In October 2023, Ruofan Chen spent a cold October north of the arctic circle at a residency in Fleinvær, a remote Norwegian archipelago. Overlooking the Norwegian Sea, the three-square-meter wooden house was highly exposed; cables cinched it to the ground to prevent toppling, and the rising tide had already breached two houses closer to the shoreline. In Fleinvær, climate change has ceased to be an ideological threat and become a stubbornly material reality. In the face of the increasingly erratic weather that had driven many former residents off the archipelago, Chen’s residence “became like another layer of clothing,” a second skin, at once protecting her from the harsh weather of the arctic circle and mediating the climate, tempering its wind, dust, noise, and temperature. In a sentiment addressed directly to the house as a friend and collaborator, Chen wrote: “October 16th, 15:00, gale force winds still blow. Many thanks to this wood house, secured tightly by the wire rope. It’s really good to have you these days.”

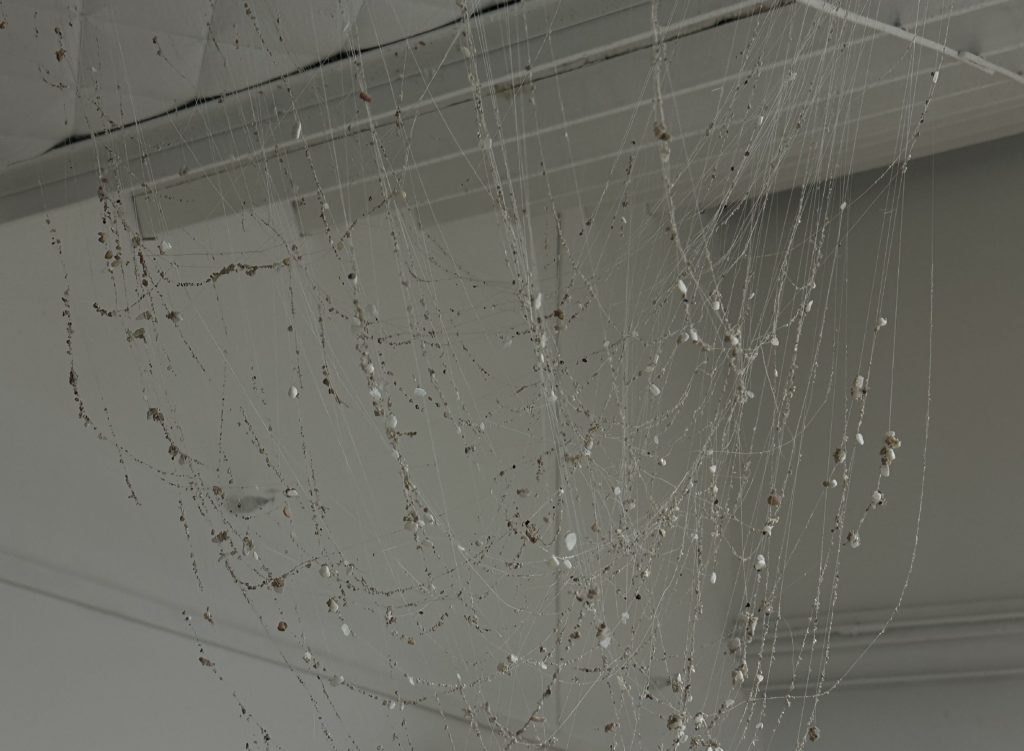

Out of this intimate relationship with her lodging came the work Soft Window (2024), a partial recreation of the windowed wall of the house, made out of an oak frame and elastic fabric, materials meant to conflate the closeness of shelter with the intimacy of skin. The cut wall is toppled and askew, almost flat against the floor. Chen writes, “collapsed below the horizon,” as if it were a piece of debris in the wake of a speculative obliteration by frenzied arctic winds.[1]Floating above the window is a hanging mesh of wire into which Chen affixed granules of sand, stone, and sawdust. In her statement about the piece, Chen notes a relationship between the intransigent problematic of climate change that she encountered during her during her stay in Norway and what she calls the “slow intrusion” of dust — particles in the air whose presence becomes known only when they accumulate into disruption: a cough, friction heat, or the darkening of a smoggy sky.[2]

