. At the 4th Berlin Biennale, he presented Wagon, a work initially made for Novart, Festival of Young Art, in Krakow in 2002: a full scale simulation of a ’40s transport wagon from a train. The work was haunting with its realism — including the smell of old railway carriages — bringing to mind, among other things, the hundreds of trains that made the sinister journey to concentration camps.

Kusmirowski performs magic with his materials, creating a sense of illusionism so akin to reality that one cannot believe it is a counterfeit. In this sense he is an artistic Houdini that leaves no clues as to the means by which he performs his magic deeds. The artist conjures an entirely fascinating and uniquely personal, nostalgic retro-world, which is as immersive as it is escapist. However, through digging up the ghosts of the past, Kusmirowski prompts the viewer to reflect upon the present.