Have you ever walked through a park or a forest and noticed a faint track veering off the official path, pressed into the grass by repeated footsteps, a route that feels immediately right, as if the body found it before the mind could explain why? A desire path is a spontaneous and unconscious shortcut. It is an intuitive logic that is revealed only through being pursued, often — sometimes even fatally — not in advance. For many artists, it’s difficult to say how big a role intuition plays; but for Agata Ingarden, it is the structure of a mythology that continues to unfold with each exhibition.

When I entered Kunsthalle Appenzell, I intuitively walked up to the second floor. Only later did I realize that each floor of Ingarden’s show, “Desire Path,” has a name. The bottom floor is “The World.” The second floor is “The Home,” and the top floor is a smaller attic-styled room called “The Self.” Each fits within the other. And yet Ingarden’s work is a critique of how the act of distinguishing between an interiority and an exteriority is a thoroughly contingent process. The scaling of each floor is a foil that stages a further episode in an unfolding mythology.

I arrived first at the second level, entering through a glass door on which “Home”is written. “The Home” gathers hanging light sculptures from the series Hours of Dog (2020–25). Oyster shells collect into clouded bodies, lit from within so that small openings appear like windows or miniature architectures. The light is seductive but not reassuring. It creates a twilight condition where inside and outside are never fully separated. The title itself suggests a threshold hour: a time when the familiar can slip into the strange. The strange can also be read as “The World”; the shell elements appear again as a womb-like component of the sculpture Mushroom after the Rain (2019).

Nearby, videos from the “Home” floor (2018) play across six screens lined along a wall, showing footage of — or shot from — the rental vacation house where Ingarden has spent summers since childhood. Ingarden calls this “the body with organs,” in a curious appropriation of Deleuze & Guattari’s body without organs. For Deleuze & Guattari, the organism (the organization of organs) refers to the structures that guide and constrain the expectations we have of life, and the limitations we impose on ourselves. This is symptomatic of a drive that guides Ingarden’s work — namely, to perform an adaptation to formalism as a strategy of creative deviation.

Each of the screens on this floor represents an organ and a sense of both the house and the viewer of the house. The house becomes an organism, constructed through signs, objects, and personal stories. The exhibition text positions home as a site of belonging, but it also describes it as permeable, a membrane between psyche and outside systems. That image quietly undermines the promise of safety. A membrane is not a wall. The viewer pieces together the shape and feel of home through the severed limbs that Ingarden lays before us, in a curious blurring of the house as body, as self, as a filmed landscape — a blurring that once again betrays the exhibition’s formal arrangement. But that deviation is made sensible precisely through an initial adherence to the formalism of the exhibition’s space and order. We experience this home as a whole through its absence; it is a whole that coheres through evidencing lack.

In an interview accompanying the exhibition text, with the show’s curator and Kunsthalle Appenzell director Stefanie Gschwend, Ingarden describes home not as a fixed place but as a set of relations, fragile and temporary shelters built from stories, routines, objects, and dependencies. That formulation is generous, but it also opens an anxious reading: if “home” is relational, then it is also a site of power, obligation, and repetitive labor. Indeed, belonging can hold you — and withhold you. The home becomes the zone where anxiety is not resolved but simply domesticated.

The Self – 3

On the top floor, named “The Self,” two works, Social Security (Grandma’s Cupboard) and Social Security (Bathroom Fridge) (both 2022), hint at domestic furniture being converted into a monitoring apparatus. Staged cameras, monitors, reflections, and programmed live feeds produce a room that functions as a control center. It is banal, almost plausible, and that is precisely what makes it disturbing.

The viewer is invited into the loop of watching, scanning, checking, and self-admiration from unexpected angles. The self becomes an object that is managed, documented, and secured. Reflection is literal, but it is also behavioral: a training in self-monitoring that feels like a routine of self-care.

