What does a thing know of its own production? The language here isn’t mine, but rather comes from the title of a recent work by the New York–based Croatian artist Dora Budor (b. 1984). I’ve turned her title into a question. The work that it refers to (What Does a Thing Know of Its Own Production, 2016) is a kind of sculptural relief incorporating a disarray of materials: laboratory glassware, cement, silicone tubing, rocks, resin, soil and other similarly brown, earthly colored things making their way into what looks like topsoil taken from some far-off, dystopic junkyard. All of this is wall-bound and framed in an elegant stained walnut — a sculpture in the drag of painting. Most prominent in the display is a large scrap of prosthetic flesh, a blooming wart in the lower right-hand side of the muddy stream. Reading the materials list for the work you might learn that the flesh, unconvincing but evocative in form, is zombie skin taken from the schlocky, mostly derided (but commercially successful) sci-fi horror film Underworld: Evolution (2006). Like much of Budor’s work, the piece is an example of her reanimation of Hollywood film props sourced from memorabilia and collectables dealers. So often central to these wall-bound and free-standing sculptures, various special effects props and architectural models previously used in film productions are acquired by the artist and elaborated into something quite different than (but aware of, in touch with) their former screen destinies. The composition — which is based on a heart-lung machine diagram, a medical device used to sustain the body during open-heart surgery — calls to mind familiar systems and narratives. In it we see an ecology shaped by human endeavor, the folly of technological ambition and the tension between the organic and inorganic. But what to make of the skin prop’s past life and its relation to its present reality?

At New Galerie in Paris in early 2015, Budor presented Mental Parasite Retreat 1 (2014), by now one of her more well-known works. A freestanding sculpture, it consists of a cinema chair reupholstered with silicone and implanted with a prosthetic cyborg chest in its center. Within it, an unseen animatronic device creates a subtle motion. The chest prop is from the American science-fiction film Surrogates (2009) — a thriller, starring Bruce Willis, based on a comic book about a near future in which people live vicariously through immersive, remote-controlled robot avatars. For a film with an eighty-million-dollar production budget, the leading man’s prosthetic that Budor has buried in her work looks rather modest — the kind of thing you might expect to find in a high-end costume shop. But herein lies a truth about film production’s increasing immateriality. The special-effects prop is more and more akin to a rough sketch in a film’s genealogy, a kind of material starting point that’s later refined and sutured into the final work during the heavy lifting of digital postproduction. These props, then, share a common ramshackle materiality: they are things that were never meant to persist in their thingness. Before they find their way into Budor’s sculptures — that is, in production and on the screen — they are objects (or lenses) through which we see and make sense of the cinematic narrative. In both design and manufacture, the props are intended to be photographed and discarded, to be incorporated fully into the shadow world of the movie screen as images without a referent, what Derrida might call ghosts. Outside of the image they become something else. Like the cinema chair itself, usually cloaked in the darkness of the theater, the prop referent of these images often relates to our own bodies — which, again like the cinema chair, we readily use without noticing or contemplating. It’s a fact not lost on the artist, and certainly not unrelated to her process. In her operation of dislocation, she renders her source material awkwardly incomplete and highly conspicuous. Rather than simply collecting them as bits of Hollywood fiction, Budor seems to instantiate a desire to inhabit their decrepit insufficiencies. To understand something of the use trajectory of these props, imagine, for a moment, the desperate world of the unnoticed throwaway — the plastic fork shoved into your Chinese takeout bag, the disposable headphones handed to you by a distracted flight attendant high on Xanax.

