How do objects speak when language falls short? What does it mean to cross — not just borders, but generations, materials, time? These are the quiet but persistent questions posed in Duane Linklater’s current exhibition at Camden Art Centre, where material culture, ancestral memory, and Indigenous knowledge intersect. Linklater lives and works in Nbisiing Anishinaabe Aki, or North Bay, Ontario. His practice explores the physical and theoretical structures of the museum in relation to the historical and ongoing conditions of Indigenous peoples, their objects and forms — expressed across sculpture, painting, textiles, film, and installation. Collaboration is central to his work, often involving family members and long-term interlocutors such as Tanya Lukin Linklater and Layli Long Soldier. The show is technically a solo presentation, but from the moment you enter, the idea of singular authorship starts to dissolve. There are too many threads, too many lives stitched into the fabric of the show for it to belong to just one person.

Curated by eleven fellows from the New Curators program — a year-long training for aspiring curators from lower socio-economic backgrounds — the show could easily have felt disjointed. But as director Martin Clark noted ahead of my visit, the notion of “too many cooks in the kitchen” does not apply here — the result is unexpectedly cohesive. It doesn’t suffer from overcrowding or competing voices. Instead, the exhibition feels considered, spacious, and fluid — like something gently unfolding rather than arranged. Each curator’s presence can be felt not through overt signatures, but through a shared sensitivity to Linklater’s themes of transmission, loss, and cultural continuity.

The word akâmi comes from the Omaskêko Cree language — a language spoken by people from the Moose Cree First Nation in Northern Ontario — loosely meaning “across.” That sense of movement — of traversing and layering — is present throughout. The show resists linear readings in favor of encounters: across time, across familial lines, across the categories of art, craft, and object.

In the first gallery, a series of paintings bleed with restrained force. Made using tea, syrup, and other organic pigments, they evoke more than they illustrate. The works seem to hover — between land and architecture, visibility and trace, memory and map. Their surfaces carry the weight of erased histories, yet hold something alive. You don’t look at them so much as with them.

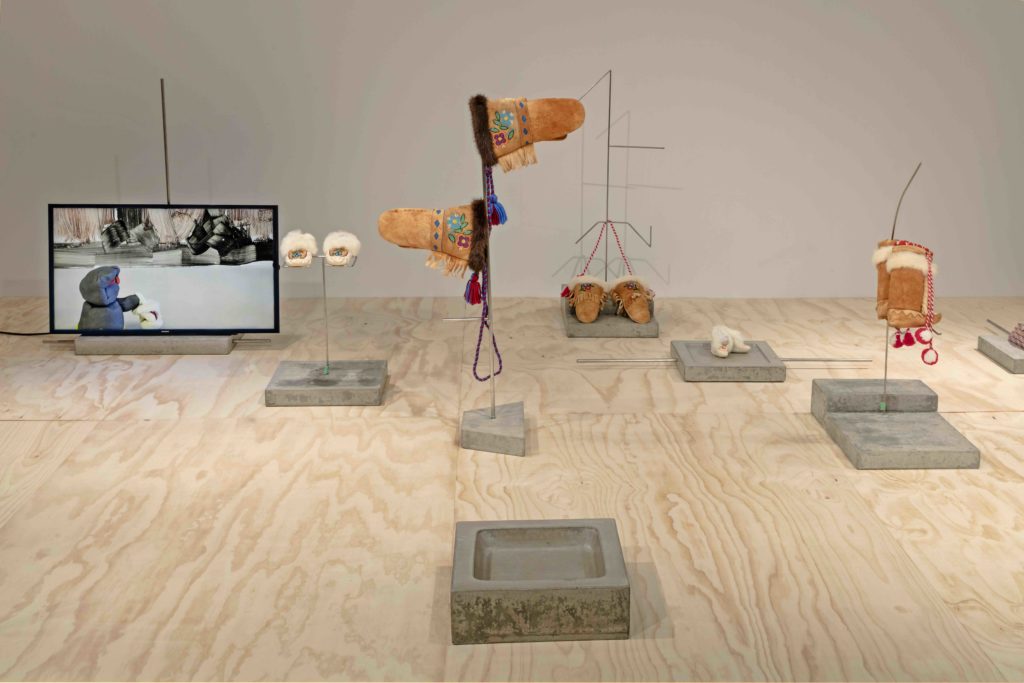

Across the space, other pieces unfold slowly — objects that aren’t quite installations, but arrangements of relation. Slippers, flowers, tobacco leaves, steel frames, a stop-motion film. Together, they form a constellation that doesn’t declare a single meaning. They feel gathered rather than authored — like the aftermath of a conversation that lingers in the air. And somewhere in that constellation is a wooden platform. On it, a bouquet of flowers, packs of Marlboro cigarettes, a handful of other personal and not-so-personal items laid out with care. They don’t explain themselves. But in their stillness, they carry something — grief, maybe, or offering, or just the need to mark a moment in time.

There’s no pretense of neutrality here. The materials are specific. The references are heavy. Yet what’s striking is how open the show remains. At one point, a low frequency seems to gather in a corner, deepening the gravity of a nearby piece. The sound doesn’t guide so much as attune — heightening your awareness of things unsaid. Even the clay vessels in the reading room — modeled after a pot removed from coastal Alaska decades ago — refuse to be pinned to authenticity or origin. Instead, they act as propositions: What if the past isn’t something we inherit, but something we recompose, again and again?

A soundscape threads through the galleries — at times felt more than heard. It’s barely perceptible, a murmur that seems to emanate from the walls themselves. The sound doesn’t demand attention; instead, it lingers in the periphery, creating an atmosphere that is more sensed than listened to. It echoes Linklater’s interest in forms of knowledge that resist the dominant structures of display — the museum, the archive, the authored object. It’s ambient, almost dissolving, like a trace of something unspoken. And perhaps that’s what this exhibition is really about: the insistence that there are other ways of knowing, other ways of making, that don’t rely on clarity, hierarchy, or individual mastery. Rather than offer a singular perspective, the show becomes a kind of shared field, where people, materials, memories, and questions circulate. It’s not seamless. Nor is it trying to be. That’s precisely what makes it feel alive.

I step outside and light a cigarette, only then noticing they’re Marlboros. Of course they are. I laugh a little. Maybe I’m part of the installation now. Maybe we all are.