Have you wondered why the inside of your head feels so strange these days? We think you’re morphing into something else. We call this “The Extreme Self.”

What follows is a sample from our next book. It charts the transformations taking place in individuality and in crowds — emotionally, socially, and spiritually. It’s also a sequel to our previous title, The Age of Earthquakes: A Guide to the Extreme Present. Like that book, The Extreme Self is designed by Daly & Lyon, and the imagery predominantly comes from seventy of the world’s foremost artists, designers, filmmakers, musicians, and more. We asked them to send us portraits or self-portraits. Why? Because the “face” has become the basic unit in what Shoshana Zuboff calls the “age of surveillance capitalism.”

The Extreme Self was previewed in a large-scale exhibition we curated at MOCA Toronto, titled “Age of You,” which travels to Jameel Arts Centre, Dubai, in 2021.

Here’s a discussion charting the evolution from “the extreme present” to “the extreme self” in our extremely uncertain times.

Shumon Basar: Flashback to 2017. We were in Hans Ulrich’s office at the Serpentine Galleries in London. There was a palpable whiff of something unsettling in the air. Earlier that year, Trump had been inaugurated as president of the United States. White supremacists, neo-Nazis, right-wing militia, and the Ku Klux Klan had recently marched in Charlottesville, Virginia. Timothy Garton Ash described this geopolitical moment —when nativist politics was taking over, and it seemed like democracy was voting to annul itself — as “like 1989 in reverse.”

Douglas Coupland: It was the point when we knew we’d crossed a border into utterly new cultural territory.

SB: Totally. It was also clear the alt-right could meme way better than the political left. This was one reason they were winning the disinformation wars.

Hans Ulrich Obrist: Then, somehow, the three of us began to discuss our shared love for Eric Hobsbawm’s book The Age of Extremes: The Short Twentieth Century, 1914–1991. Hobsbawm had been a young boy in Germany when Hitler came to power in 1933. This set him on a path of lifelong Marxism, based in London. Eventually, he also became a mentor of mine, and a close friend of the Serpentine Gallery’s.

SB: He really was a titan. And, if I recall, Hans Ulrich — who’s always manically doodling like Robert Walser used to — wrote down some words. “The Extreme Self.” It felt like a eureka moment. We knew this was the direction to explore in a new book and exhibition. Doug, our first book together, The Age of Earthquakes (2015), introduced the “Extreme Present.” How does the extreme self follow on from The Extreme Present?

DC: Well, The Age of Earthquakes articulated how we inhabit a world that has profoundly morphed away from the twentieth century. That book was sort of a birth cry. Much of it was written in 2012–13. My worry has been that the pace of culture might outstrip the book’s perceptions, but its ideas are aging crisply. I think that for older people, The Age of Earthquakes is a guidebook. For younger people it’s like those super obvious rules they post on the walls beside swimming pools.

Fast-forward to now: The Extreme Self explores the mutation of personhood inside the “extreme present.” It’s about our interior worlds more than the exterior world. It asks, “What does being ‘you’ mean right now versus, say, ‘you’ of thirty years ago. And what is a ‘group’ compared to 1990?”

SB: Then COVID-19 came along and pushed us even faster and further into the twenty-first century.

DC: It really did. I do find it remarkable how, with 9/11, the twentieth and twenty-first centuries broke away so cleanly from each other. Even to watch an episode of Friends right now feels like temporal ecotourism, which is probably why it’s so massively successful in streaming format.

HUO: We then decided that we’d take the bone structure of Hobsbawm’s The Age of Extremes and update it for our current world.

SB: Something stood out for us. One of the central theses in his book was that the twentieth century was defined by a struggle of binary ideologies. You had half of the world invested in fetishizing the almost divine rights of individualism, which culminates in Ronald Reagan/Margaret Thatcher 1980s neoliberalism. The other half of the world was told that the individual had to sublimate their desires for the good of the common collective, aka communism.

