Saccharine Idyll. The words themselves promise a kind of sweetness, a softened image of comfort, the sort of scene that feels safe because it belongs to memory rather than to life. But standing among Martina Grlić’s paintings, that sweetness begins to curdle. What first appears tender and nostalgic soon reveals its fracture lines: an unease that seeps through the glossy surfaces, through the careful choreography of domestic gestures and objects. The idyll, it turns out, is never neutral. It conceals as much as it discloses; it soothes in order to unsettle.

Grlić’s practice — grounded in figurative painting and the narrative potential of images — operates like a mode of visual storytelling. Drawing on ethnographic and self-ethnographic impulses, she reimagines the everyday through a distinctly fem lens, tracing the residue of social and historical inheritance that shape both private and collective memory. I think, inevitably, of Joan Didion, whose words open the exhibition text, but also of Emily LaBarge’s Dog Days (2025), which I happened to finish reading on the way to Zagreb. Both writers, in different ways, ask how we tell stories, and why. Grlić, too, seems to be asking how an image can hold a story: how it can protect it, distort it, or let it slip away.

Her works often look as though they’ve been peeled open, their surfaces delicately torn to reveal another layer beneath. Yet that layer is always unstable, shifting — because memory itself is unstable, never still, a wax tablet continually softened and re-inscribed. Grlić paints from that flux, isolating details from photographs or objects of domestic intimacy — fragments of a visual inheritance so ordinary it become mythic. What emerges is not nostalgia but a subtle disquiet: the recognition that what we remember is never exactly what was.

“Saccharine Idyll,” the artist’s first solo show at Trotoar, Zagreb, moves like a series of recurrences, echoes that return altered. In Silk Roses (2025), silk flowers are sewn together, threaded with pearls and plastic blossoms in shades of pink and violet. The color is gentle, but the effect is claustrophobic: beauty layered to the point of suffocation, artifice mistaken for tenderness. The work feels heavy with sentiment and yet stripped of sentimentality: a meditation on how the decorative can become its own form of defense, a screen against something harder, truer.

This ambivalence continues in Dream Scenario (2025), in which a rose-tinted background evokes the soft blur of a floral motif. At its center stands the small figurines that adorn wedding cakes — icons of celebration, of union. It’s a nearly universal image, but also one that fractures under scrutiny. It is a subject that can produce conflict, even for the artist. The object that once embodied sweetness become ambiguous, resistant; the scene tips from tender to uneasy without ever quite declaring itself.

