An innumerable amountof sheets, coherent sequences of pages filled with sketches, notes, fragments of texts, recorded on graph and typewriter paper, numbered and collected in notebooks, calendars, files or boxes, individually framed and hung en bloc or published as a book or catalogue: Hanne Darboven saw herself as a writer rather than a visual artist: ‘I see myself as a writer, which I am, regardless of what other visual materials I may use. I am a writer first and a visual artist second.’

Hanne Darboven, certainly one of the central figures of Contemporary Art in Europe and internationally, died in March 2009 in her home, Am Burgberg, the name of a small cobblestone paved road in Hamburg-Harburg, a suburb of Hamburg, aged 67. Originally born in Munich, Darboven, who was a scion of a coffee trade-dynasty, spent her childhood and student years in Hamburg, studying at the Hamburg College of Art, before she decided to go to New York during the mid-1960s where she stayed for two years. Hanne Darboven is generally considered to be a conceptual artist. In fact, the development of her oeuvre must be seen in the context of the advent of American Minimal Art and Conceptual Art. After a brief geometrical phase in Hamburg, and inspired by her last academic teacher at the Hamburg Art College, the Brazilian op artist Almir Mavignier, it was in New York that Hanne Darboven found her characteristic drawing and writing ‘system’: ‘In New York, I tried to find something that I could work on for my whole life. New York was where I built my work.’ Being in close contact with the new movement of Minimal and Conceptual Art, with artists like Sol LeWitt, Carl Andre, Joseph Kosuth, Mel Bochner, the American critic Lucy R. Lippard, the art dealer and curator Seth Siegelaub and gallerists like Leo Castelli and Konrad Fischer, she felt understood and encouraged to exercise ‘her lifetime duty’.

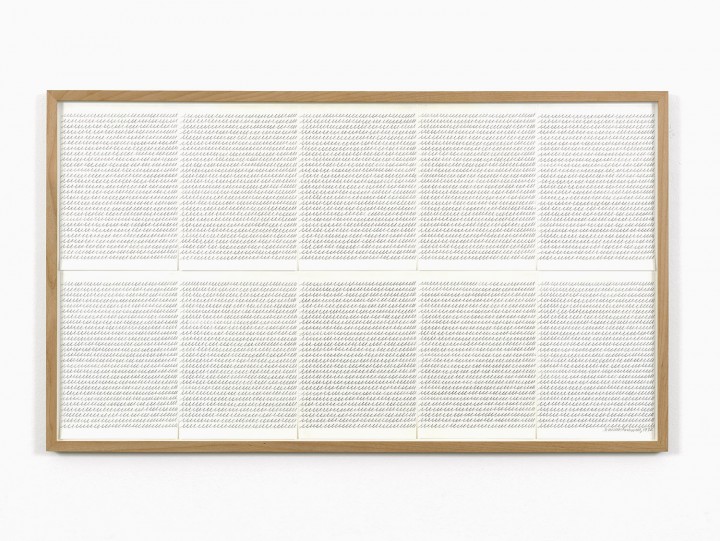

‘I only use numbers because it is a way of writing without describing … It has nothing to do with mathematics. Nothing! I choose numbers because they are so constant, confined and artificial. Numbers are probably the only real discovery of mankind. A number of something (two chairs, or whatever) is something else. It is not a pure number and has other meanings.’ Conjoining a rigorous numerical process to free associative roots, and tight rational thought to intellectual freedom, this capricious sense of time has resulted in diverse monumental works, which may span a month, a year, even a century. In New York, Darboven started by making abstract, geometrical drawings on graph paper, continuing with calculations and series of numbers and using the date as a basic unit of her system of numbers, calendars and, later on, her time-based writings. It was during this first period in New York, when she visited the first exhibitions of Minimal and Conceptual Art, that her rigorous and prudish artistic practice was noticed and recognized for the first time.

It is Darboven’s complex system of writing which for the most part forms the framework on which her whole oeuvre is built. Usually both numbers and script have a subordinate function — they are subsidiary to the information contained in them. Darboven, however, sees them as a visual medium.

