During Art Basel Miami Beach week, landing in Oslo at 0°C may not seem like the obvious choice. But step out of the airport and into the city’s waterfront museum district, and you find yourself in a cultural microcosm that feels both visionary and alive. Quietly and confidently, Oslo has built one of Europe’s most compelling ecosystems for contemporary art — compact, beautifully designed, and ambitious.

At the heart of this cluster is the private Astrup Fearnley Museet, designed by Renzo Piano and composed of two buildings joined by sweeping wooden bridges. One hosts the museum’s permanent collection; the other is devoted to Lutz Bacher’s retrospective “Burning the Days,” a survey of the artist’s provocative practice — an unsettling blend of humor, pop culture, sexuality, violence, and political unease. Across her career, Bacher probed the psychic undercurrents of the American century, often reworking symbols embedded in its national mythology.

The exhibition opens with The Road (2007), an eleven-part sequence of camera trajectories tracing the curve of a road. The shifting images pull the viewer forward with cinematic momentum. In the next gallery, In Memory of My Feelings (1990) consists of a tall metal cabinet filled with eighteen T-shirts printed with phrases from a personality test she was required to complete before surgery to remove benign tumors. The work feels at once intimate and absurd, collapsing medical bureaucracy into personal vulnerability.

Later, FIREARMS (2019), Bacher’s last completed artwork — finished one day before her unexpected death — fills Gallery 7 with fifty-eight framed pigment prints. Each depicts a gun model sourced from a repair manual, presented in precise, almost clinical profile. The effect is chilling: portraiture stripped of humanity and rendered as machinery.

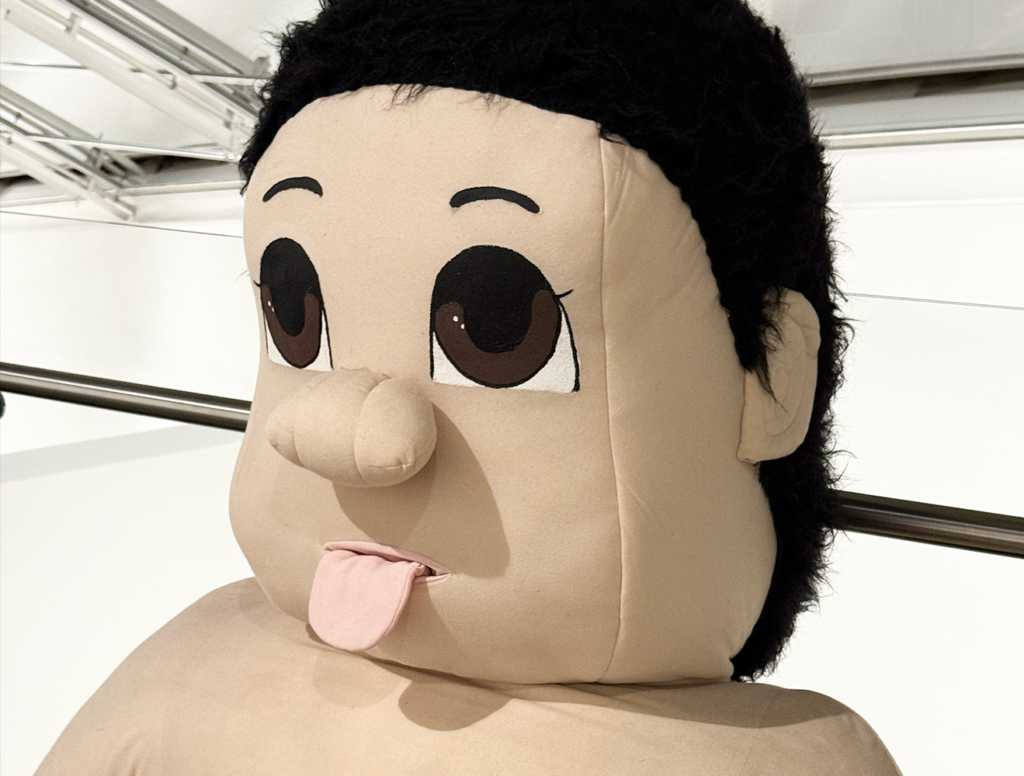

The final gallery brings together Jokes (1985–88), Playboys (1991–93), and The Little People (2005). This eclectic grouping echoes the unconventional installations Bacher staged later in life. In Jokes, she rephotographed and enlarged pages from a humor book filled with caricatured celebrities, distressing the images and leaving some outdoors to weather. The “Playboy” series (1991–94) reimagines Alberto Vargas’s well-known pin-ups through airbrushed paintings that hover between homage and critique. Together, the works capture a specific, distinctly American cultural moment while posing a lingering question:What is a joke, and who gets to define it?

