Klaus Biesenbach: Your visual arts career is your second successful profession. Why did you decide to not pursue your promising musical career?

Jeremy Shaw: At the end of 2009, after touring in support of an album for most of the year, I felt I had hit a wall with what I was able to do in my position in the context of the music world, and at the same time was feeling a huge amount of possibility with ideas around my visual arts practice. I used to keep the two worlds quite separate, but since making the decision to focus on visual art exclusively, music has become much more integrated into my work, both as a subject and element.

KB: What is the role of music in your art?

JS: It varies — sometimes I score video and film works specifically with my own music, or using elements or quotations from other people. In this capacity, I really aim for it to further the conceptual layering of the work, rather than just embellish it as a traditional score would.

KB: Which works show this quality?

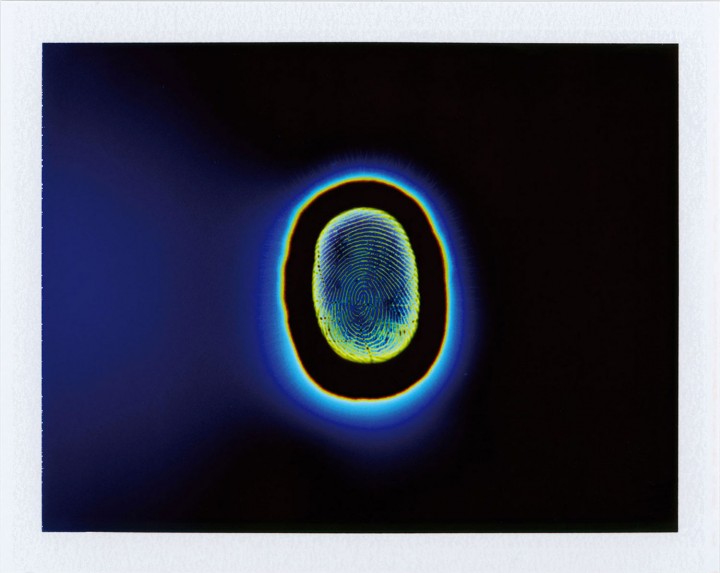

JS: In Best Minds (2007-11) I used a similar style of composition to that of William Basinski’s Disintegration Loops in order to reference dying analogue technology and trance — but using source material that partially comes from the subjects of the video, before processing. In other works, music has been the basis of the conceptual strategy without actually being present in the final piece, such as Transcendental Capacities (2010), where I listen to music widely considered “profound” while using Kirlian photography to measure changes in my aura — the result being scientific-looking Polaroid pictures of my index fingerprint titled after the song in question.

KB: When talking about Best Minds we also came across Gaspar Noé’s Enter the Void. Who influenced who here? Between his movie and your DMT experiments?

JS: Well, I gave him his first hit of DMT! But he was already working on Enter The Void when we met at the opening of my DMT exhibition in Vancouver in 2004. He was there location scouting for the film, and had tried Ayahuasca, but not DMT yet. So we hung out a bunch and one night I gave him a dose at his hotel. I’d already finished working with the drug when we met, so Enter The Void wasn’t an influence on my work at all, but I think he did an amazing job at illustrating what my piece left purely to the transcriptions.

KB: Your work often is about altered states from substances — or the lack of substances, pure trance. Does this come from addiction or abstinence?

JS: It can come from both I suppose, although I tend to not be all that interested in drugs that are synonymous with addiction. I grew up in Vancouver, where heroin has always been a massive problem, so I had an aversion to it and it’s trappings from an early age. I’ve always been much more drawn to psychedelics — substances that incite real altered states, but ones that don’t necessarily need to be revisited. With abstinent behavior and the altered states — with straight-edge hardcore, or religion, or meditation, etc., I think that often becomes a type of addiction, or compulsion.