She employs the written picture itself — that is the figures and texture of the script. Darboven sees writing simply as an operation that takes place according to strict rules, in a manner reminiscent of the mechanization of the art production process in Concrete Art and Minimal Art. The serial repetitions, variations and accumulations of numbers, texts and undulating lines in Darboven’s work articulate a rational structure that is seemingly mechanical in origin. This rational structure has no beginning nor end, and unfolds with an impersonal and rational regularity. This allows Darboven to ‘scribe without describing’ — that is, without communicating any meaning other than that of the figure or written picture: ‘Texts can also be accommodated by this approach, allowing them to be rendered in a concrete way.’ Hanne Darboven did not accept to call her books artist book. For Hanne Darboven, the medium of the book was an equivalent of the work itself made in a more concrete way, as one of its possible materializations. It was in1968, in the year when Hanne Darboven had come back to Hamburg right after the death of her father, that she published her first ‘book’, titled: 1969–77. New York. In 1971, at Konrad Fischer Gallery in Düsseldorf, Hanne Darboven decided to present again the sheets collected in files in shelves like in an office or as an archive which could be used by visitors. When asked how she wished her works to be read, she replied that there is always a beginning and an end point, but that the viewer is not forced to respect these — it is up to the individual visitors to read the artwork. Alternatively, ‘they can just look’. Hanne Darboven had her first own book published as an edition for which she chose a number of sheets of a work to be published as a catalogue. Starting from the late ’80’s , Hanne Darboven published almost all of her works exhibited in institutions and galleries in form of a book as well, showing the complete number of sheets of each work. From then on, the artist published her own catalogues in this manner for almost every exhibition. One could even say that the installations en bloc of the single files framed individually and covering the walls in grid-like structures, could be read as books, one after another in a certain order, numbered and followed by the reader who is in this case the visitor. Instead of offering installation-views of the exhibition and texts by critics and curators, she would rather select a certain number of sheets of the work, in order to publish the work itself in the form of book, designed by the artist herself. For her exhibitions, Hanne Darboven mostly devised the catalogues herself, using the book as an independent art form: designed from beginning to end solely by the artist herself, it contains no introduction nor explanatory articles about the work, but is a work in itself, a reading book.

Hanne Darboven wrote by hand, copied different kind of texts by transferring them into her own handwriting. Only in few cases would she have them copied by someone else with a typewriter. This personal aspect of her art-making is reminiscent of the practice of monks in the Middle Ages, copying the texts of the Bible day after day, writing the codex, and this is rather a contrast to the idea of the depersonalized primary structures of the prefabricated or mechanically created, mainly geometrical forms, being used by the Conceptual and especially the Minimal artists of the time. Darboven chose the medium of the book as the classical medium of knowledge of the early modernism, constructing a personal reading of history and time. She practiced cutting fragments of encyclopedias, literature and later of articles out of magazines and newspapers, transferring them into her own handwriting and combining them to form a new text, a privately hand written ‘cultural history’.By this token, Darboven’s different modes of presentation have a conceptual meaning, and are her way of reflecting the specific nature of the media and the historical cultural coding in her artworks — by presenting them variously as scripts, in book form, as installation displays, as film projections or as musical compositions. In her works, the writing is both a reflection and a concretization.

The character of all of her written works (scripts) clearly demonstrates that Hanne Darboven took the book seriously as a cultural vehicle of ideas, thoughts, as well as traditional and contemporary matters, quoting more and more literary texts and fragments of encyclopedias as well as history books, but also everyday messages, like headlines of newsletters and magazines, calendars, postcards, Sammelbilder and advertisings. For her written oeuvre Hanne Darboven took the structure and composition of the book from the classical structure of the book, consisting of the front page, the title, the contents, the preface, the main part, the epilogue and the index. It is typical for her work that she would integrate the conventional terms and composition of a book into her works, quoting terms like Prefaces, epilogue, plate, page, but also grammatical signs such as ‘semicolons, ‘slashes’ (‘–’) or other signs or marks and structuring terms concerning the syntax of a sentence or the structure of a book, such as the ‘index’. In connection to her work, the term ‘index’ includes both the reduction and logical structure of her conceptual art as well as the semiotic reading of her scripts.

