On the occasion of Jonathan Okoronkwo’s recent solo exhibition at Emalin, London, “Ask Not What We Were Made For” (2025), curator and architect Lennart Wolff met with the artist to discuss the processes behind his paintings and sculptures. Working with and from the scrapyards of Suame Magazine, Kumasi, his practice raises questions regarding the material and social conditions of painting as a form of planetary entanglement — one that, amid relentless extraction, a “creative metastasis” as Achille Mbembe calls it, might instead build toward collective practices of repair, reuse, and reparation.

Lennart Wolff: You were trained in painting and sculpture at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) in Kumasi. When I was teaching there earlier this year, what stood out to me was how a university centered on science and technology also houses a large art department that has played a significant role in shaping the country’s art and architectural history, from post-independence modernism to the present day. Did this proximity to disciplines like engineering, architecture, and departments such as Indigenous Art and Technology influence your practice?

Jonathan Okoronkwo: Yes, collaboration was the school’s founding idea, though over time departments became isolated — even within the art department. That began to change in the early 2000s with Professor Kąrî’kạchä Seid’ou, who revived Nkrumah’s original ethos: that artists must remain connected to other fields and to society itself. As Nkrumah put it, “the gown must go to town” — you can’t be an artist who stays in the studio, disconnected from daily life. We were trained to absorb everyday life so our work would never feel isolated from it and would remain relatable beyond the academy.

LW: As I understand it, this dialogue with other disciplines is also tied to a wider challenge to a traditional Western academic canon and myths like singular authorship, genius, creation ex nihilo, or the “workless” artwork, in favor of more radical, democratic, and community-driven practices — such as the artist collective blaxTARLINES.

JO:Yes, blaxTARLINES, founded among others by Professor Kąrî’kạchä Seid’ou, is intrinsic to my practice. Even my decision to enter the scrapyard at Suame Magazine in Kumasi came from the confidence the collective instills. The way I approached the scrapyard and its community is rooted in how blaxTARLINES collaborates with its supporters, friends, and allies.

LW: I’m curious how your collaboration with the scrapyard community in Kumasi began. I read that you also worked there as an apprentice?

JO: It’s actually a funny story. I didn’t just appear and become an apprentice. The scrapyards of Kumasi, though not far from the KNUST campus, are guarded spaces with a certain stigma — ideas of “cleanliness” shift completely there. I entered not as an artist, but as a learner, curious about machines after their working life. Through regular visits, I became part of the daily rhythm of labor. Both human and machine labor are constantly being transformed. In the scrapyard, you see this clearly through the master–apprentice system. Apprentices give years of labor before becoming masters themselves, just as machines perform labor from the moment they leave the factory. These structures are complex, and I try to approach them with humility.

LW: This recalls what Achille Mbembe describes as a fundamental function of capitalism: the compulsion to order what it extracts and, in turn, discards as valueless. Within these ongoing cycles of extraction, the scrapyard emerges as a threshold space — suspended between use and waste, but also opening onto the possibility of repair through transformation.

JO:Exactly, transformation is central to the scrapyard. Mechanics combine parts from different vehicles to build functioning machines and new tools — cookers, plastic shredders, welding devices, even staircases and bridges made from engine parts. That inventive logic shapes my practice. I extend the life of materials through chemical processes, pushing them into new states and uses. Machines are always in flux, entering new cycles of repair, reuse, or recycling when they fail. My work becomes one node in this larger material network. Here, time, decay, and use are all visible at once. A broken machine becomes a portal to new possibilities. But transformation isn’t only material — the mechanics are changed too. Their bodies adapt to oil, toxins, weight, and heat. They reshape machines, and machines reshape them. My practice sits within this loop of reciprocal change.

LW: How do the operations of de- and re-composition function within your practice as a method for generating, rather than simply arranging, visual meaning?

