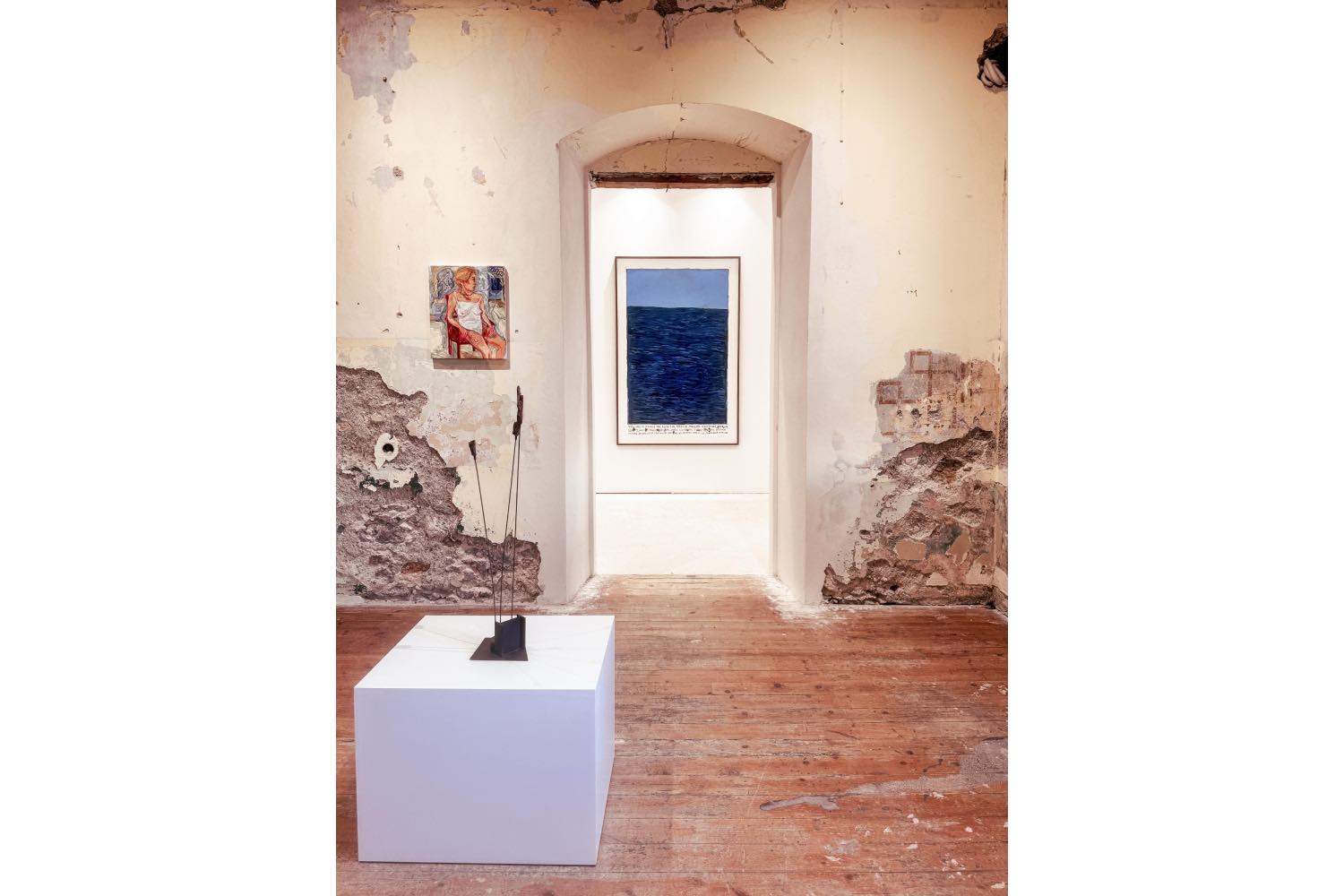

Just off the coastline of Asia Minor, the Greek island of Leros is a palimpsest of colonial history, layered with traces of its past, including four centuries under the Ottoman Empire, occupation by Mussolini’s Italy, and subsequent capture by the Nazis during World War II. The exhibition “Folding the Sea into Dresses that Dissolve Like Salt,” curated by Turkish duo Burcu Fikretoğlu and Gizem Naz Kudunoğlu, engages the island as a conduit for contemplating the continual shifting of personal and collective identities across the works of twenty-seven international artists. Perasma inhabits the evocative spaces of the neoclassical Kandioglou Mansion — one of many built by Lerian merchants returning from Egypt in the late nineteenth century with profits in their pockets — where most of the show unfolds.

