Time present and time past

Are both perhaps present in time future.[1]

– T. S. Eliot

[1] T. S. Eliot, Four Quartets (London: Faber and Faber, 1943).

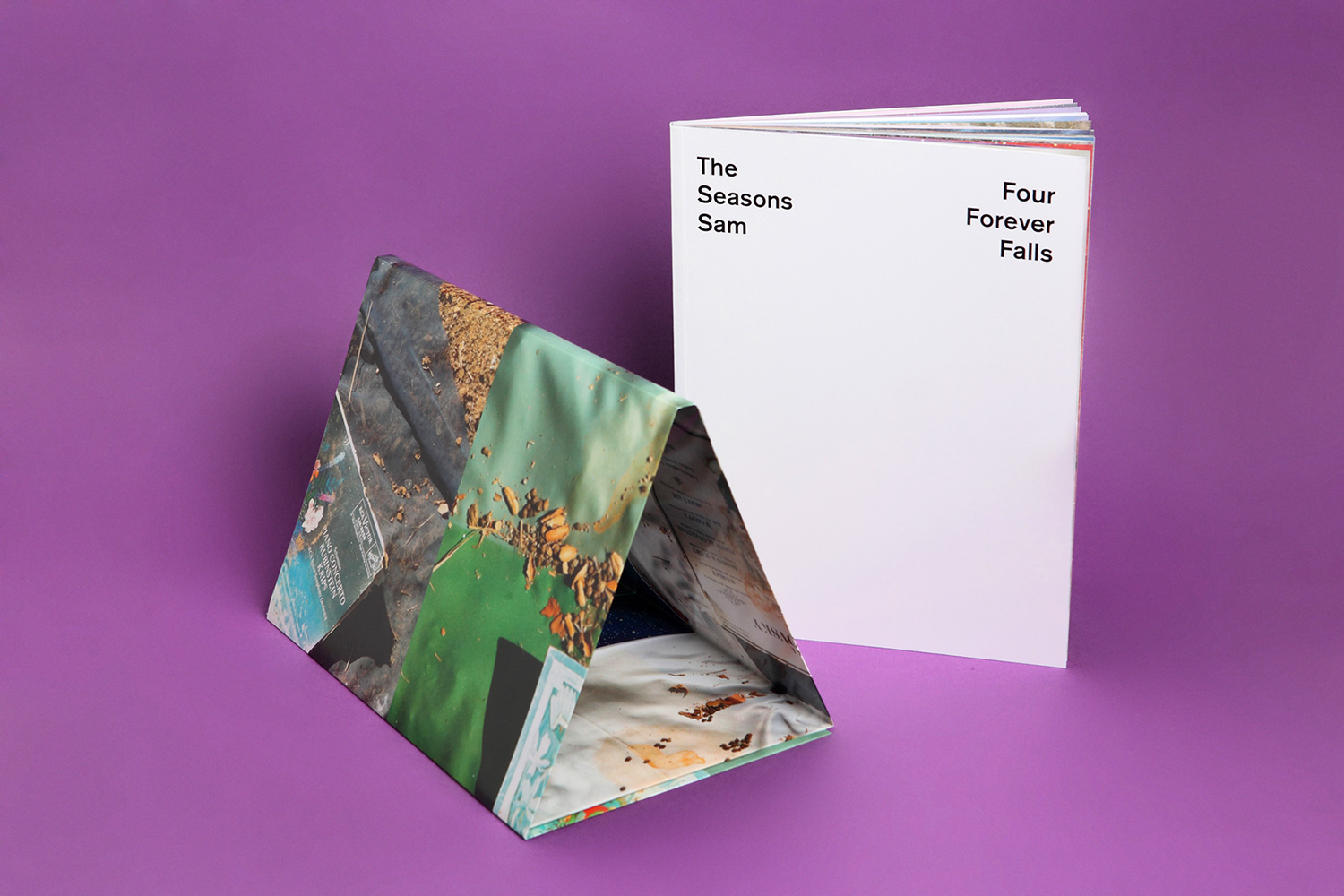

Sam Falls moves with the rhythm of the seasons, where leaves, rain, and sunlight leave traces that are both intimate and monumental. His tenth collaboration with Eva Presenhuber in Zurich traces a path of transformation: gestures rooted in memory and experience stretched outward into dimensions of scale, duration, and environment.

In recent years, the personal and the natural have become inseparable for Falls. Family silhouettes, ceramics holding fresh flowers, and works shaped by exposure to wind and sun speak to life as both fragile and enduring, a rhythm of care that bridges generations. The exhibition invites viewers to inhabit time differently, to feel the slow pulse of seasons and to witness the dialogue between organic forms and minimal structures.