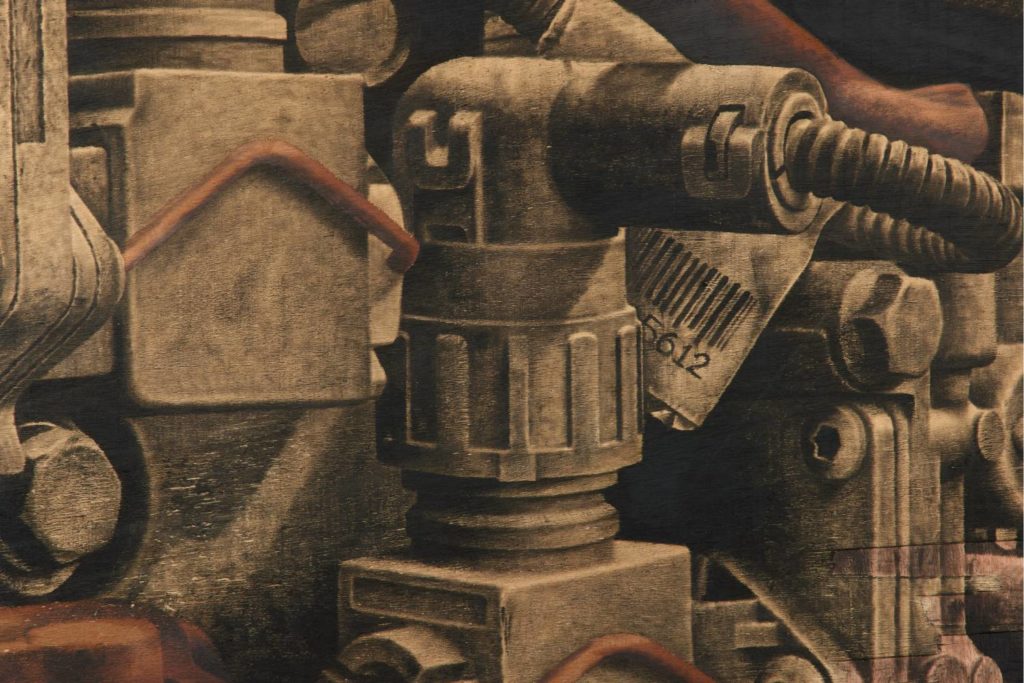

JO:I investigate machines, but also use machines to make my work — Photoshop, for instance. I collect machines through digital photographs, each capturing a different fragment of reality from different moments in the yard, which I bring into my studio where Photoshop becomes my own digital scrapyard. There, I dissect machine parts and connect them to others they would never encounter in the real world. Photoshop is where I enlarge, reduce, distort, cut, slice, and reattach. It’s where I unleash the chaotic influences of the scrapyard through my own fantastical interpretations.

Once the digital composition is complete, the next step is creating the medium. To extend the transformative logic of the scrapyard, I work with the materials extracted from the machines themselves. I use sulfuric acid from batteries to dissolve steel and iron and obtain green and yellow hues. I use nitric acid to produce oranges, browns, reds, and sometimes even pinks if I get the proportions right. Translating compositions sourced from the scrapyard with materials sourced from the same machines becomes a kind of marriage — everything coming together on the final substrate. Painting or drawing is actually the calmest part of my practice. The chaos happens before, when everything distills into what eventually appears in a gallery or back in the scrapyard.

It’s not only about machines — it’s also about the language of the scrapyard. The titles of the works come from conversations I’ve had with masters and apprentices. For instance, I’ve been inscribing some of their warnings and instructions directly into the paintings themselves, such as GBELE THE COVER TOP KAKRA KAKRA (2025), which was shown in London. I’m now translating warning signs from vehicle and machine instruction manuals into the language of Suame and other scrapyard communities like Agbogbloshie in Accra. Technology remains central. Even when it isn’t immediately visible, using a machine to dissect images of machines is something I’m very aware of.

LW: You then render these technologically mediated compositions on plywood — a highly engineered composite material historically used in various applications, including cars, airplanes, radios, ships, and construction. In Ghana, however, wood as a building material has largely been eclipsed by concrete. What, in this context, drew you to plywood as the support for your work?