In Chen’s work, incremental effects lead to chronic harms that become aggregate, obstinately material threats. These effects often appear out of “thin air” — as in the atmospheric pooling of carbon dioxide or dust inhaled in cramped workshops and factories — and produce effects in advance of moments of breakdown or illness: rising tides flooding once-habitable buildings or the rasping cough produced by dust-scarred lungs.Chen draws on personal experience as the origin of this interest. When she was three years old, her grandmother suffered a stroke whose symptoms developed gradually, in the small slippages of words or subtle distortions of speech which, at first, could be dismissed until eventually thickening into a vital threat. Attending her grandmother’s recovery, the experience left Chen’s family hyper-attuned to incremental bodily change; they cultivated a sensitivity to early signs and symptoms that might have otherwise gone unnoticed. Chen carries this symptomatic acuity into her practice, which constantly returns to the body as the ultimate site of harmful accumulation; the house is a protective layer of skin mediating one’s environment, and the air the lungs of the body of the earth.

This is not a purely metaphoric relation. As our environment grows dense with pollutants, so does the air we breathe, and, as the anthropologist Jerry C. Zee notes, the air is air we breathe together. Smog from smokestacks, desert sands whipped up by disturbed weather systems, and ash and smoke from distant wildfires all have real effects, decreasing life expectancy, instigating illnesses, and densifying air.[3] Zee writes, “This kind of breathing, measured in lost life-years, makes life and death loose synonyms; the vital functions that sustain life appear as inseparable from their own undoing.”[4] Chen’s work forefronts this materiality, revealing that the climate and the body share the same fragile air — breathing itself is a collective, and unequal, act.

It was during the production of Soft Window that Chen’s work broke away from a focus on universal environmentalism and toward the environments of labor and the effects of harmful accumulation on specific bodies working within them. During a residency in Wuhan, Chen ventured to the opposite side of the city — a trip that was marked by a noticeable decrease in air quality — in search of a furniture factory to help fabricate Soft Window. On her visit she found an airless factory floor, thick with debris amid temperatures of up to 38°C, the dim light caught on sawdust that hung in the stale, overclose air. After only ten minutes in the factory, Chen’s smartwatch notified her of the health risks of remaining in the heat much longer — in an almost immediate bodily reaction to the environment, her heart rate had spiked. None of the workers wore masks; the high heat forced them into a double-bind between comfort and protection. When Chen worriedly inquired of a coughing worker about the harsh conditions, her concerns were dismissed — they had become accustomed to it, and their precarious status as “rural-to-urban” migrant workers excluded them from access to proper health care until sickness disrupted their work.[5]

The history of labor cannot be told without an interlocking history of illness. Pneumoconiosis, an illness caused by the scarring of the lungs, is brought about by the inhaling of particulate matter floating in the thin substrate of breathable air. “Particulates of asphalt and cobblestone, motes of glass and arsenic, filings of iron, burnishings of copper” were unknowingly inhaled — or simply ignored — by workers in enclosed mines, stone quarries, ceramic workshops, textiles mills, and woodshops; at the same time, they spilled out of chimneys and exhaust pipes into the repertoire of breathable air once considered endless and permanent.[6] Described as “the most ancient industrial disease,” traces of pneumoconiosis have been found in Egyptian mummies and prehistoric remains[7]In the first century, Pliny the Elder wrote that workers polishing cinnabar wore bladder-skins over their mouths to “prevent their inhaling the dust in breathing, which is very pernicious.”[8] Almost 2000 years later, in Capital, Karl Marx connected pneumoconiosis to free market economics, writing sardonically that “consumption and other lung diseases among the workpeople are necessary conditions to the existence of capital.” [9]

At Shower, a gallery in Seoul affiliated with the exhibition design studio Shampoo, Chen presented the show “Dust” (2025), shaped by her experience in Wuhan’s furniture factories.[10] In the show, dust serves as both a metonymic aesthetic form of the logic of harmful accumulation that marks this (continuing) history of labor, and a material testament of the labor that went into the production of the show itself. In a work called Heavy Dust (2025), a canted plywood wall cleaves the space, slicing it like a wound. Similar to Soft Window, the toppled wall gives the impression of unmoored debris, teetering into the darkened space of its backside. Inset among the sheets of plywood that make up the wall’s surface are delicate oil paintings on elastic fabric, of grids disappearing behind a horizon line, resembling the neutral and unpolluted space of 3D simulation software. They are composed with brushwork that evokes the sandy texture of sawdust and are pricked with sewn silk threads that hang in the space behind the wall. The obverse side is dark, and sawdust left over from the wall’s production is swept around slanted rectangles of light produced by gallery light streaming through the transparency of the fabric. In the exhibition’s insistence on an equivalence between the object and its production, “Dust” highlights the relationship between art and labor; the blind reification of art objects is denied in favor of a logic that highlights labor as an integral aspect of the work itself — and the pernicious effects of ignoring that relation.