Ingarden describes Grandma’s Cupboard as a container of “stories, dreams of the past, affection and trauma,” hidden among “some sweets as well.” The camera breaches that hidden space, a gesture both intimate and intrusive. With such works, Ingarden demonstrates her perceptiveness, an ability to capture and describe the uncomfortable overlap where protection and violation look similar. Security and protection are never innocent. They take something in order to give something back.

The material motif of sugar clarifies this. In Ingarden’s thinking, sugar is not just a substance but a social condition, tied to processed food, economic constraint, and bodily regulation.

The World – 1

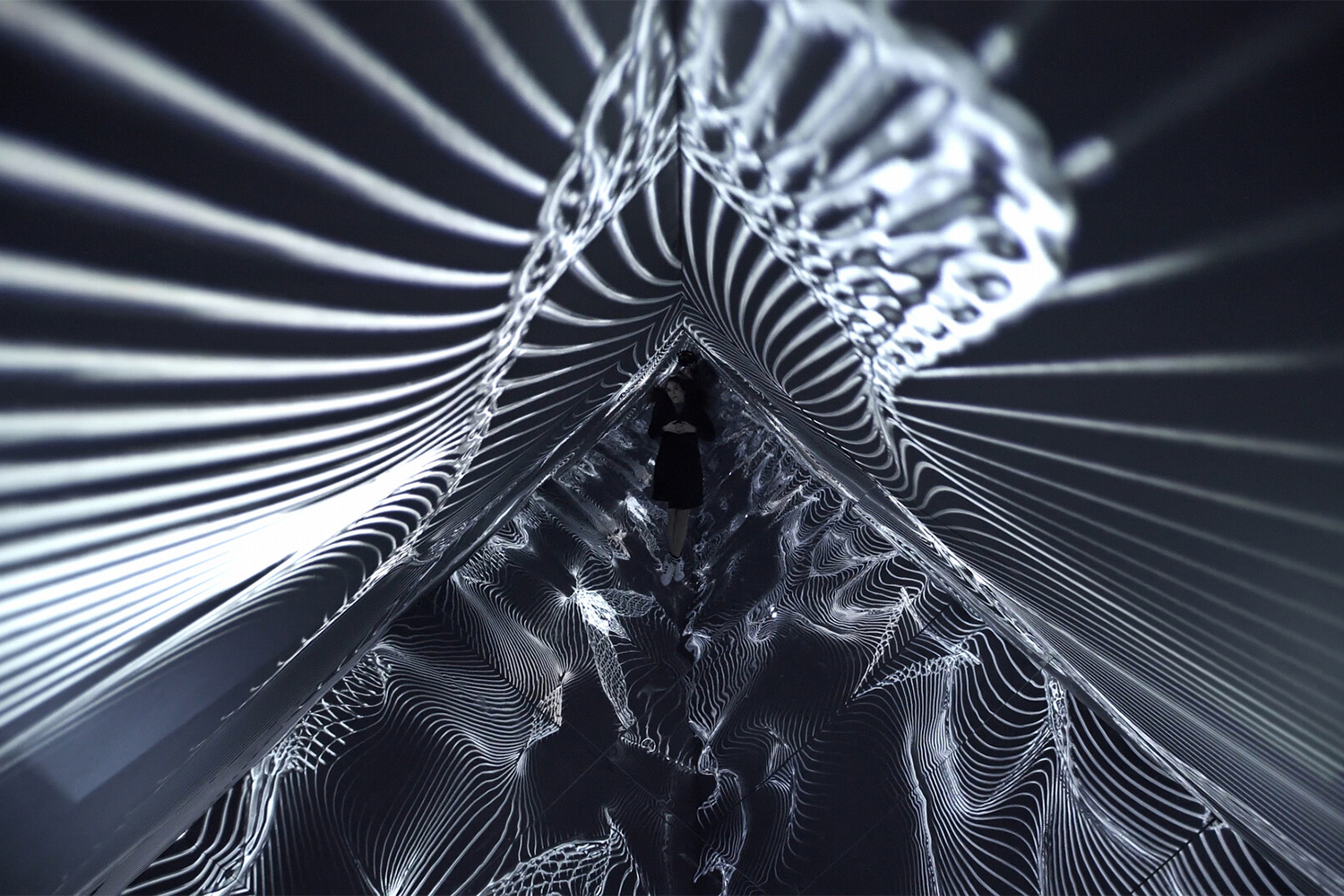

On the ground floor, Ingarden’s “The World” is not a stable setting but an ongoing process. The central work, Like Mushrooms after Rain (2019), builds a landscape out of materials that signal transformation and residue: acoustic foam crystallized in salt, carbonized sugar, oyster shells, salt, steel, and raw-cut double-sided mirrors. The mushroom’s rhizomatic networks are famously a model for networked life, a suspension of the entropic logic of an inevitable course of things. Similarly, it is hard to tell whether the structure Ingarden has assembled is decaying or becoming. The mushrooms, made out of mirror glass, take the shape of hearts. I see my reflection in them — in this landscape of industrial waste, melted sugar, and oyster shells.

The setup of the ground floor, with a huge window overlooking the utopian Swiss countryside landscape, is very peaceful and serene. The landscape of this floor refers both to the interior space within which the metal mushrooms expand, as well as the tranquil Swiss landscape, epitomizing the rural space of screensavers and videos my dentist plays to help me relax while she drills the teeth from their home — my head.

Around this landscape, on the walls surrounding this landscape, are oxidized copper mirror boards that look like displaced frames, windows, or a school blackboard. They are maps that Ingarden provides for her mythological stack.

This is the landscape of the exhibition: a mythological world of butterfly people and karma police within which Ingarden’s world and works grow. There is, in other words, a profoundly ecological character to Ingarden’s work that traverses scales. Ecology in the sense not simply of nature, but as the relational condition (or logic, to be literal about the etymology of oiko logia, or logic of the home)of existence. The conformity with which “Desire Path” is arranged over three floors — following the logical, arboreal sequence of the smaller fitting within, or below, the bigger — at once betrays, and is also teased by, the rhizomatic quality of Ingarden’s mythology and work.