JO:For me, plywood is an interesting material. I use it as the resting place for my interpretations. When you think about the origins of the substances and minerals we use to produce machines, they were once organic, before human intervention rendered them inorganic. Placing them on an organic substrate completes a loop between the organic and the inorganic. And when I study machine parts, I often observe organic shapes and forms in them — an organic logic hidden within mechanical design. Plywood also responds beautifully to the colors I make from dissolved metals and acids; it absorbs them. I also enjoy plywood’s layered structure. I can paint not only on the surface but within the layers. Some works have the first and second layers peeled away so the image sits inside the material. As an organic material deeply tied to global industrialization, plywood becomes a commentary on how transformation and industry affect the resources we extract from the earth — especially now, with rising wood prices and deforestation. It’s a kind of sweet spot for me. Most of my paintings are on it, though not all. I try to create works that are both organic and inorganic, influenced by my training as a painter and sculptor.

LW: In works such as Abossokai Macho and Co (2025), shown in London, painting expands into sculptural, spatial form, supported by the material properties of plywood, which in this configuration evoke the visual language of urban signage and commercial billboards.

JO: Exactly. Here, plywood allows me to create architectural forms as well. I’ve built paintings that are also sculptural structures — works you walk around or inside to understand. For example, the large piece from my recent show at Emalin had an imposing architectural presence. Since I install them in public, open spaces so often, I appreciate its durability. I visited the scrapyard recently to check on works I left there four years ago — some are still standing, and the medium remains visible. A material that can withstand the harsh conditions of the yard becomes symbolic of resistance: the machines resist transformation, and so do the mechanics. Even as the yard reshapes them, machines retain their material identity—steel remains steel. Likewise, a mechanic might be transformed by the yard, but he remains a father, a brother. I, too, retain my identity as an artist, even when the yard assigns me new ones. So using plywood — which resists some of the substances I apply — is meaningful. It engages in its own form of resistance. My relationship with these materials is nuanced and often too complex for me to fully understand. I’m always learning from them, always listening to what they tell me.

LW: Your account of your work process describes a cyclical passage between scrapyard, studio, and exhibition — less appropriation than circulation — which destabilizes the trope of the studio as a fixed site of authorship.

