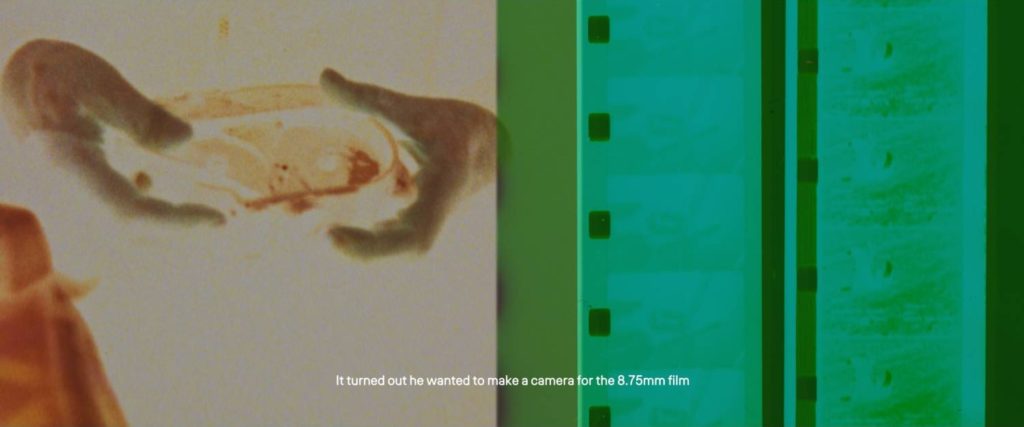

The 8.75mm is an unusual film format was conceived in France and – according to rumors – later acquired and buried by Kodak to prevent competition with its own Super 8 format. With no commercial circulation, it became particularly appealing to the Chinese government, who was looking for an easy way to bring state-sanctioned filmic entertainment and propaganda to rural areas perceived as at risk of ideological drift. Thus, between the 1960s and 1980s, factories were built near remote military sites to produce 8.75mm projectors and resize both local and foreign (yet aligned with the government’s agenda) 35mm movies. The rationale was a pragmatic interest in promoting a more portable format. Yet the government’s political interest in centralizing “cultural” production and its distribution cannot be overlooked: at the time, no other film format or camera were available there.

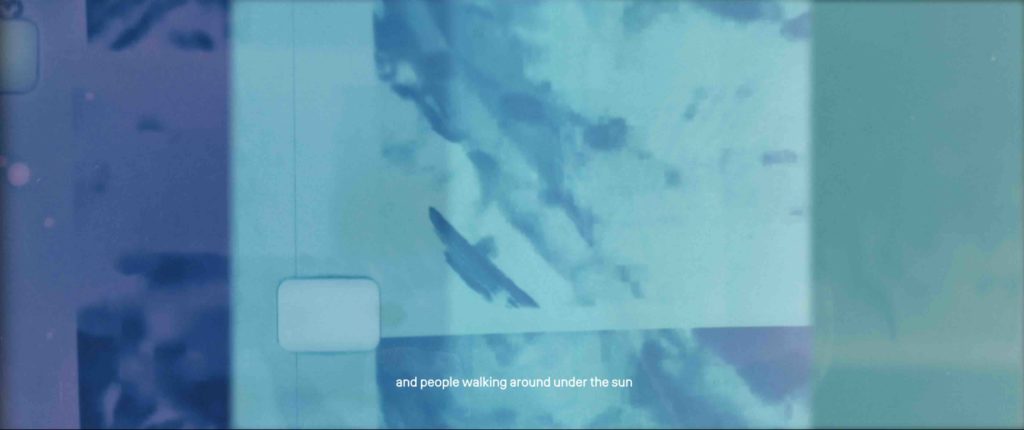

Peng Zuqiang stumbled upon the existence of 8.75mm film stock in a book footnote. From that small fragment of information, he started piecing together the events of this now-discontinued format, meanwhile engaging in a larger reflection on the fraught relationship between image-making and truth-production. For Afternoon Hearsay (2025), a three-channel work co-commissioned by The Common Guild, Glasgow, and the Rockbund Art Museum, Shanghai, Peng traveled through China to portray the places which, allegedly, were part of the history of 8.75mm, including the studio of a film projectionist and a temple once converted into a film factory, and to speak with people who, in different capacities, hold memories of the format’s existence. And yet, the film’s narrative and visual vocabulary constantly evades what would be the evidentiary scope of a faithful reconstruction. Fictional recombinations of the witnesses’ unverifiable stories are recorded in an artificially crackled voiceover, which makes them sound like they are from a distant time. Footage of the artist’s visits is superimposed with archival 8.75mm film reels bought off the internet. These are partially enlarged and photogrammed over 16mm and 35mm strips with mesmerizing results: sometimes, the smaller film stock floats in the void of the larger one like a leaf drifting in a stream; other times it sensually flickers at different speeds in series of cracks, burns, and bursts of colors.

Across his practice, Peng mixes different sources, materials, and temporalities in what looks like a purposefully unreliable archival strategy, in which opacity both mirrors the operations of stealth surveillance and offers protection from it. Installed in the same room, the filmic installation Déjà vu (2023–24) extends these resonances. The work features a projector beaming an abstract image, a black line moving in and out of focus. Peng photogrammed a wire – an ambiguous symbol of containment as much as of rescue – over an empty 16mm reel. It is sonically accompanied by a voice that flatly recount episodes of violence but which is constantly interrupted by unsettlingly heavy bass beats that excise the information being relayed, suggesting psychological as well as political suppression. What remains is indeed nothing more than a feeling of disquiet.

In a separate room, Autocorrects (2023) shows a young man wandering in nondescript places, such as airports, public transports, and chain coffee shops, over a Mandarin pop track that the artist co-wrote and recorded the lyrics. Tapping into the music video genre, phrases such as “no lies” and “somebody got in” appear laser cut into the film stock and pulled away in a fragmentary romantic narrative. A critique of institutional amnesia and covert harm but, at the same time, the “auto correct” function implies a preemptive administration of meaning and agency. As in other works, sentimentality often plays the role of a safe subject, a canopy under which a more complex reality and critique may be constructed, through which one might address unaccounted forms of biopolitical oppression and erasure.

The show, curated by Chloe Reith, brings together the last three years of the artist’s production and It compellingly highlights Peng’s spatial interest in translucency – Afternoon Hearsay is projected onto a double fabric that allows viewers to see the film also from the back, hence blurred and reversed; Déjà vu is projected onto the glass of a window; and Autocorrects is projected onto three acrylic sheets — which could allude to the porosity of images and stories when placed under material and metaphorical exposure.

The holographic effect here is key: in fact, it’s through the experience of textured abstractions, oneiric nuances, and eerie tones that the ways of living and being recollected in Peng’s films cease to be non-occurrences and become an embodied reality.