A transformation is happening in Joe Bradley’s work. This is nothing new; throughout his two-decade-long career, the American painter has repeatedly changed trajectory. From his early minimalist, modular pictures to the “Schmagoo” paintings (2008) — doodle-like figures on unprimed, dirty canvases — that brought him fame, all the way to more recent experiments with gestural abstraction, Bradley is constantly grappling with his medium of choice. The exhibition at Kunsthalle Krems, an hour by train from Vienna, brings into focus the latest of his stylistic changes: with a newfound tendency towards figuration, Bradley seems to have shifted into uncharted territory.

While the exhibition — Bradley’s first institutional show in Austria — is presented as a retrospective, a good part of the roughly ninety pieces gathered for the occasion originate from the last five years. As such, what emerges is less of a long-term perspective on the artist’s varied digressions than a snapshot of his most recent work. The older works frame the new chapter as something that has been a long time coming — a change brewing under the skin of Bradley’s canvases before finding an opportunity to emerge. This curatorial choice is reflected by the exhibition’s chronological route: the result is a tidy, at times rigid, narrative, presenting Bradley’s art as evolving in a largely linear fashion. The first room’s Abstract Expressionist–inspired blotches of color develop contours in the second, as figures begin to emerge and the brushwork grows more minute and refined. Bradley’s abstract forms then condense into equally bright and impactful characters –– such as Dum Dum (2025), a totemic figure with vermilion skin and zigzag legs. Still, to call his latest work fully figurative would be a stretch, as the canvases seem to constantly be on the brink of falling back into chaos. In Good Work (2025), for example, a dog’s snout and a gaping eye hover above a cluster of color fields and lines, equally chimeric and carnivalesque. It’s a playful, eerie mess.

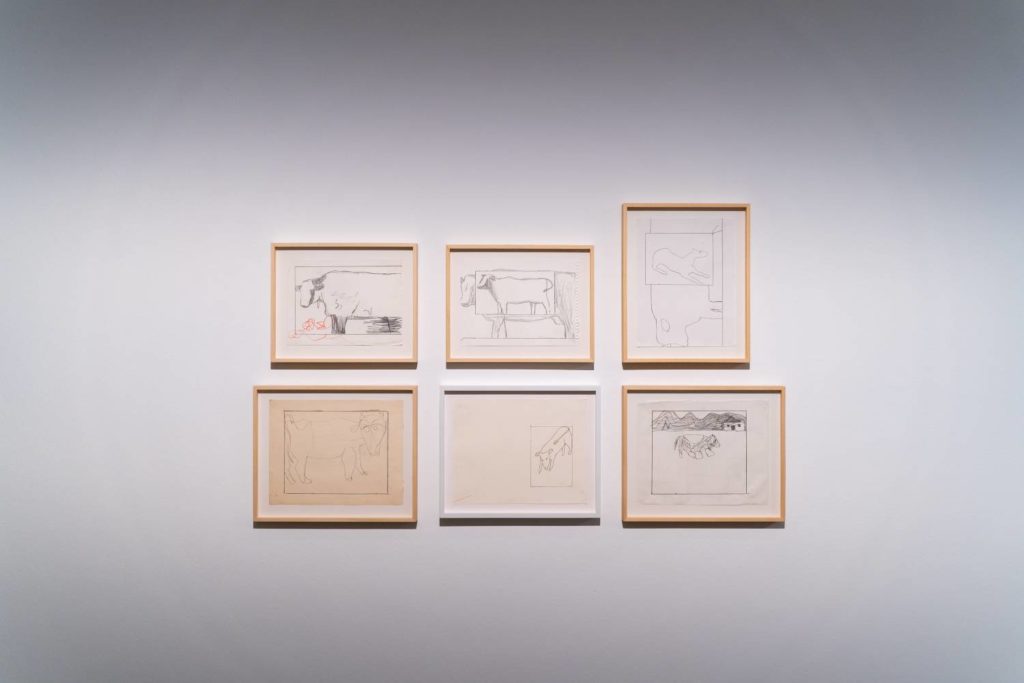

The friskily unrestrained character of Bradley’s new canvases can be partially traced back to his long-running passion for the world of comics and cartoons. This becomes evident when looking at his drawings, which alternate between childlike doodles and more tentatively refined sketches. While Bradley’s references range go from pop culture to art history, his works on paper share the speed and roughness of quick thinking. As he noted in a recent interview for émergent magazine, his drawings are always ahead of his paintings, leaving the latter to chase the spontaneity of the former. This search for immediacy, if not for vulnerability, is at the core of Bradley’s latest family of works. At the same time, his new canvases show a carefulness and attention to detail that was missing from his earlier production. The aloofness and irony of his artistic beginnings seem to have shifted toward a more expressive, straightforward approach to painting. In the aforementioned interview, Bradley admits that he’s now “happy to cop to that, to authorship or whatever.”

Less conceptual, more spontaneous, then: the Krems retrospective celebrates this change in a coherent way, offering a picture that feels linear and clean. But while the tidiness of this narrative is reassuring, I can’t help but wonder whether a less harmonious route — one that allowed the many folds of Bradley’s career to gather and clash — might have produced a more compelling portrait of his truly heterogeneous path. What has changed, what has been lost? I find a partial answer in the last room, which brings together some examples of his modular paintings. These are monumental, almost cold in their ordered minimalism. Discovering them at the end of the route lends their rigor and impersonality an even more striking force. The contrast brings them to life, giving them a brisk sort of beauty.