Exhibited on the reverse side of Heavy Dust, Protection Cover (2025) continues Chen’s interest in shelter that began with Soft Window, although this time the outside is sheltered from the harsh environment of an interior. A computer simulation of swirling dust, a replication of Chen’s experience of the furniture factory, is projected onto a hanging sheet of silk fabric. Nearby, the recorded sounds of an active construction site can be heard through a closed door; saws whirl and slice as hammers incessantly tap an off-kilter rhythm, echoes of dropped objects and the high-pitch timbre of ringing steel resounds as knotted wood is chewed through and reconstituted. Protection Cover is based on the polyethylene sheeting used to cover unfinished skyscrapers during urban construction. However, this plastic sheeting is not there to protect the workers as one might think. Instead, it exists to protect the outside environment from the dust, heat, noise, and mess produced by the construction inside the unfinished building — a reverse-shelter that, as Chen notes, “protects the city’s image, but not the bodies that build it.”

In a work exhibited in the bright space in front of Heavy Dust, dust appears as both a synecdoche of harmful accumulation and the desired result of labor. Imported around the world from France, “equestrian sand” is a finely graded, high-purity silica sand, engineered to not produce clouds

of airborne particles when trampled over, a consideration mainly for the cleanliness and aesthetic clarity of equestrian sports. Dust-Free Arena Sand, Equestrian Arena Sand (2025), the smallest work in “Dust,” consists of a sieve and three layers of silk organza. Equestrian sand placed at the back layer filters unevenly through the sieve and fabric, producing a layered, sandy-beige abstract image on its surface. Dust-Free Arena Sand, Equestrian Arena Sand explores a situation in which sand and dust become the object of production rather than its dross. Chen challenges us to imagine at once a dustless desert and a factory embroiled in the dusty production of its sand: a denatured form of the very detritus that has for so long been a chronic scourge of laborers toiling under the yoke of free-market exploitation.

A careful reading of the progression of Chen’s work emphasizes the importance of a symptom-oriented framework, attuned to incremental changes that threaten to spill over into total breakdown, and that sees this as a problem of the body — of illness and degeneration — expanding necessarily into our shared environment, the threatened commons of breathed air, and into the dusty crevices of life and labor. Everywhere in the world today, processes of harmful accumulation whose symptoms have long gone ignored by those with the power to change them are coming home to roost. In Chen’s work we discover a methodology for diagnosing these issues ourselves, and a hope that we might all become more like Chen’s family in the wake of her grandmother’s stroke: attuned to the slow violence that makes its effects visible in the incremental degenerations of the world, our environments, and our bodies.

[1] Ruofan Chen, “shelter,” accessed October 24, 2025, https://www.ruofanchen.com/copy-of-archive-tiny-units-close-to-e.

[2] Chen, “shelter.”

[3] Jerry C. Zee, Continent in Dust: Experiments in a Chinese Weather System (Oakland: University of California Press, 2022), 144.

[4] Zee, Continent in Dust, 144.

[5] T. Hesketh, T., X.J. Ye, L. Li, and H.M. Wang, “Health Status and Access to Health Care of Migrant Workers in China: A Comparison with Other Chinese Population Groups,” BMC Public Health 8 (2008): 93, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2239328/

[6] Hillel Schwartz, Making Noise: From Babel to the Big Bang & Beyond (New York: Zone Books, 2011), 433.

[7] A. J. Orenstein, “The History of Pneumoconiosis,” South African Medical Journal 32, no. 12 (1957): 797–802.

[8] Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 33, Section 41, trans. H. Rackham et al., Attalus: Classics and Ancient History, accessed October 24th, https://www.attalus.org/translate/pliny_hn33b.html.

[9] Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume I, trans. Ben Fowkes (London: Penguin Books, 1976), 316.

[10] The installation was fabricated and maintained by Shampoo. Chen stopped working with the factory in Wuhan after trying to connect them with proper insurance and safer technology, which was refused.