Like a garden folded into the sky, Falls’s practice unfolds outward while remaining grounded, a delicate intertwining of art, life, and the world that surrounds us.

Michela Ceruti: This exhibition marks your tenth collaboration with Eva Presenhuber. It could be a moment of reflection. Looking at the works presented here, do you see the show as a culmination of the ideas you’ve been exploring with the gallery over the past years? And in what way does it open up new directions in your practice?

Sam Falls: Yes – Eva is a core gallerist who occupies the special space of truly working with artists; not just facilitating the productions and exhibitions, but really encouraging creativity and experimentation. Ultimately, I have a conceptual practice concerned with time, exposure, environment, and representation, so change is a constant in my practice. Looking back I can see the work truly shifting through the exhibitions as the exploration progressed and mediums shifted to investigate these concepts. In an art world that finds financial stability in repetition these days, I’m proud to see the dynamic shifts in the shows year to year, and very grateful to Eva for giving me the space and support to change.

MC: It sounds like your collaboration with Eva and the gallery has been almost a kind of dialogue in itself. How do you balance your own conceptual direction with the support and framework the gallery provides?

SF: I think you see this in a lot of artists working with the gallery too. Fischli and Weiss, for instance, have always been my North Star, and so it’s wonderful to see Eva’s mission not falter through the years of showing new work of artists with new ideas. For example, as I’ve grown more interested in working with plants and the environment directly, the work has grown in scale to communicate genuinely with nature – so we’ve done Unlimited at Art Basel four times now, allowing me to make works and exhibit them on a scale too large for the gallery and many museums.

MC: The works in the show weave together elements of the natural environment with aspects of the domestic and the personal. From local flora to season changes, but also symbolic imagery and references to family life. Could you talk a little about how this progressive merging of the intimate and the environmental has shifted in your approach? And also what role personal experience plays in your understand of time and mortality within the framework of your practice?

