On Monday, October 13, 2025, just a few days after I visited Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme’s multimedia installation Prisoners of Love: Until the Sun of Freedom (2025) at Nottingham Contemporary, two thousand people — many from Gaza and held without charge — were released from Israeli jails as part of a new ceasefire agreement. The mass imprisonment of Palestinian people is cited as one of many violent tools used in Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territories, and it’s estimated that up to 40% of Palestinian men have been arrested by Israeli authorities at some point in their lives. Those released were a small fraction of the estimated 11,056 Palestinians held in Israeli prisons. Concurrent with the release of imprisoned people on October 13, 150 deceased people were returned to Palestine from Sde Teiman prison camp, many showing clear signs of torture and murder.

For nearly twenty years, Abbas and Abou-Rahme’s practice has been concerned with strategies for resisting, witnessing, and remembering experiences of occupation, oppression, and forced migration. They continue to gather a collection of texts, images, and videos — both found and self-authored — that enter and reenter their work through processes of layering and mixing. Split across two of Nottingham Contemporary’s cavernous galleries, their most recent work draws on this ever-shifting archive to grapple with conditions of imprisonment, where the ability to witness, or see much at all, has been literally obscured by occupation.

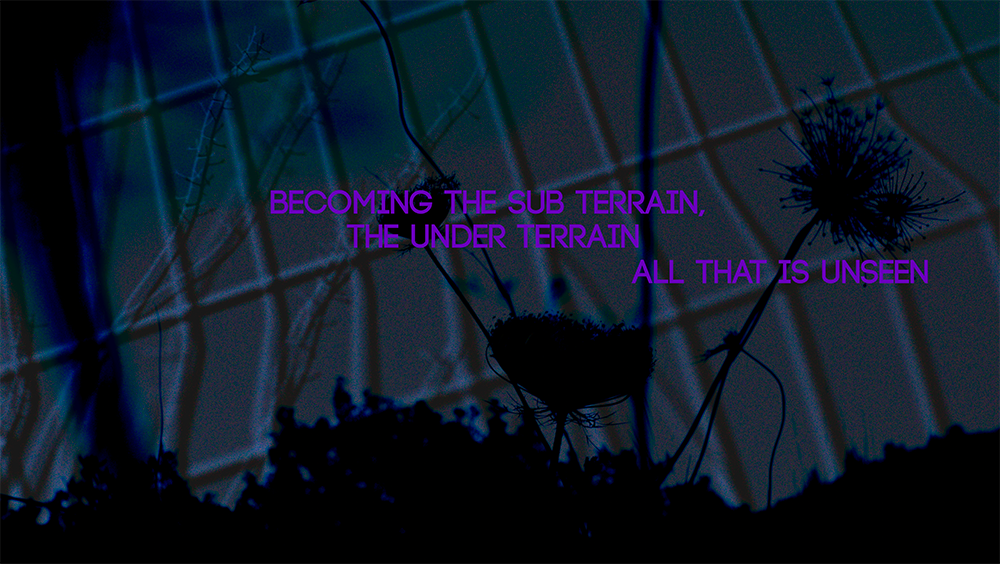

A projection dances in the corner of the first gallery: a purple thistle, a symbol of Palestinian resilience for its ability to grow in harsh mountainous terrain, hovers and jumps across the multiple planes common in Abbas and Abou-Rahme’s installations. This fragmented display adds dimension and complexity — as well as the potential to withhold parts of images through shadow — to the typically uninterrupted, flat surfaces projections demand. On the other side of the room, sheets of metal at varying heights display drawings and written fragments from the artists’ archives, including testimonials by imprisoned people. Fixed on both sides of the metal sheets, you must look closely, strain, bend, and crouch to view them.

The disorienting sound of a ceaseless rhythm, distant song, and metallic echo draws you into the second gallery, where a multichannel film installation runs on a sixty-minute loop. I sit on one of several concrete stools spaced out across the space, feeling momentarily isolated and observed. Some visitors chose to sit on the ground or to loiter at the threshold of the space. Many dip in briefly; a few stay longer. The film spans three of the gallery’s four walls, refracted across several planes. We hear more harrowing testimonies from imprisoned people, including artists, writers, and musicians, alongside footage of Palestinian people walking the land across the occupied West Bank. We also hear about the persistence and vitality of imagination in these conditions; the ability for a song about friendship to transcend the doors of a cell and connect with others held nearby; for a drawing of a boat on a jail wall to save lives. Palestinian playwright and poet Muin Bseiso’s words appear on the screen “They won’t be able to kill you as long as you travel.” These fragments of text in Arabic and English by artists, poets, and scholars from different parts of the world, who have experienced oppression and occupation, extend the frame of the film and its understanding of imprisonment and freedom. It recounts the experiences of those for whom the ability to look is impeded by concrete and fences, but also addresses those outside of Palestine who no longer know where to look or continue to look away. Imprisonment, apartheid, and genocide are here understood to be enacted on our collective body, their consequences on our imaginary still continuing to unfold.

Much has been written about how the power of images and language has shattered under the weight of genocide and Israeli state propaganda as the violent legacies of 1948 accelerate. I feel it now, as my words push up against the edges of the page, unable to fully express the realities they attempt to convey. Abou-Rahme and Abbas have worked from and with this place they call “being in the negative.” The idea appears in Prisoners of Love as both concept and form. They write: “Being in the negative is being what seems buried but continues to sprout. Being in the negative is to see the breaks as openings.” In one section, an image of a barbed wire fence appears in negative, vibrating and shifting in and out of focus. An overlaid image of a thistle, also inverted, suddenly seems able, by a trick of the image, to slip through to the other side of the fence. The flattening of both images allows a new relationship to emerge. Even when most of the information is stripped away, something persists, imagination continues to flow, creativity abounds. It is not the failures of language, images, and sound that are framed in the work but their enduring necessity and power.

1 HaMoked, October 2025.