If you were to try and identify a definitive trait of experience under Western technocratic capitalism during the past decade, you could do worse than talk about images. Images, in a sense, are the things that bind individual experience most closely to the increasingly networked economies of surveillance and exchange that shepherd us through daily life. They are the postproduction of the everyday, what sutures the rough sketches of our lived reality into the sensible narratives from which we derive the pleasure and purpose of our public selves. In this regard, the digital image has firmly ensconced itself in the constitution of post-Internet selfhood. To be a person today, especially a person of a certain age or generation, is to project images of yourself onto the world — at least that seems to be the case for now. If we accept this assertion, its dialogic extension becomes one in which experience is increasingly guided by the future point at which it becomes an image. Much of Budor’s output over the past few years has focused on several related ideas of projection. In many works, she enacts a kind of reversal of the material film prop’s projection into the phantom image narratives of Hollywood fantasy, taking them out of this orbit and reinserting them into the dense materiality of her sculptures. Likewise, she models Hollywood’s forward projection in the imagined futures of the science-fiction genre in many of her works.

Consider Budor’s photographic suite When the Sick Rule the World, Conference of Psychotic Women and Allergic to the 20th Century (all 2015). In these three works we see a type of cool but deeply saturated shallow-focus photography that could have been lifted from The Bourne Identity or a similar thriller. The photographs actually are inspired by Robert Altman’s 3 Women (1977) — all feature a single figure in the shape of a tall, slender female. She wears unremarkable streetwear in gray, black and white. Her body is youthful and attractive, always alone, and moves through nondescript urban environs. Her face, however, is at a disjuncture with her body, inundated with patently artificial wrinkles, the battered skin of a woman deep into advanced age; her hair, likewise, is a strung-out and dusty gray. In the photographs, she seems like the target of surveillance. She is self-aware as she moves through the city, in some instances warily studying the landscape about her, though never locking eyes with the camera that peruses her.

In 2015, Budor’s work was included in “Inhuman,” a group exhibition at the Fridericianum in Kassel, Germany. Curated by Susanne Pfeffer, the museum’s director, the show presented the work of a number of artists who imagine the human figure diverging from socially or biologically determined destinies into sometimes monstrous formations. Budor presented several works in the show, not least of which was a new series titled “The Architect.” These were screen-like wall works made from metal frames and semitransparent silicone sheets. On the silicone sheets were compositions of SFX transfer scars used in the making of 300: Rise of an Empire (2014), the sequel to the fantasy war film 300 (2007). Budor further adorned these screens with her own electrical fuse boxes, stainless-steel conduit, silicone-cast wiring and electrical fittings — all stuff that anchored each work to the architecture of the museum’s exhibition halls, making them prosthetic outgrowths of some internal biology of the historic German institution. The resulting forms, with their cold stainless steel and spills of fake blood, call to mind some transitional fantasy tech hybrid between a flat-screen television, a malfunctioning light box and a medical gurney — all devices before which (and on top of) human bodies come to rest, to look, or to die. The body scars from the 300 sequel push the work toward a weird, disjunctive untimeliness. The original 300 film, in all of its vulgar American chauvinism, captured rather distinctly the bellicose and fascistic energies of a collectively hallucinating nation at the tail end of the Bush era — and it reaped in box office revenue close to half a billion dollars for its success in playing to the national mood. Its deflated sequel, on the other hand, was a more costly and less successful spectacle. It had much less traction at the moment of its making; it lacked the overwhelming vulgarity that made the original such an odious marker of its time. The scars in Budor’s work were created to adorn the porny, muscle-bound fantasy bodies for which the 300 franchise is known. Now on her hospital flatscreens, these artificial scars evoke that body in absentia — but is it the human body in the cinema hall or the bodies portrayed on the screen? In a way, Budor’s strategy mimes the work of the prostheses that form the bedrock of cinema’s special effects: she evokes the image’s insufficient material origin in order to turn back the clock and allow its chromosomal blueprint to evolve into something divergent from its original screen-based destiny.

Though the 300 films are fictions under the rubric of fantasy, most of Budor’s film references, both in her work and in interviews the artist has given, are science fiction. The two genres are first cousins of course, sharing a common trait in their projections through time. While fantasy war porn like 300 projects post-9/11 American jingoism into some imagined antiquity, it says more about the moment of its making than about anything that came before or after it. That fact resonates distinctly today, on the verge of an American election in which the political discourse from the right continually gestures toward a glorious past that must be restored. Science fiction also performs this type of projection, but in the other direction, into the future. Like fantasy, it fixes the work of fiction to the era of its origin by articulating that era’s fantasies about the future. This temporal displacement, so often central to both genres, is a familiar current in Budor’s work.