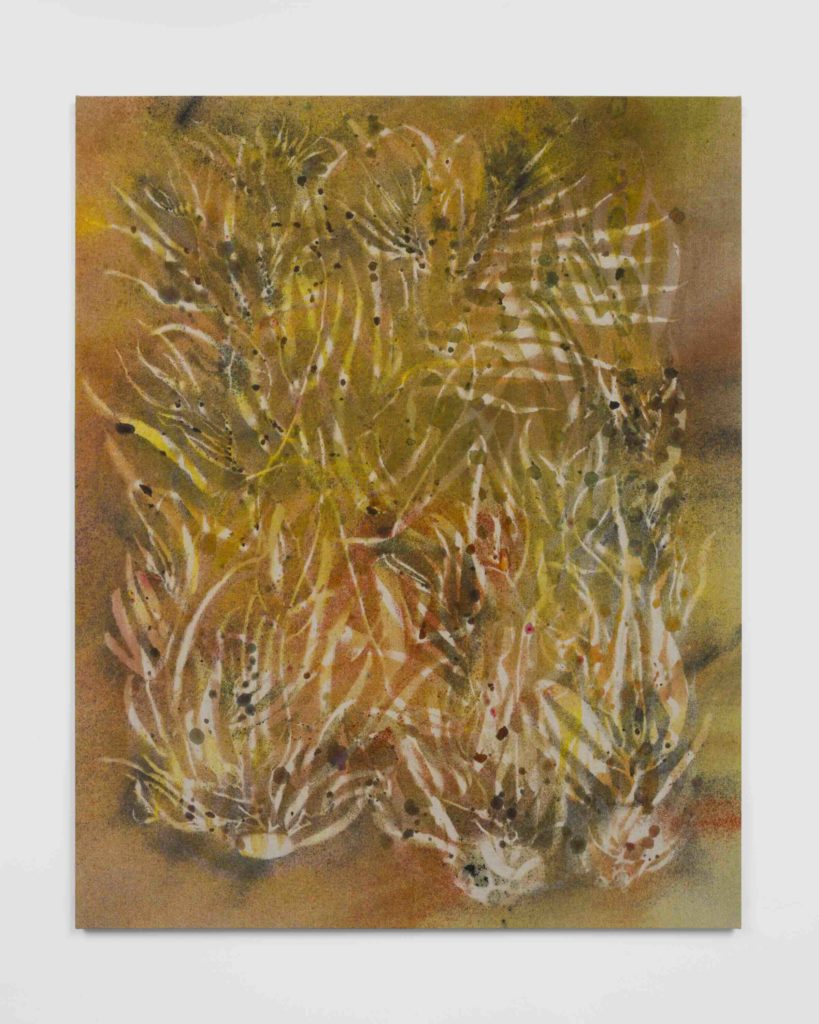

SF: Originally, this method of working came from a conceptual agenda to make site-specific works outdoors – primary source material representing both space and time – rather than mediated through a camera or brush. I initially made works with just one species of plant in the work, like a symbol of geography, iconic or native flora to signify place, such as palm fronds in Los Angeles or ferns in Vermont. The materials and process developed from pursuing the concept; through this I put in my “10,000 hours,” as they say. The more I explored this new “medium” or “process,” the more its potential expanded, such as doing double and triple exposures, working around the world in different climates, etc. Parallel to this artistic exploration of the medium within nature, I became exponentially more intimate with the environment and interested in environmentalism. At the same time, I also became a father, so environmentalism became a deeper concern and entangled in my personal life, considering the state of the world for the future generations. This feeling has only become more pronounced over the years.

MC: How did fatherhood specifically shift your sense of time and your approach to the environment within your art?

SF: This is how, in a way, the environment became a part of my family, inseparable from the way I see the world, and “art as life” really goes both ways. Creating more figurative work using my family as silhouettes feels very natural — the same sense of mortality on a large scale and our intertwined existence. I’ve always felt like the personal is political and so is the natural world –– it is both very politicized and personalized, and so is art. Part of my goal with the domestic quality of some of the new works, such as the ceramics with vases on them to hold actual flowers and be changed by the owner regularly, is to encourage this interaction, as well as continue blurring the line between art and nature, as well as artist and viewer. The ceramic artwork comes from my studio, made with plants from my garden, but the flowers come from the place the work is exhibited and describe the present season, like an abstract macro sundial.

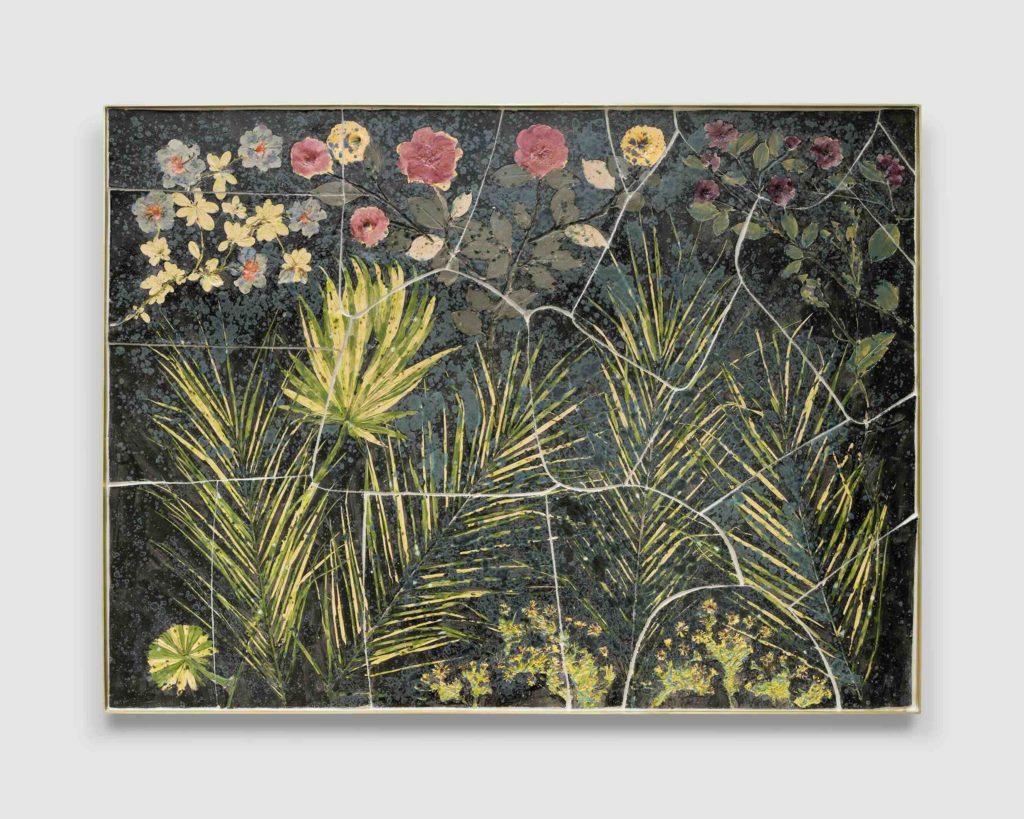

MC: The pieces presented in Zurich integrate natural dyes, withering plant matter, and sculptural elements such as beams or ceramic tiles. They also use more openly symbolic compositions, like that of the Annunciation. Do you think material and iconographic choices invite new layers of interpretation to your work? Or do you see them more about deepening the experiential quality of the works themselves?