“The World” is presented as an environment that does not care about the viewer’s desire for clarity. The mental maps seemingly explain some decisions made for the exhibition. Full of technical notes related to the works by Ingarden across her recent exhibitions, the mind maps also contain little self-(help) messages, which can be easily missed. One clear message stuck with me. Written in small letters, with crossovers, it reads: “love is the only remedy.”

Anxiety as a Method

If relations are the logic of existence, then anxiety is the texture of those relations. “Desire Path” is not an exhibition about anxiety, but rather an exhibition that runs on it. The Self of Ingarden’s show is a space of watching oneself from the outside; such that the most interior of experiences — my experience of my self — is always mediated by technologies of surveillance, of comparison to others, and to time. Bernard Stiegler, following Edmund Husserl, spoke of life as a temporal object, like a film, that is experienced partially and in a manner that is always fleeting. That itself may be a cause for anxiety, but for some, it would be wonderful if only moments could be forgotten.

Instead, the pervasive technological condition of self as a labor of profile-creation, of maintenance, and of technologically outsourced and indiscriminate memory (when no one seems to know what each moment is being remembered, or recorded, for) is explored across scales of world, home, and self, as having fully replaced any capacity to experience self outside of technologies of surveillance (whether voluntarily, through social media, or otherwise). Desire Path is incisive because it shows how easily notions of environment, home, and self slide into regimes of control society.

What looked like an accident at the start begins to read as an intended method. The exhibition proposes a hierarchy, world holding home holding self, a set of nested rooms. A home exists within the world, and I exist within my home. But my self is both that which exists within a home, as well as the precondition for experiencing the world as a place that I can live within. Ingarden’s show unfolds over three floors, each fitting within the one below it. And yet at each level one enters a new world in the unfolding mythology that Ingarden has created: at once contained, andthat which contains.