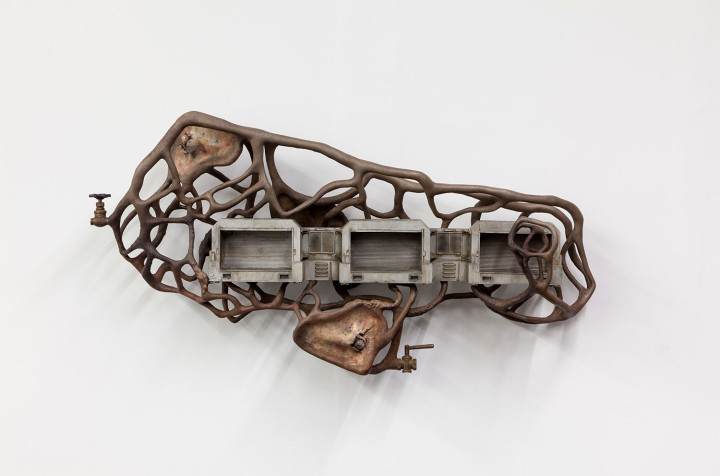

An important motif relating to projection in the artist’s practice — both methodologically and materially — is the architectural model. Models have appeared in Budor’s work numerous times, often with organic-seeming outgrowths that frame her cinema relics with a rusty patina. In Slow Ticking of a Callous Mind (2015), we see one such architectural model depicting a city rooftop used in the production of Batman Returns (1992), an urban fantasy adventure trapped in a kind of permanent night, in which Batman leaps across such dilapidated structures and restores order to a world where a failing state cannot. Turned on its side, the model’s triangular geometry is made into something of an arrow sign, the referential becoming graphic. The beautifully weathered and intricate details of the model invite a leaning-in on part of the viewer — a reverse projection. This work is all about size: the size of the sculpture in relation to the size of its beholder, the virtual shrinking it seems to solicit when apprehended as a set ready to be inhabited. Captured on motion-picture film, this same rooftop is transposed by light and scaled beyond its celluloid confines to create a giant cinema image. Through the superstructure of film editing and superimposition, the material becomes virtual in terms of its limitless potential for scaling and projection. Budor’s sculpture seems to challenge us: Can we, personally saddled as we are with all of the technological powers of outward projection and reach, do the reverse?

In the spring of 2016, Budor presented an ambitious new work at Ramiken Crucible in New York. Here, her former hobbyhorse strategies of projection, reanimation and prosthetics were set in a kind of tense, bullying proximity to each other. The exhibition “Ephemerol,” named after the experimental drug in David Cronenberg’s movie Scanners (1981), featured a single work whose title is too long to print here. Budor had scaled her work up for the show, moving closer to the grandeur of the cinematic image and, maybe for the first time, requiring viewers to circle around the work in order to fully experience it. Not having read about the piece before I went to see the show, my first few minutes with it were lost in a kind of hazy abstraction. Because the work occupied so much of the gallery’s modest floor space, I had failed to see the (later) clearly discernible face on the giant head she had created out of semitransparent resin — an inversion (mold versus cast) of something that appears in Cronenberg’s film. Inside this mold, I also failed to make sense of the undulating forms that mimic some ’70s utopian furniture design, literally turned on its side. The seating modules inside were, in their original design, intended for human bodies, of course — they constitute a living environment, however reconfigured it might be here. Consequently, the piece made me aware of my own bodily envelope like only a recent doctor’s visit had. Later, I remember reading something in which a New York critic had challenged Budor’s work on the grounds that, while interesting, it perhaps did not surpass its cultish subject matter (Cronenberg’s film). Finally, I thought, it was in this critic’s slight misreading that the artist meets a challenge worthy of her abilities. Rather than reshaping the film narratives that inspire her, she was attempting, rather, to reverse the operations of the cinema apparatus, that which fashions so much of our longing for the transformation of the present.