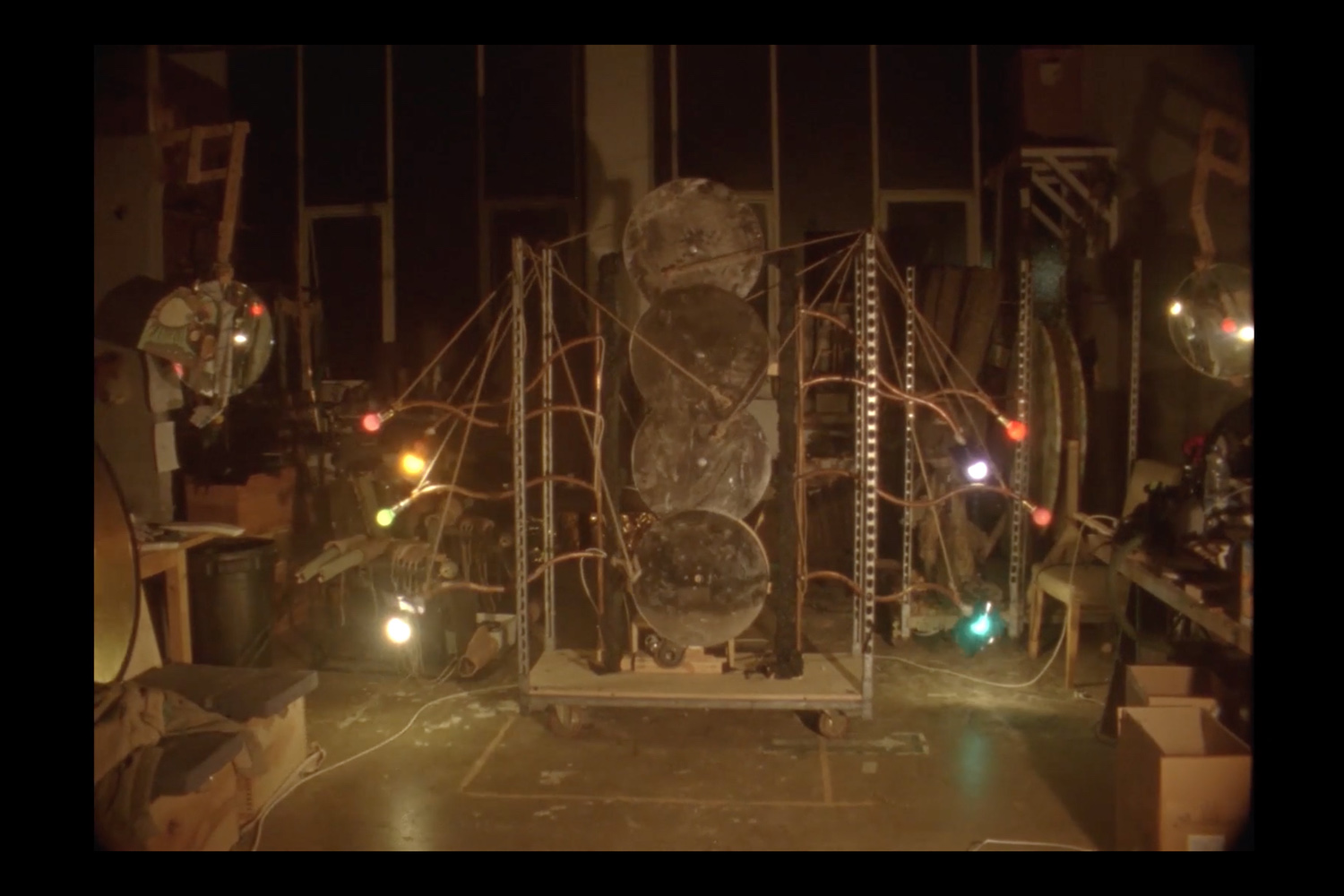

JO:There’s also a performative aspect to my work, though it’s not yet one of the most visible dimensions of the practice. I build structures in the studio, then take them to the scrapyard. I acquire scrap parts on site and weld them there over a period of time to create hybrid objects — part studio, part scrapyard. I leave these constructions in the yard and allow the scrapyard to act on them.

While doing this, I ask myself: What happens to a work of art when it’s taken out of the “sacred” space of the studio and thrown into the chaotic environment of the yard? Does it retain its aura as art, or does it become just another piece of scrap? Sometimes the works get damaged or torn apart and eventually sold again as scrap — my constructions included. This pushes the conversation further: once art enters the scrapyard, it transforms into scrap, which then becomes something intangible like money, or is absorbed into new relationships and conversations. That performative cycle is an important part of the practice.

LW: These works circulating across sites, times, and material states appear to unsettle distinctions between figuration and abstraction, foregrounding the material entanglements of capital’s systems of extraction, exchange, and accumulation. Can this be read as pointing toward broader questions about abstraction as an entangled condition of capital and technoscience?

JO:Yes, that’s true. I usually don’t explicitly talk about the systems my work emerges from — it’s always implied. Simply by being in the scrapyard, those systems are present. The scrapyard itself is born from the excesses of consumerism — the need to accommodate what’s discarded, what no longer performs the original intended function. I’m constantly aware of the capitalist structures that give rise to these materials. The substances I use are themselves excesses of machines. If that capitalist system didn’t exist, then we wouldn’t have harmful substances being produced or discarded so irresponsibly into the environment. You mentioned two things: the capitalist structures that produce these materials, and then the figuration of the image and the conceptual materialism. I’ve always considered my work to teeter between figuration and abstraction, where figuration itself takes on a nuanced meaning. How do you define what is figuration? If you say figuration, maybe it must represent something that exists in the three-dimensional world. But in my compositions, nothing necessarily looks like it exists in the 3D world. By transforming these materials, I push the work into a realm where it is constantly on the fence between figuration and abstraction. You also mentioned the materiality of the mediums — where they’re not just carrying an image or something familiar, but also bearing their own material autonomy. That’s why working with wood is interesting for me. Wood allows these materials to flourish in their own right. Some of the media react with the wood and produce interesting smells, or create textures based on how their acids react with the surface. I have to pay attention to what the material wants to say — when to increase or decrease its viscosity so that it can pass through the grains of the wood and express itself differently. Once the work is finished, the materials interact autonomously. The motor oil leaves residues and seeps into the areas treated with liquefied steel and acid. The acid softens the wood so much that I can extract layers. There’s always a dance between figuration and abstraction. The textures are not arbitrary; they emerge from the simultaneous action of extraction. A lot of my techniques are geared toward abstraction, but also give rise to semblances of figuration.