“Form – it’s because there are consequences,” writes poet Lisa Robertson.[1] I came across this line late at night during one of those instances of insomnia-fueled giddiness, perusing the pages of random books that fall open by chance, interspersed with a digital tumbling down the on-screen rabbit hole. Since that fateful nocturnal encounter, I’ve been coming back to this short, matter-of-fact statement while looking through images of work, past and present, that constitute the object-laden world of Norwegian-German artist Yngve Holen. Robertson’s meandering prose might seem galaxies away from Holen’s staccato sculptures, their clinical precision as close to a visual equivalent of Morse code as one can get. But it is in her insistence on texture, on the way that the shape of a sentence can structure and affect identity and our experience of reality, that poet and artist are closer than they may initially appear.

[1] Lisa Robertson, “7.5 Minute Talk for Eva Hesse (Sans II),” in Nilling: Prose Essays on Noise, Pornography, the Codex, Melancholy, Lucretius, Folds, Cities and Related Aporias (Book*hug Press, 2012), 45.

In the past, Holen too has made it explicitly clear that it is form that drives his practice as he picks apart the specific history and shape that any object carries with it as a marker of its existence. In the same way that language offers some semblance of understanding through linguistic analysis and translation, Holen’s sculptural practice and editorial projects are a constant questioning of the ways in which objects structure our personal being and relationship to the surrounding world, using a conceptual and formal toolbox comprised of hacking and collage, sampling and processing, systems and narrative. If we apply Robertson’s statement to Yngve Holen, what transpires is an insatiable quest to come to grips with the impact of form — whether man-made or natural — on human development and desire. Put simply, he turns objects, shapes, and images into icons reflective of our decrepit reality, a techno-driven society that has drank the Kool-Aid. Always wanting more, we’re taught that faster, bigger, harder, sleeker is always better.

Courtesy of the artist; X Museum, Beijing; Galerie Neu, Berlin; Modern Art, London; and Neue Alte Brücke, Frankfurt.

Courtesy of the artist; Galerie Neu, Berlin; Modern Art, London; and Neue Alte Brücke, Frankfurt.

SUV tire rims, washing machines, kettles, animal carcasses, Lego toys, airplanes, the porn biz, the human brain: all of these, at one point or another, have been thoroughly dissected (sometimes, in the most literal sense) by Holen. Messy insides and sleek interiors are his lingua franca. Who can, for example, forget CAKE (2016), a Porsche Panamera that the artist had sliced neatly into four equal parts and presented as a pièce de résistance at Kunsthalle Basel that same year? Sitting in the middle of the gallery, the car’s still-pristine exterior gave way to an altogether different picture on the sides that had been cut through via diamond wire with laser-precision: the metal parts, joints, wiring, and whatever other bits and bobs that effectively make up this luxury commodity and that are usually hidden from view. Suddenly on display are the guts of an immanently alien body, strata exposed like the layers of an archaeological dig.

Where does this obsession to slice things open and peer inside come from? For Ida Eritsland, writing about the artist’s work in the catalogue accompanying “Foreign Object Debris” (2021), his first monographic exhibition in Asia at X Museum in Beijing, it’s because “our selves are still mysteries to us, medicine a battlefield, our frail bodies the ultimate metaphor – as well as ultimate (physical) reality.” [2]

Holen is effectively asking out loud the same questions that we quietly mutter to ourselves, hoping no one else will notice. To do so, he takes apart corporate mindsets, industrial production, contemporary food production, and high-speed travel — all bound by manufacturing processes whose original concern is focused on innovation, effectiveness, and the commodity form and its circulation. In his works, products lose their intended specificity and function when subjected to principles of assembly and collage. Taken out of their original system of usage and turned upside down, they are scaled up or down, flattened, splayed, caught in a spin cycle. Often privileging the techniques of 3D printing and scanning, Holen undertakes a meticulous deep dive, delving into the innards of objects, turning opaque structures momentarily comprehensible, or at the very least feigning the possibility of understanding.

