Cyprien Gaillard is no studio artist. He wanders and finds things. In Munich, he explored the Haus der Kunst, sometimes late at night. The building, completed in 1937 — its archives, basement, stairwells, and polished red sandstone — became his material. For the show “Wassermusik,” he added little: a stereoscopic film, sparkling water (Vichy, a reminder of fascist entanglements between Germany and France), and small flasks of Jägermeister. But he took much from the building.

When Gaillard first came to Haus der Kunst, he was drawn to the ammonites visible in the floor of red Saalburger Marmor, like ornaments by a non-human architect. These are shells that lived here millions of years ago, when Central Europe was underwater. Gaillard is interested in deep time — from fossils to fascism. He’s drawn to marble’s seamless slabs, and their cracks and fragments.

“Wassermusik” unfolds from a lofty stairwell of the Munich institution. It is an attempt to negotiate his relationship with the building — a mix of veneration and repulsion.

The first installation, Wassermusik I (2025), contains no direct reference to George Frideric Handel, but plenty to water. Gaillard replicated the ceiling tiles, adding brown, painted lily-pad-like trompe-l’oeil stains, and placed artificial light behind the faux skylight, creating an atmosphere of permanent sunset — subtle but all-pervasive, like a piece of music.

Water is, unsurprisingly, the theme. The stairs — red stone with white veins — are lined with mineral water bottles, seemingly left by accident. Museum staff replenish the small puddles; the tiny Jäegermeister flasks are easily missed.

At the top of the staircase, a glass display case is attached to the banister — horizontally and precariously: Wassermusik II (2025). It holds black-and-white photographs Gaillard discovered at the Musée de l’Orangerie, home of Claude Monet’s Water Lilies (Nymphéas) (1914–26), a proto-immersive environment.

As we tour the exhibition, a guard complains to the curator that visitors keep stealing the small liquor bottles scattered on the floor. I am reminded of Gaillard’s first major institutional show at KW Institute for Contemporary Arts in Berlin, The Recovery of Discovery (2011) — a great disappearing act of a sculpture. A year after winning the Prix Marcel Duchamp, Gaillard stacked beer crates into a four-meter pyramid visitors could rip open and drink from, a commentary on the decay of monuments. His early 16mm films of housing blocks and pyramid-like hotels made him a connoisseur of modern ruins.

At the top of the stairs, a vast dark room smells like an archive — dust and mothballs.The objects of the installation Wassermusik III (2025) are difficult to discern. An oblong felt strip on the floor is a carpet from the institution’s basement, on which cracks in tiles have left imprints, like a photogram. Absorbent Figure (2025), a large aluminum replica of a souvenir Buddha from Indonesia, crouches on it in deep melancholy. Exit signs, a depot shelf with pieces of furniture, are tucked away in the shadows. Two heavy Chesterfield couches, taken from the nightclub P1 beneath the institution, could be mistaken for Nazi-era paraphernalia in their unappealing clunkiness. Sadly suspended from an oak-and-iron coat rack — another 1930s archival find — is one of Oskar Schlemmer’s colorful wooden puppets, like a last violent hurrah of Nazi design against the Bauhaus.

Gaillard is interested in what could be called deep time, but simultaneously, his work seems oddly ahistorical. He is formally precise; his pieces are seductive, and their means restrained. But when you zoom out of history far enough, everything becomes vague, and sometimes it seems as if Gaillard is obsessively compiling from this heap of broken images in an attempt to resist that elusiveness.

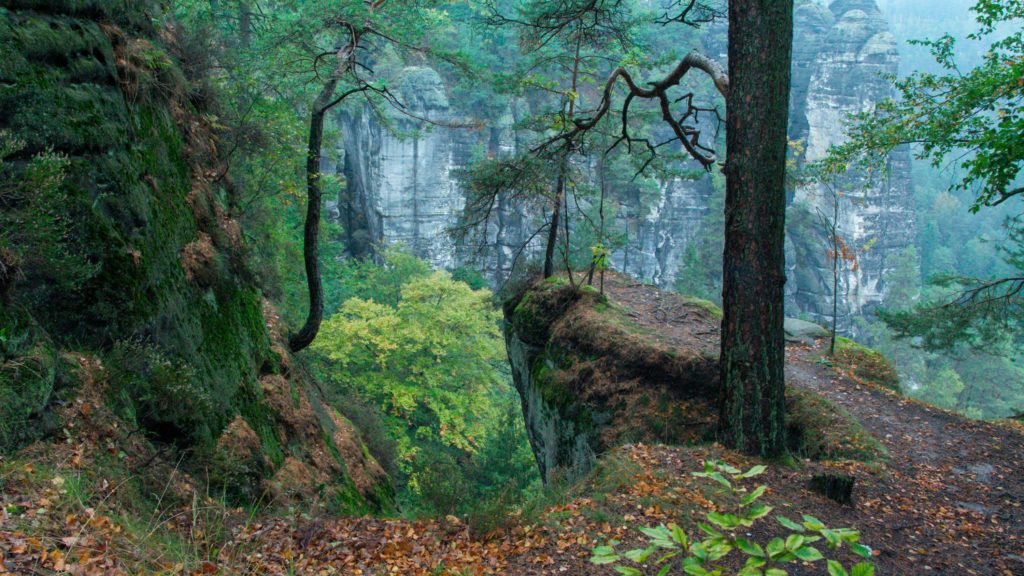

The set-up could be meditative, but the silence is pierced by the booming soundtrack of Retinal Rivalry (2024), the stereoscopic half-hour film playing in the adjacent room. At times, the film adopts a non-human perspective: the camera scurries close to the ground in Nuremberg like a small mammal, where a Burger King now occupies a power substation originally designed by Albert Speer for the Nazi Party convention. At other times, the camera soars over rainy rocks, rivaling Romantic landscape painting. The screen appears punctured by the pointing fingers and noses of statues in postwar pedestrian zones of German towns. Youth in traditional costume languish on a Munich meadow, possibly after a night of debauchery. At one point, Klaus Kinski’s voice-over from Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972) — a Werner Herzog film about a Spanish conquistador losing his mind in the jungle — is heard. Gaillard’s film betrays an oblique fascination with Germany and Romanticism; perhaps Herzog and Gaillard share that inclination. Kinski’s voice, announcing the conquest of a promised land — the jungle — is chilling.

By the time you leave Haus der Kunst, it’s almost impossible to tell where Gaillard ends and the building begins. Visual similarities do much of work here, as they did in Ocean II Ocean (2019), which hinged on the motif of the spiral, not unlike the ammonites. Like a never-ending spiral, the fragments never coalesce into a coherent narrative — but for Gaillard, it has always been about the semiotic gap between them anyway.