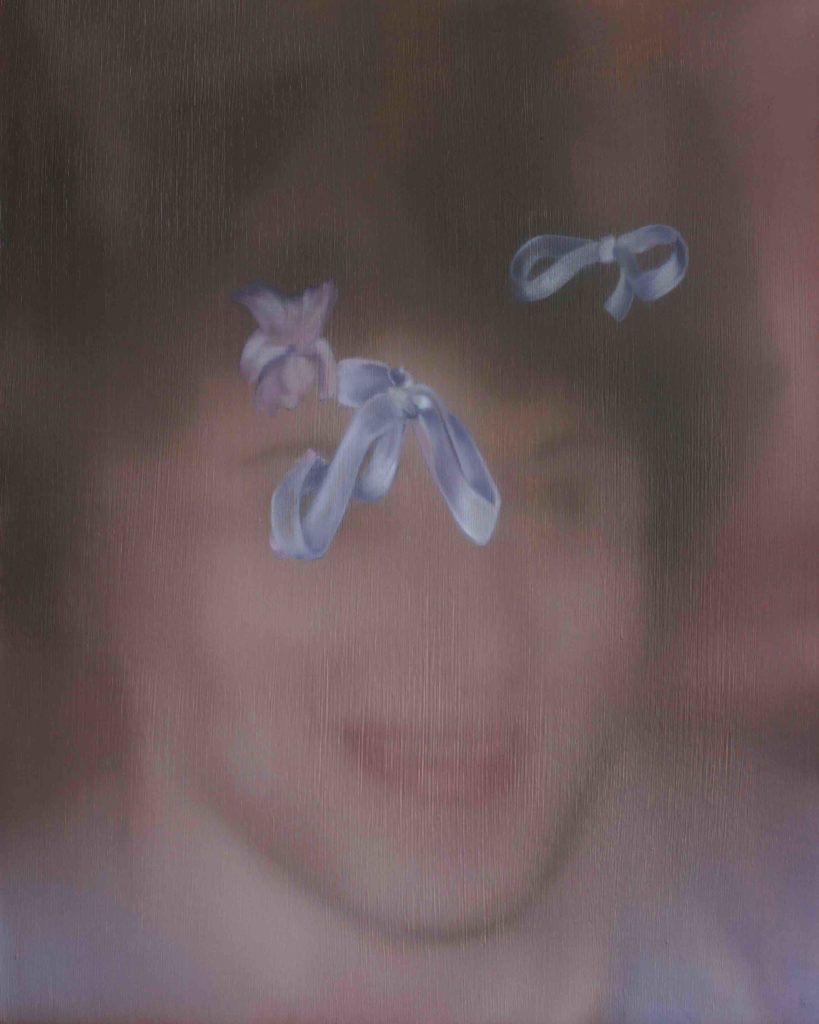

The portraits from the “Palimpsest” series (2025) offer the most intimate form of this instability. Each small panel — oil on wood rather than canvas — feels like a keepsake found and half-forgotten. Faces surface faintly against patterned grounds. Details blur, shimmer, withdraw. In Palimpsest 5, a woman with blonde hair and a violet sweater looks out from a background of yet again rose-toned motifs; above her, a cheap plastic jewel is affixed like an afterthought or an intrusion. These delicate interruptions — mostly feminine relics — act as fissures in the paint, sites where memory flickers between recognition and doubt. You think you know what you see, and then you don’t.

In Ruined (2025), a small cupid appears — the image of love reduced to ornament, or perhaps to remains. The title, with its double sense — ruin as fragment, ruin as failure — hints at the collapse that shadows affection.

Grlić has spoken about an earlier body of work devoted to the motif of cakes, fragile constructions captured in various stages of decay or destruction. “Most of my cakes were half destroyed or with candles half out,” she recalls. “Ruined is just a continuation of that, because I was almost sure I had abandoned this motif altogether — but somehow, no.” The cake paintings, like Ruined, oscillate between celebration and disappearance, between sweetness and its undoing. They hold the paradox of memory itself: the desire to preserve what is already vanishing.

The tryptic Eden (2025) feels cinematic, unfolding like a sequence caught between motion and static. In the central panel, a bird seems to hover — or is it falling? The images recall the garden as both myth and mirage, a place we keep returning to in order to reimagine our own beginning. I think of Atonement, of Keira Knightley’s character, Cecilia, running thought a field of flowers – a scene in which beauty conceals fiction, and truth exists only in retrospect. Grlić’s Eden moves in that same register: the story we tell ourselves as a way of remembering, or forgetting.

The reference to Atonement lingers not only for its visual rhyme – the movement, the light, the suspended gesture – but for the way it circles around memory itself. In both Ian McEwan’s story and Grlić’s paintings, remembering is not just a matter of keeping intact but of reshaping: a quiet act of survival, where the past is softened just enough to be bearable.

Finally, Imaginary Friends (2025) opens the surface altogether. A vast canvas, torn open from the center outward, reveals what might look like a cloudy sky, and within it another image: a playground, glimpsed upon approach. It is the most haunting of the works on view in the show, a vision of memory as loop: nonlinear, recursive, returning to its own point of origin only to alter again. Nothing remains still; everything shifts.

In conversation, Grlić mentioned a concept that resonates deeply with the exhibition — Paul Auster’s notion of the Hotel Existence from his 2005 novel The Brooklyn Follies: an imaginary, dreamlike space created by his characters to escape the heaviness of everyday life. It is a refuge built from longing, suspended between fiction and desire. Perhaps Grlić’s paintings, too, construct such space — not as an escape, but as a way of living with fragility, of finding tenderness within unease. Her Hotel Existence is painted, not written: a place where memory, illusion, and emotion coexist, and where the act of painting becomes a form of staying inside the story even as it shifts and fades.

All works in “Saccharine Idyll” are executed in oil on canvas, expect for the portraits, which are oil on wood. Grlić’s method, though, remains consistent: her backgrounds — pinkish, floral, deceptively soft — are painted in one continuous gesture, a single breath of color, before the subjects and details are layered above. The result is a surface that remembers its own making, a skin of paint that never really settles, where tenderness and tension coexist. As if memory itself had found form.