Like the island, our bodies are imagined as permeable vessels, floating among slippery spheres of influence. Dutch artist Joline Kwakkenbos’s luminous, sexually charged portraits of herself adopting various personas within vivid backgrounds populated by metaphysical alter egos — such as Whispering of Artemis (2025) — hang throughout the sun-drenched rooms of the villa and in an outdoor pavilion, designed by Ömer Pekin. There are also ghostly grayscale portrayals of local Fascist buildings by Laura Footes, such as the formerly Catholic Chiesa di San Francesco, now the Orthodox Agios Nikolaos, under a bright moon. The horizontal strokes rendering the rotund buildings in Lakki Cinema, Porous Souvenirs (2025), along with the blurs of lone fleeting figures, invoke the unremitting tempo of transformation.

We are all shaped by the legacies of continual invasion and migration since the beginning of civilization, just as Leros bears the marks of its own history, obscured by the tranquil routine of daily life. The Ottoman reign ended in 1912, when Italy seized the strategic island, which has the largest deep-water port in the eastern Mediterranean, along with the eleven others of the Dodecanese archipelago. In recent years, Leros has been a key port of arrival for asylum seekers, with a major refugee processing hotspot established on the site of a former Italian barracks — previously repurposed as a royal technical school, an internment camp for leftist exiles during the junta dictatorship, and a notorious mental institution.

Among the abandoned military installations left behind is a parabolic hilltop structure formed of curved cement walls designed to identify the location of enemy aircraft. Called Muro d’Ascolto, it conjures a sculpture by Richard Serra, with goats grazing around it. Yet the device proved ineffective against the relentless German bombardment that led to the decisive Battle of Leros. More than four thousand Italian prisoners of war perished in the crowded holds of a steamship headed for Piraeus when it sank. The worst maritime disaster in the Mediterranean, the tragedy was long unknown due to Nazi censorship.

Yet our identities are shaped by those who wield the official pens. A Rationalist primary school in the Mussolini-planned town of Lakki hosts Gülsün Karamustafa’s site-specific installation Mother Tongue (2025), which names native languages forbidden by occupiers — just as Greek was banned under the Italian Fascists — in labels displayed on classroom-style bulletin boards. The title is scrawled in black ink on paper dresses, strung on clotheslines across the stark portals of the courtyard. We are separated and united by language, mere marks on a page: Ali Kazma’s Calligraphy (Resistance Series) (2013) follows the meticulous movements of a scribe’s handcrafted pen across a white page, forming elegant sweeps of ink that appear abstract to the untrained eye. National identity is both education and indoctrination – an instrument of control, often used to divide societies. Despite the ongoing acrimonious political relationship and violent history between their two nations, Greeks and Turks — who make up about half of the visitors to Leros — coexist harmoniously, using different names for the same dishes and many other common cultural elements.