Take Exhaust (2021), a printed wall-to-wall carpet of a cow carcass, the image taken from a slaughterhouse in Hamburg and blown up to fit the proportions and surface area of the museum floor. Wall-to-wall carpeting on steroids with a drop of acid thrown in for good measure to optimize the hallucinatory effect of tiptoeing on a visceral mess of flesh, blood, fat, bone, and fibers. There is something obliquely baroque in seeing this gory flatpack image stretched out into infinity. It also visually and affectively echoes an early scene in Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s tragi-romantic film soliloquy In a Year of 13 Moons (1978), in which documentary-style footage presents the exsanguination, skinning, and evisceration of cattle, blood pooling all over the abattoir’s floor, as a graphic visual backdrop to the melancholic reverie of Elvira, the film’s protagonist. As we follow her recollections and trace the last days of her life before it culminates in the grand finale — her suicide — she recounts the story of her adult life and her experience of working in a slaughterhouse while still living as a man.

In the same way that the pairing of skinned carcasses hanging on meat hooks reflects but also creates a distancing effect with Elvira’s interior excavation, the sacrifices she has made in a failed attempt to find love, happiness, and acceptance, and, ultimately, her conviction in her impending obsolescence she is both the butcher and butchered — so too does Exhaust, through its obliteration of an acceptable notion of scale, challenge and blow up the consumer’s one-person perspective. In Holen’s hands, this particular image — rather than representing the silent victims of a global agricultural industry gone berserk, producing fodder to be consumed by a rapidly growing population of late capitalism’s servile handmaidens — consumes us instead. In so doing, it highlights the overlapping realm between man and machine, in which dislocation becomes key. It also offers a partial explanation of why food — in multiple guises and states of being — is such a constant presence in Holen’s practice.

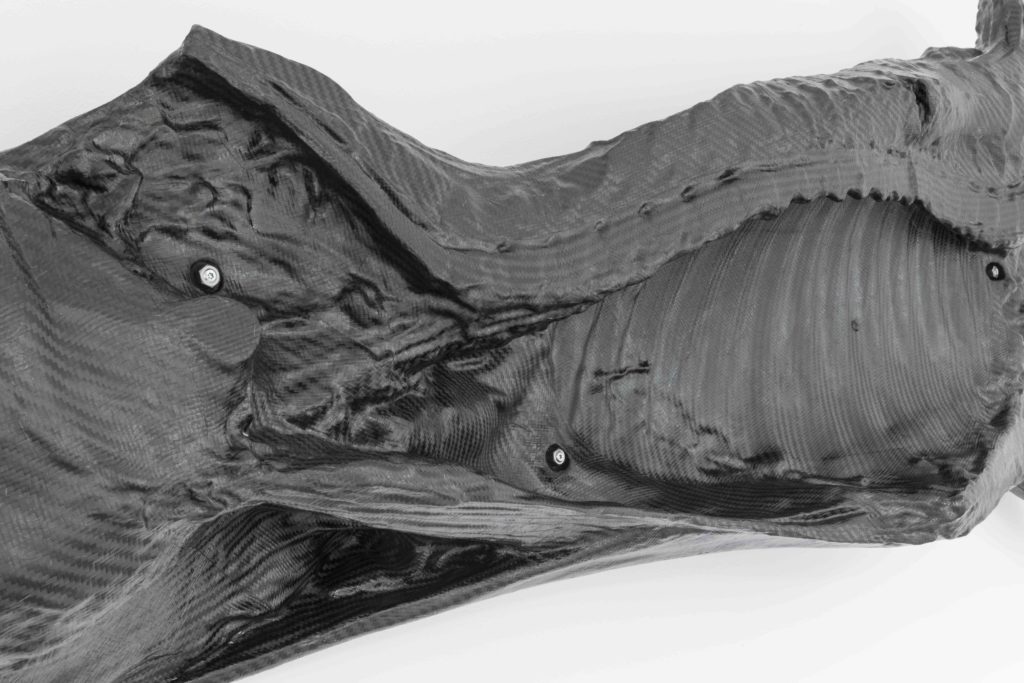

A titular work in “Foreign Object Debris” was FOD (2021), an abbreviation, half a cow carcass made from heat-resilient foam, wrapped in a gleaming, black, carbon- fiber skin, and mounted directly on the wall in the likeness of a hunter’s trophy kill. If Exhaust relies on the principles of anamorphism to render impossible the reading of the image in its entirety, FOD uses the tried-and-tested method of opacity, the presence of the sculpture’s invisible, internal material suggested only through the work’s written description, the hard carbon-fiber shell obfuscating what may actually be a void lying behind it. In the artist’s own words, “I wanted to make an organic form using this very bro racing aesthetic. I wanted to mix the car industry with the meat industry.”[3]