The term ‘index’ mainly has two meanings. First, the index of a book as an alphabetical listing of names, places, and topics along with the numbers of the pages on which they are mentioned or discussed, usually at the back of a book. The index can consist in a sequential arrangement of material, especially in alphabetical or numerical order, or a kind of guide or standard, indicating the relation of one part, thing, or topic to another with respect to size, capacity, or function. It can therefore be seen as a compressed form of an encyclopaedia or as the structure of another system of knowledge. Secondly, the instructive character of the index (Latin: ‘pointing finger’), means that an index ‘indicates’ something: for example, a directional signpost, a sundial or clock ‘indicates’ the time of day. A map is indexical in pointing to the locations of things, an indexical sign is always connected with the cultural and conventional context and stands for something, pointing out something else.

Hanne Darboben often uses calendars, texts and imagery from all different kinds of contexts and sources, transforming them into a constructed pseudo-system consisting of lists, calculations, quotations, comments and collages … The encyclopedic idea of collecting and defining the whole knowledge of humankind dates from the time of the Enlightenment at the beginning of modernity. The encyclopedia worked as a summary, and stood on the one hand for a philosophy of rationality and control of the world by mankind, and, on the other, for transparency, for public and free education and the politically mature citizen – treating equally all fields of science, knowledge and handcraft, against elitist convention and hierarchies. The index of the encyclopedia or scientific books finally functions as an orientation guide to the structuring of the complexity of the world in a logical, alphabetical order. The function of the indexical signs can be explained by ‘shifters’ in linguistics (such as ‘here’, ‘there’, ‘I’, ‘you’) which depend on the situation. At first sight, the relationship of Darboven’s indexes to the works is more like that of the index to a book. Furthermore, the character of her scrips itself can be understood as a recapitulation and summary of motifs, being repeated constantly throughout her works like in musical compositions. The serial repetitions, variations and accumulations of numbers, texts and undulating lines in Darboven’s work articulate a rational structure that is seemingly mechanical in origin. This rational structure has no beginning nor end, and unfolds with an impersonal and rational regularity. In some of her works, Hanne Darboven replaces the letters by numbers, calculations and summaries of the dates listed in form of the ‘K-Wert’ (‘Kvalue’ ), or the listed terms and words, or the whole text by lines and waves. Darboven’s artworks, with their graphical, gestural undulating lines and letters, differ from Concrete Art, Minimal Art and Conceptual Art in that they are created by hand. In this, they could be said to hark back to the European Christian tradition of the written chronicle.

The emphasis here is on the doing, on the activity of writing and its physical consummation.In this context, the script of Hanne Darboven functions as an expression of thought itself, as ‘an opaque, wandering and sometimes even unreadable trace of thought’.Finally, Hanne Darboven’s main subject is the visualization of temporal process: Hanne Darboven writes rows of time, works equally with imagined and real (written experienced) time. In other words, although her works are described as constructions drawings they are expressions that refer to statistics and are to be understood as temporal processes. Given their temporal character, they are closer to the time-based media, literature, films and music than the visual arts. And yet, they differ decidedly from the latter time-based media in that they can be looked at and experienced visually, and also in their ‘style’ in the artist’s personal handwriting, which is an important part of these works. For the work Wende 80 Darboven for the first time transformed her numerical system in music. Writing, like music, is a form of time-based art ‘par excellence’. The only moment that seems to be fixed in time, and in the present, as constantly disappearing, are each accompanied by the preemption of what is to come and the past as something that always lags behind, the one resembling a prefix, the other a suffix. As in the act of writing and reading, with each note we contextually hear what went before and comes afterwards as the prefix and suffix that are always implicit. This synchronism of times in Hanne Darboven’s recordings and notations is similar in both conceptual and formal terms to the polyphony of a score.

Hanne Darboven counts time, ordering, contracting, and expanding it, whether in her constructional drawings, date calculations, her writing or musical scales: ‘One+one is one two. Two is one two. This is my original thesis for all rules, which proceed in a mathematical way. I am writing mathematical literature and mathematical music.’