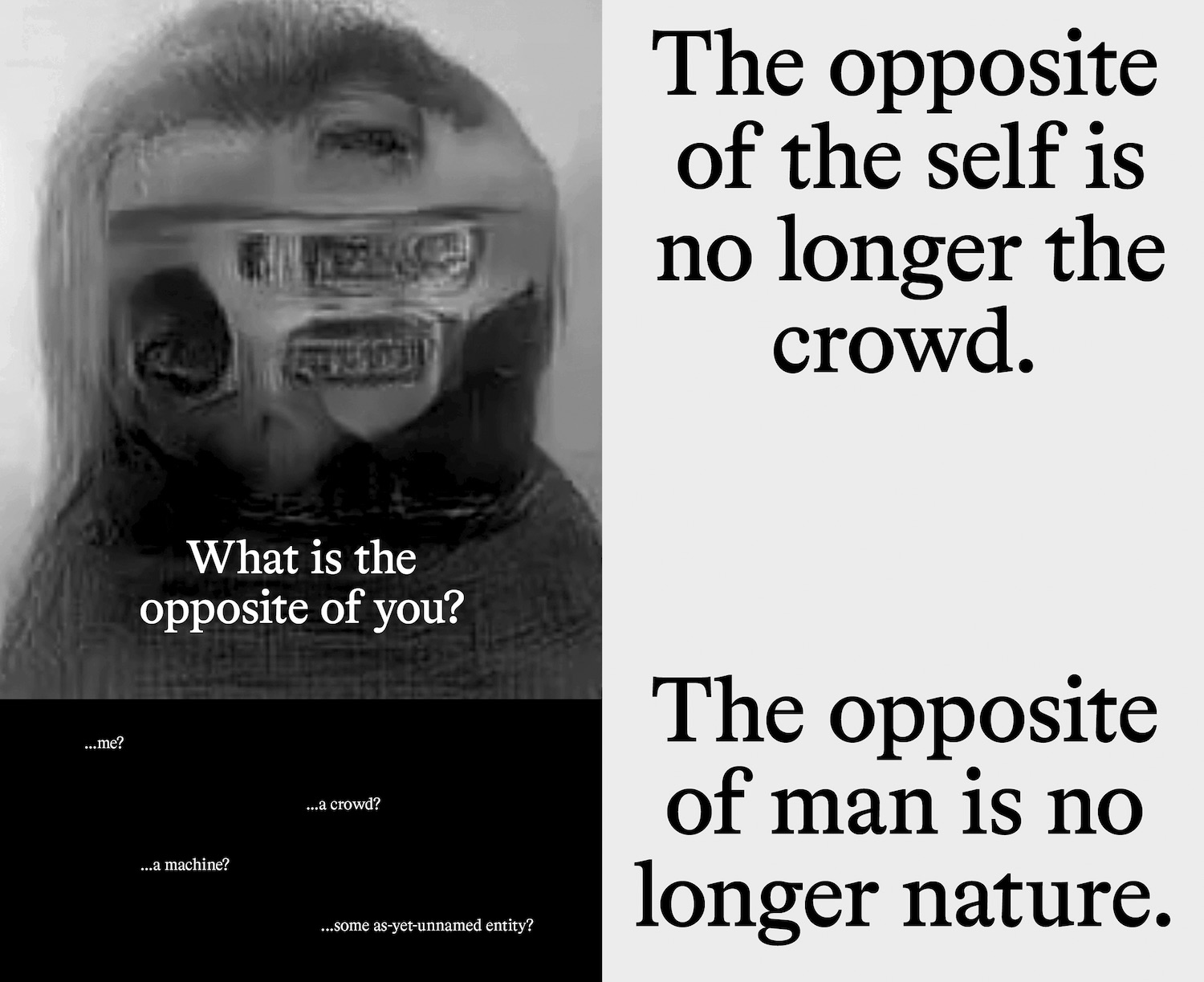

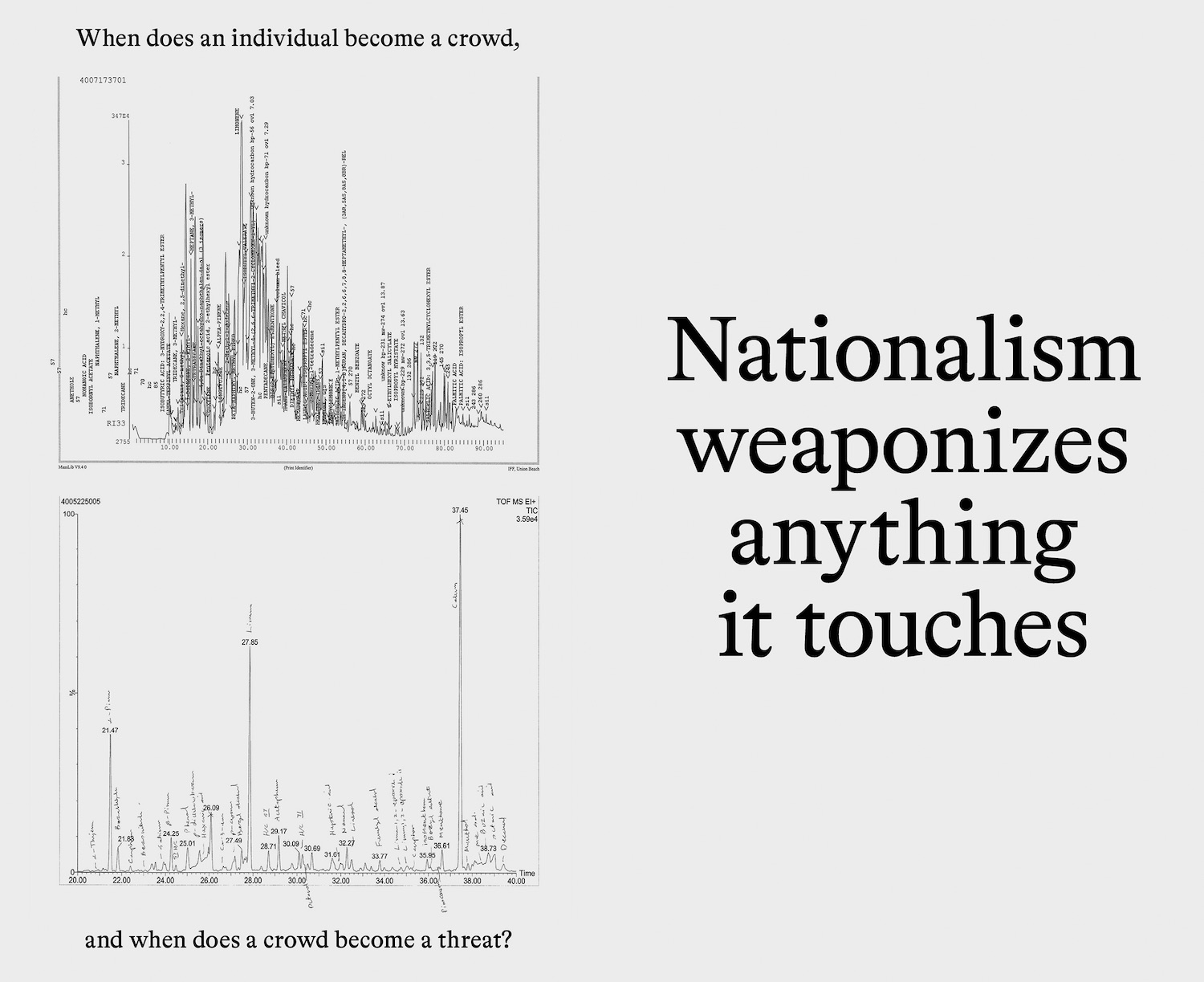

This question — what matters more, the individual or the crowd — is always at the core of political upheavals. 2016 was no different. Brexit. Trump. However, now, as we enter the Early Coronacene, when COVID-19 suddenly made at least a third of the planet socially distance and emptied cities out for some time to come, the meaning of “an individual” and “the crowd” has morphed yet again, in ever-more-extreme ways.

HUO: Doug, what is happening to the individual? Socially, technologically, philosophically?

DC: I think the sequence is that technology changes the person, and then those changed persons collectively, consciously or unconsciously, create philosophy. The evolving global philosophy disproportionately seems to favor US-style libertarian thinking as well as magical thinking. Tech also seems to make people believe they have more agency than they actually have, so it brings out the worst in them because most people want power, and if they see a possibility of getting even the tiniest amount of it, they’ll usually pounce. Technology creates astonishingly granular feedback systems for calibrating (perhaps meaningless) individual power statistics with likes and views et al. So, everyday life for the individual becomes an arena for monitoring, creating, and reinforcing stats.

HUO: Black Mirror did that wonderful episode with Bryce Dallas Howard on this. “Nosedive.”

DC: I loved it! And thinking on a larger scale, the Chinese government is betting the farm on social credit scoring. I do think people living in, say, twenty years from now won’t believe just how quickly “the center” vanished from our cultural lives and collective philosophy. It happened in one year starting in mid-2016. I find if you ask people, 2016 was the worst year ever. Somehow, to me, even 2020 doesn’t feel wretched the way 2016 did. Our biggest collective philosophical sorrow is that the center is never coming back. How will you even explain “the center” to people born in 2020?