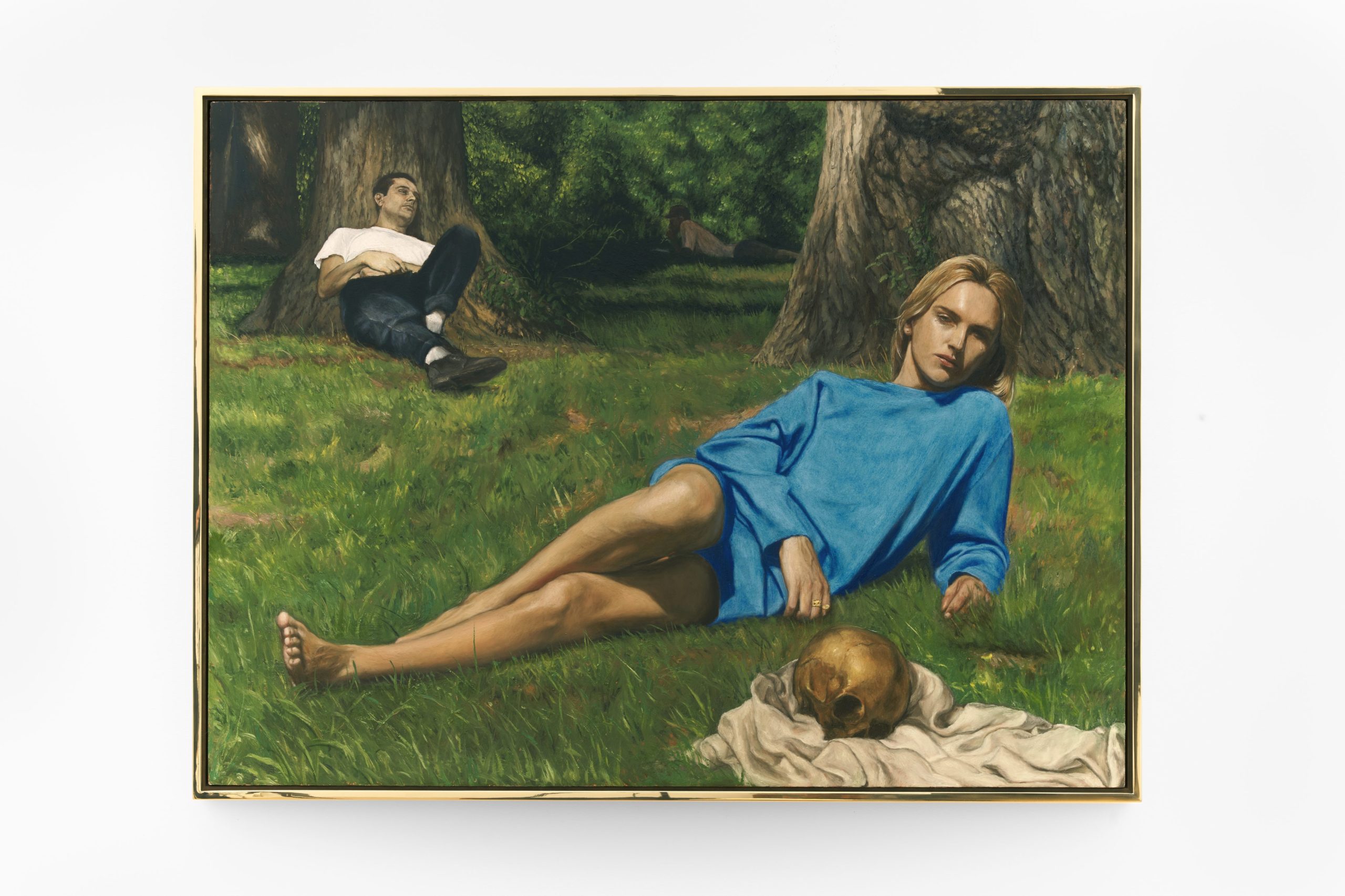

In a wayward world, we grasp for anchors. A 2023 painting by Rinus Van de Velde depicts a solitary boat sailing atop a voluminous swell of sea with the handwritten caption: “You try to disguise the form and, through improper adaptations, obtain a deputy, which is purely personal, while just below it, the true will always continue to show itself, over which you have no control and is in constant motion.” As a threshold between departure and arrival, the sea is a metaphor for the churning collective consciousness — the ever-changing fabric of reality — that we navigate alone and together. Mounted on the raw, exposed surface of a stone wall, Lola Montes Schnabel’s ceramic composition The smell of fear (2025) is a topographical likeness of an island, in bright yellow with a blood-red tip, writhing in dark, turbulent waters. Yet perception changes when the horizon becomes the center. Nearby, the film Aqua-Rêve (2009) follows the mesmerizing underwater movements of her mother in a transformative moment, after jumping into the sea to overcome a lifelong phobia.

Kostis Velonis’s paintings convey a state of fluidity in the tension between isolation and coexistence. The colorful People Were Mostly Weather (2025) summons an enigmatic, mystical fable populated by objects — a hand, a sphere, two figures — that are nearly identifiable yet ultimately unnamable. In Monument to a Shadow at My Studio at 2AM (2025), an imposing black specter looms on the verge of exiting the frame, at once menacing and endearing in its resemblance to a fuzzy beast — or the artist’s psyche? The midnight-blue background, streaked with splinters of light, echoes the peeling layers of the walls: an accidental timeline revealing hints of the building’s past lives. On a pedestal opposite, Lucio Fontana’s dynamic terra-cotta Octopus and Shell (1937) entwines the mollusk with the bulging watery form as if vanquishing or becoming one with it.

