Mies van der Rohe’s idea for the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin was based on an earlier project for which he conceived of a space where the “barrier between the artwork and the living community is erased” and the works become “elements in space against an open and ever-changing background.”[1] Such ideas are remarkably close to the Brazilian artist Lygia Clark’s innovative practice, which sought to disrupt the distinction between artwork and space, while equally redefining the relationship between artwork and viewer. This creative affinity remains unstated by curators Irina Hiebert Grun and Maike Steinkamp, but it sits thoughtfully in the background of this major retrospective of Clark. The glass pavilion’s usual challenges — endless daylight, lack of walls, and its scene-stealing beauty — here serve only to enhance the exhibition’s chronological unfolding, providing the perfect backdrop to appreciate Clark’s deeply enthralling and radical work.

The first part of the exhibition is largely devoted to Clark’s works of the 1950s. Her earliest geometric abstract paintings reveal initial close ties to the concerns of European Concrete art — where shapes, lines, and planes of color intersect across canvases. In works such as Composição (1956), light and space penetrate the grid to create illusions of three-dimensionality. They reveal how from early on she used various gradations of color to play with sensory perceptions, foreshadowing her later “Objectos Sensoriais (Sensorial Objects)” (1966–67). In 1954, she developed her concept of the organic line, which set forth a radical new path in her work. The organic line was the beginning of a three-dimensional articulation of space — a physical and conceptual opening or small gap within the surface of the painting, where the objective became “to express space in and of itself, and not compose within it.”[2]

69 × 82 cm. Courtesy and © Cultural Association The World of

Lygia Clark.

Keen to emphasize the importance of architecture in Clark’s thinking, there is a section devoted to its occupation. Models show imagined interiors where abstract paintings become openings to be permeated. Construa você mesmo seu Espaçopara Viver (Build Your Own Living Space, 1955), whose modular design strikingly echoes the Neue Nationalgalerie, features moveable walls, creating a dynamic space where art and living coalesce. Such openness is carefully reflected in the exhibition design which, despite containing walls, feels light and airy. This creates beautiful sightlines between works from differing phases, all of which illustrates how Clark’s work conceptually advanced toward her complete fracturing of the picture plane and into her organic sculptural abstractions, “Bichos” (Critters, 1959–63) and “Trepantes” (Grubs, 1964–5), that visitors encounter next.

From 1959 — when she co-founded the Neo-Concrete Movement, which emphasized art as an organic, sensorial phenomenon — to her death in 1988, Clark pursued a practice that was increasingly dedicated to sensory and experiential encounters. The “Bichos,” for example, are small “living” mutable sculptures with hinged aluminum plates that can be endlessly folded into varying arrangements. Here, she transformed the audience into active “participants” (her preferred term), and later through her “propositions” she identified that “the work is the act.”

This latter half of the exhibition — where replicas allow you to fully engage — is a joyous journey through Clark’s reimagining of art’s political and social potential. The “Objectos Sensoriais” (Sensorial Objects, 1966–67) engage our sight, touch, hearing, and smell in both natural and absurd ways. Metal goggles reflect your gaze back at you, textured gloves alter how you feel objects, rubber tubes create strange noises, and smells tingle our noses. It is a lot of fun to play with these artworks in the museum setting, and to observe others smiling and laughing as they do the same, but they also operate on a more serious level. The intense bodily awareness they foster was part of Clark’s belief that art was a liberating force against oppression, set against the backdrop of Brazil’s then military dictatorship.

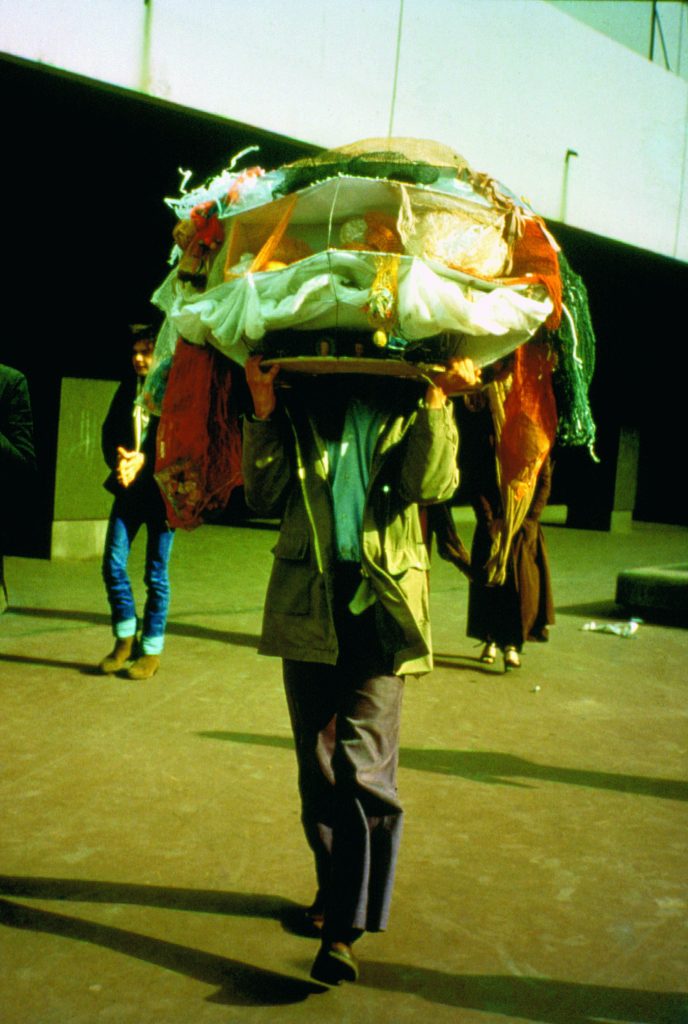

As intimate interactions and collective experience became increasingly important to Clark, she developed her “Arquiteturas Biológicas” (Biological Architectures, 1972–76), which encourage people to take part in community-building actions with materials such as rubber nets, plastic film, and saliva-covered thread. Activated by “performers” at set times, these are less performances (as they are advertised) and more demonstrations — opening up participation to whoever is willing, which included many people both young and old while I was there. In a moment of beautiful symbiosis (only possible in a space such as this), during an activation of Estruturas Vivas (Life Structures, 1966) — where a group are tangled up in a net of rubber bands and move as a “Collective Body” across space — a group of teenagers rehearsed a dance on the terrace outside the window.

Clark’s final phase — which witnessed her developing a therapeutic method that used art to heal — has often been portrayed as her abandoning art altogether (her 2014 MoMA exhibition was titled “The Abandonment of Art,” for example). This exhibition firmly counters this by presenting it as the natural conclusion of her dedication to art as a social practice.

Clearly curated with both care and conceptual rigor, this exhibition succeeds at proving Clark’s status as an important visionary artist in the history of modernism. I left feeling both sensorially and intellectually enriched. If anything disappoints, it’s only the exhibition’s rather bland title.

Lygia Clark.

[1] Phyllis Lambert, “Foreword: Space and Structure,” in Neue Nationalgalerie. Mies van der Rohe’s Museum (Berlin: Deutscher Kunstverlag Verlag, 2021), 17.

[2] Lisa Gabrielle Mark, “Lygia Clark,” in WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution, ed. Lisa Gabrielle Mark (Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press, 2007), 224.