FOD, like the exhibition title, comes from the world of aviation. It’s an insider’s lingo to denote things that have been forgotten in a place where they don’t belong, and that can lead to fatal consequences. According to the FOD Control Corporation’s website, examples of such debris can include anything from paper clips, volcanic ash, birds, fragments of broken pavement, to loose bits of hardware, baggage tags, or even humans. Literally anything taken out of its original context becomes a potential hazard. However, the term can be equally applied to the entirety of Holen’s practice, in which everyday objects, natural and artificial, are continuously rearranged and displayed in a manner not entirely in keeping with who or what they are.

Most recently, another form of farming, again intended to satisfy global consumer needs, has caught the artist’s attention. For his first solo exhibition in Mexico earlier this year, “Furrow,” Holen lined the pristine white walls of Galerie Nordenhake with agave leaves cast in brass at a 1:1 scale. Each cast was taken from a different leaf, all of them hung at regular intervals and pointed assuredly downward. Self-consciously playing on national stereotypes and clichés, Furrow (2025), as a vernacular form and image, is so ubiquitously present in Mexico that it becomes unseen. It also shares characteristics with CAKE, or with pieces like HEINZERLING (2019) and Rose Painting (2018), huge spirals of cross-laminated timber (CLT) that seem to carry a quasi-spiritual aura with their uncanny resemblance to stained-glass rose windows, but which in fact are simply enlarged copies of SUV tire rims. Faith has jumped ship and is no longer a product of nature but rather an object of design. Designer babies, designer chickens, designer everything. In earlier times, human beings erected cathedrals, temples, and other places of worship. Now we make driverless, automated cars and charge hundreds of thousands of dollars for the privilege of spending several minutes crossing the international border into space. Remember that photo of Katy Perry kneeling down to kiss the ground after having burned another hole in the ozone layer?

In Furrow, the unassuming leaves of the agave plant, valued for both their healing and inebriating qualities, feed into yet another sequence of industrial complexes: cosmetics, well-being, alcohol. On a purely formal level though, these solid bronze patinated pieces remind me of bovine horns — bringing us back full circle to meat, or at least to the idea of meat before it stops being animal. I recently learned that Holen attended a Waldorf school in Germany, which came as no surprise to me. These educational establishments are based on the approach of Rudolf Steiner (1861–1925), an Austrian occultist, social reformer, architect, and esoterist, who promoted “child-centered” teaching in order to educate the child intellectually, physically, and socially. Most tellingly, however, among Steiner’s philosophies, is the notion of the cow horn as a central tenet of the theory of biodynamic agriculture, an antenna which receives and emits vibrational energy and, therefore, acquires a symbolic value far beyond its humble shit-stained form.

Previously, as a semi-autonomous and complementary part of his practice, Holen has plunged into industries foreign to his own direct experience through ETOPS, a series of publications that read and look like inflight magazines. Here he interviews experts — all of whom remain anonymous — from the fields of brain and plastic surgery, pornography, aviation, and climate change. Offering fascinating, if occasionally macabre, glimpses into foreign worlds, these publications reveal more than anything that we’re essentially winging it. Living on a prayer. If only to prove a point, the term “ETOPS” is an acronym referring to a set of regulations and standards issued for long flights to ensure that you or I don’t end up in the middle of the Atlantic. But it’s also a pilot joke that stands for “Engines Turn Or Passengers Swim.” On January 28, 2025, the Doomsday Clock — a design that measures and estimates the likelihood of a human-made global catastrophe — moved one second closer to the precipice of no return. “It is now 89 seconds to midnight.” I guess we are all in need of some luck.

[2] Ida Eritsland “Foreign Object Debris,” Foreign Object Debris (Distanz, 2022), 178.

[3] Philip Maughan and Yngve Holen, “Scale Failure,” Kaleidoscope 40 (SS22): 110.