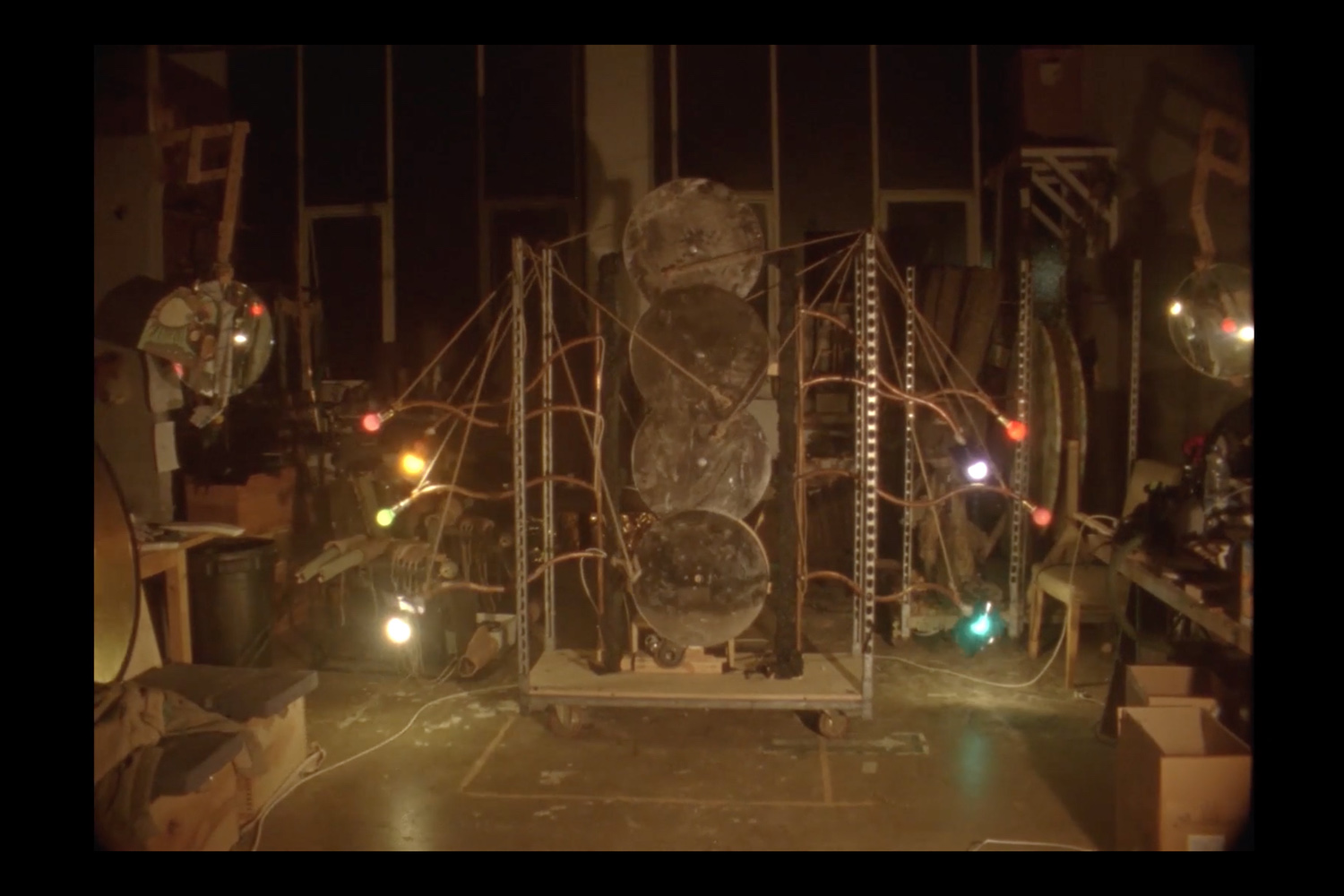

SF: I guess I would have to say the latter, that it is in the interest of deepening the experience of the work for the viewer, which I consider myself to be as well. I don’t make work to have a dialogue with previous work I made, but rather it’s spawned out of that experience and moving forward always. Using natural materials has always been in the genuine interest of making the work more familiar and inviting for the viewer, as well as the process of using sun exposure instead of cameras or darkrooms, or rain instead of printers or projectors. It’s a simple idea, but there’s so much technology and production in art that can often be alienating for the viewer, and while it may be impressive or exciting at first, I find it can also be condescending and cold. So the natural materials offer warmth and an invitation to go deeper, as well as the encouragement hopefully to go farther into the work itself on your own, with your own memory and perception and references. The symbolic or iconographic imagery came in through an interest in formal language, the way I’ve made works building off Donald Judd’s aluminum geometry or Jean Prouvé’s prefab beams. But inserting very organic ceramic tiles within them is to again work with an existing language that’s perhaps chilled and to warm it up again, make it accessible and bring modernism or minimalism into a fresh dialogue with its counterpart of nature.

MC: You mention iconography being secularized or even co-opted by capitalism. Do you see your symbolic references as a way of reclaiming them for something more grounded in nature?

SF: I think iconography has been taken on tour by capitalism to the point where its relationship to religion is its birth but the definition is more secularized. I like the idea of taking it back from consumerism and popular culture and circumventing the baggage of religion to a place more pure: nature, of course. I have a book on Sandro Botticelli’s Primavera (1482) that describes the symbolic significance of each plant pictured, which catalyzed an expanded study of symbolism over the ages with plants. This later brought a full-circle return to college studies of the Renaissance, the symbolism in figures and every gesture. This of course became intertwined with my interest in using the family, and it all came together like this in a way.

MC: Your practice fits somewhere between painting, photography, and sculpture, without being fully defined by any of these categories. I am very curious to know if this kind of blurring of media has always been central to your thinking, or it has become more deliberate as your work with natural processes has developed?

SF: Blurring media has always been central to my thinking, but not as a subject so much as a given — and because artists before my time broke the boundaries down so why worry about it. Actually, inversely, this is what drove me away from photography and toward natural processes – I went to graduate school for art because I had done more art history and theory in university and not much art making – but my interest was merging photography with painting, I guess further blurring