A fifteen-minute walk away, the angular concrete profile of the new MUNCH Museum rises over the waterfront, hosting the second edition of the MUNCH Triennale. Designed by Estudio Herreros and opened in 2021, the museum’s thirteen floors create a vertical landscape for contemporary art, performance, and technological experimentation.

Titled “Almost Unreal” and curated by Tominga O’Donnell and Mariam Elnozahy, the 2025 Triennale explores the blurred boundary between the real and the virtual, analogue and digital, dystopian and hopeful visions of the future. Featuring works by twenty-six artists, the exhibition opens portals into parallel universes, alternative mythologies, and speculative futures. Some participants hack existing technologies—music boxes, holograms, weaving looms—while others create entirely new worlds through gaming engines and generative machine-learning tools.

Building on the previous edition, this year’s Triennale examines the evolving relationship between art and emerging technologies. Its title evokes an era in which the line between reality and unreality grows increasingly unstable. It also nods to the Unreal Engine that shapes much of today’s virtual imagery, and, playfully, to the 1993 Super Mario Bros film.

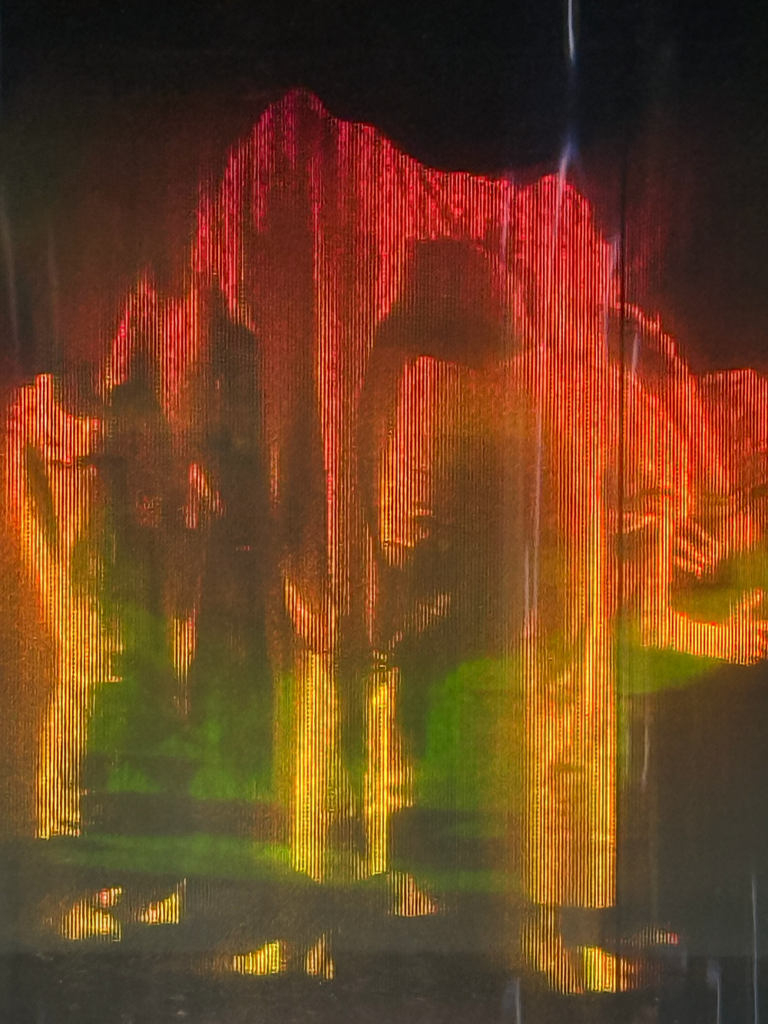

The exhibition begins with Simone Forti’s Huddle (1975), created with physicist Lloyd G. Cross. Their holographic translations of Forti’s dance works stand as radical early experiments in using technology to preserve, transform, and multiply performance — allowing choreographies to appear without live performers. Nearby, American artist Alice Bucknell presents both a preparatory film and Earth Engine (2025), a newly commissioned video game. The work challenges the fantasy that the world can be fully understood or controlled through predictive technologies. Here, the Earth’s moods and desires shape the player’s abilities, flipping the typical game hierarchy: the Earth becomes the protagonist, and the human assumes the role of an NPC. The accompanying film, Earth Engine: Ground Truthing (2025), unpacks the tools of remote sensing — GPS, climate modeling — to highlight the intelligence embedded in ecological systems.