SB: If you were to ask me which was worse: well, my soul felt attacked in 2016, but, my body didn’t: I could still move, meet, greet, explore, and share my PTSD with others directly, and in multiple places across earth. In 2020, it’s my body, all of our bodies, that’s the target. However, COVID-19 doesn’t actually “want” anything, certainly not our souls. My lifestyle — and the lifestyles of the professional worlds we inhabit — is potentially going to change more tangibly in 2020 and 2021 than it did in 2016–17. In that sense, it feels more catastrophic to me personally. Geopolitically? That’s another conversation.

HUO: How would we define “the crowd” in the era of the extreme self?

SB: Maybe we have to go backwards first. One of the hallmarks of modernity for Charles Baudelaire in the nineteenth-century city was the ability for an individual to melt into mass crowds. Anonymity became a core facet of identity.

DC: I love that.

SB: This is ever truer for the anonymous individual in a virtual crowd. Digital anonymity provides an impunity that empowers armchair trolls in the comments section. Such anonymity turns the craziest conspiracy theorists into major media players who now have hotlines to the Oval Office in the Whitehouse. “Drink bleach. It will make you immune!” And, you know what? People did drink bleach. That’s how powerful untruths are today, when consensus-based reality has been dismantled.

HUO: Before COVID-19 arrived, the three of us had been thinking mostly about these kinds of distributed, dematerialized crowds. The “crowdsourced” crowds.

SB: The three billion and counting TikTok views of Drake’s Toosie Slide.

DC: Three billion? That’s humbling.

SB: Maybe it’s like this? In the 2010s, first there was FOMO, the fear of missing out. Then came JOMO, the joy of missing out. In the 2020s, we are now entering a new FOGO, the fear of going out. Some people are going to suffer from that. While others are just going to YOLO [you only live once] the end-times.

HUO: Yes. These last few months, we have all been processing what it means to be part of virtual crowds instead of physical crowds. The two will keep synthesizing into a new collectivity. And a new alienation. Physical distancing has made us want to connect with each other even more. As I have been saying recently, NO ZOOM NO CRY.

SB: We just need the technology to catch up to our next realities. A bad or no Wi-Fi connection means you’re uniquely isolated. Good Wi-Fi becomes a basic human right.

DC: I have this saying that you can’t use old technologies to fix problems created by new technologies.

SB: Amen. It does feel that one of the biggest near-future casualties in the Early Coronacene will be physical crowds. Does anyone know if a gathering of more than two people constitutes a crowd now? Five people? Five hundred? Will Tokyo 2021 be the first post-audience Olympics? If art biennials measured their success by startling visitor figures, in the hundreds of thousands, but those kinds of densities are turning into virus nightmares, can large-scale cultural events still survive? Crowds are about to be associated with mortal anxiety for some time. It’s as though Elias Canetti’s famous book Crowds and Power (1960) will need to be revised as Crowds and Fear.

HUO: Let’s imagine it’s the year 2030. What is the biggest change that happened to individuality in the preceding decade?

DC: I think the biggest change will be the inability to handle or exist inside the physical world. For decades in Japan they’ve had a demographic called hikikomori, and there’s over a million of them. According to Wikipedia:

Hikikomori are reclusive adolescents or adults who withdraw from society and seek extreme degrees of isolation and confinement. Hikikomori refers to both the phenomenon in general and the recluses themselves. Hikikomori have been described as loners or “modern-day hermits.” Estimates suggest that half a million Japanese youths have become social recluses, as well as more than half a million middle-aged individuals.

The only time hikikomori ever leave the house — if they do — is in the middle of the night to maybe go to a 7-Eleven or a Lawson for snacks. The “real world” no longer exists for them. Being hikikomori is like anorexia or hoarding in that once the tendency is in operation, it’s already too late to fully rectify.

SB: There was a meme that emerged when COVID-19 reached the Western hemisphere. It said — and here I paraphrase — that with everyone in the world shutting themselves indoors, all the hikikomori can finally go outside.

DC: No! It’ll be the opposite! But, okay, here’s a thing. I know that the “virtual world replacing the physical world” is a very old idea, but if you’re asking for a visual of life in 2030, then I think that’s going to be it. The people who are going to enter a state of permanent isolation are probably the same people who won’t stop wearing masks when a vaccine to this wretched ordeal is deployed. We’ll have to wait and see.

HUO: I hate waiting.

DC: We’ve all grown so impatient, haven’t we? Thank you, internet.

SB: I miss my pre-Corona brain.