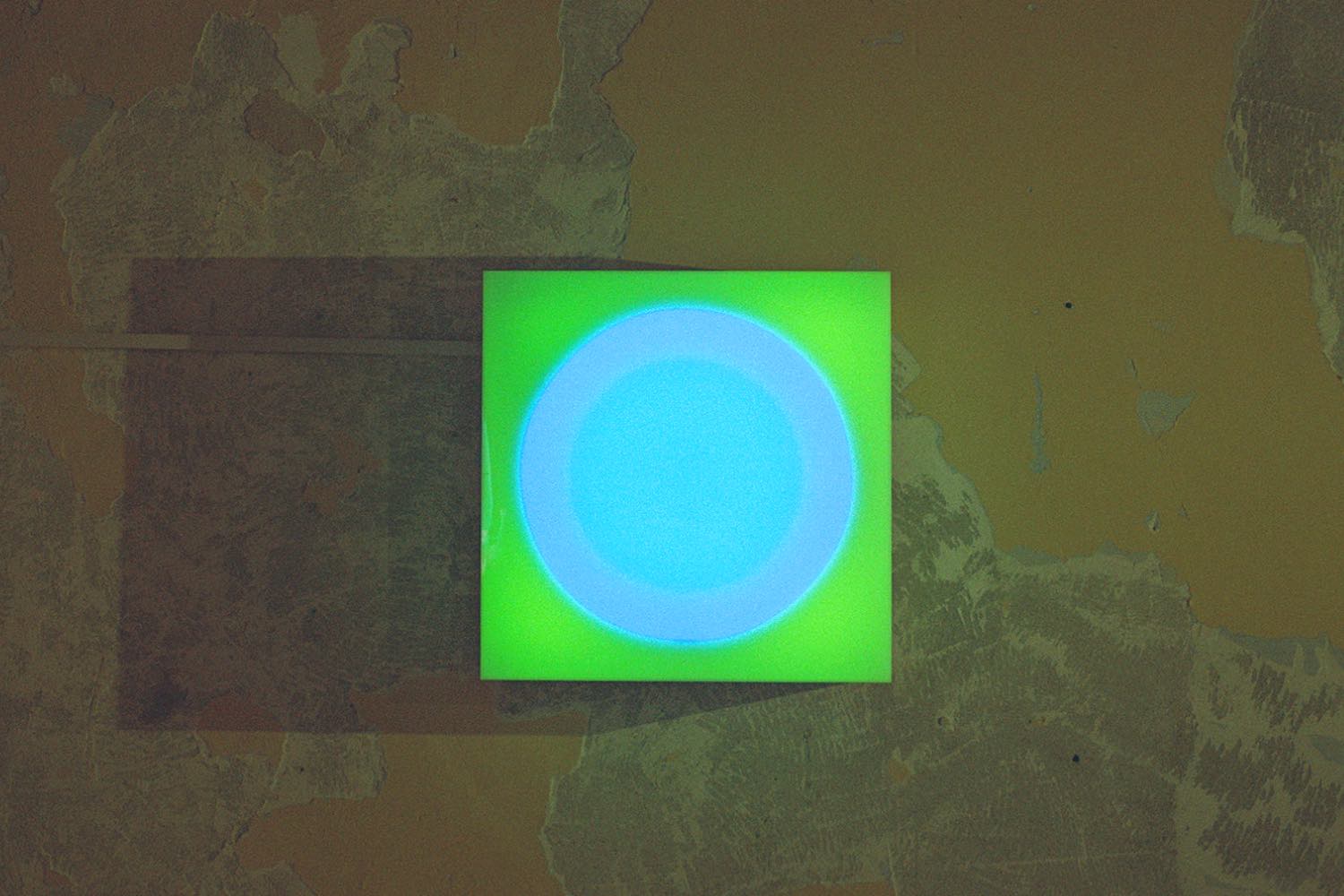

To resist may mean to merge. Korakrit Arunanondchai’s visionary film With History in a Room Filled with People with Funny Names 4 (2017) follows mysterious rituals and multifarious hybrid beings that intertwine in a cacophonous alternate reality beyond a coherent language or single culture. Boychild embodies an androgynous green humanoid whose speech is limited to light emitted from her mouth. The future is here; the future is unknown: Margherita Chiarva’s enchanted black-and-white photographic collages portray shadowy, anonymous places with an air of the exotic, all regulated by the mutable cycles of the Moon. A text on the wall reads: “You are not one self. You are many. A constellation. An inner archipelago.”