Long before such hybrid practices were commonplace, Swedish artist Charlotte Johannesson began merging textile craft with computer technology in the mid-1970s. At a time when tapestry was dismissed as decorative or domestic, Johannesson recognized its political potential. Her woven images carry the urgency of their era: the rebellious energy of counterculture, the rise of feminism, the raw edge of punk. Works such as Terror (1970/2016) and No Future (1977) feature a stark, pixelated figure that appears across both her tapestries and early digital pieces, revealing her belief that thread and code could speak in unison — and that both could challenge the social orders of their time.

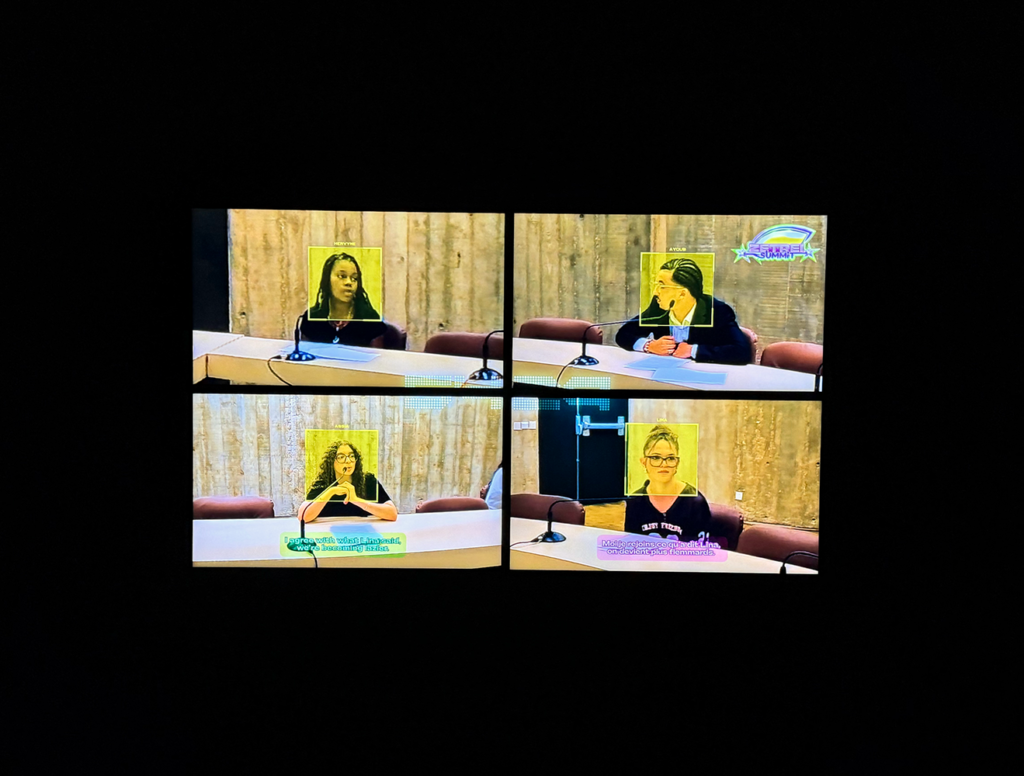

The Triennale concludes with French artist Sara Sadik’s 80 ZETREI SUMMIT (2025), a multi-channel video installation accompanied by sculptural seating. Created in collaboration with students from Lycée Alfred Nobel in Clichy-sous-Bois, the work draws strength from the imaginations of teenagers often excluded from official narratives of the future. Filmed inside Espace Niemeyer — the headquarters of the French Communist Party — the piece documents a closed-session experiment in which young participants are given one hour to envision a new world. Part performance and part social experiment, 80 ZETREI SUMMIT captures a rare moment of collective invention, as a generation debates, questions, and constructs a shared vision of the future. The installation oscillates between the playful and the political, revealing the urgent creativity that emerges when people are invited to rethink the world from scratch.

Together, the works in the MUNCH Triennale — spanning seminal experiments from the 1970s to bold new commissions — invite visitors to suspend their assumptions and imagine alternative futures.

Stepping back outside, Oslo’s cold air feels sharper, almost electric. The city may be far from Miami’s tropical heat, but I realize the trip north wasn’t a detour—it was the destination.