the lines. It seemed like it was starting to happen in the early 2000s with abstract photography but always hitting a wall with the darkroom or printers, and ultimately became even more medium specific in a way. So I abandoned all the photographic tools, from camera to chemicals and darkroom, just to use sunlight and time outside – the true definition of photography — on canvas and pigment. So in a way I went backwards to blend the medium beyond where technology was taking it or could go.

MC: Over the past years, your work seems to have grown both in scale and temporal ambition; from large outdoor canvases exposed for days to monumental projects spanning entire seasons, like Spring to Fall, presented at Art Basel Unlimited in 2024. I would love to know how working on such extended timeframes has influenced your relationship with process. Does it change how you think about the life cycle of a work of art?

SF: Well, I believe it imbues the work with a sense of time itself that the viewer can feel, and expanded time is the best time. I was always a fan of Andrej Tarkovsky and the way he did such long takes; there’s a lot of preparation but also a lot of room for chance and environment – this is hard to achieve in art, and the scale itself helps offer more space for this. There’s a line from a David Berman song that says, “People got to shift to geological time.” I think about this often and believe it’s true. The time I spend working outdoors only makes me feel more in tune with what’s essential, and so to combine this with making art brings me to a special place that feels purely creative and true.

MC: I read in the press text for your exhibition that you have always admired landscape photographers like Ansel Adams. And critics often point to traditions like Land Art, cyanotype photography, or even John Cage’s embrace of chance as useful parallels to understanding your practice. I wanted to ask you, from your perspective, which cultural, artistic, or philosophical references have been most meaningful in shaping your practice, and also where do you feel you diverge from those very same lineages?

SF: Yes, Ansel Adams was a big inspiration for me, both in his practice of working and living in nature, as well as the meaningful resonance it had in protecting national parks and raising awareness of the beauty of our landscapes. Robert Smithson was a big influence, specifically his “site/non-site” works, and his trailblazing in turning outwards to collaborate with landscapes. Fischli and Weiss, as I said, for their multimedia approach and dynamic interests, as well as their underlying philosophical commentary.

MC: It sounds like you’re drawn to artists who maintained openness and multiplicity in their practice. What, for you, is the danger when art becomes too narrowly focused or codified?

SF: Robert Irwin is a good example of an artist whose early work I really love — the search for reasons to make art through both experience and philosophy — but then it turns to such a focused point later on in both material and subject that it loses the original life in a way. Same for a lot of the Light and Space artists – the radical and immaterial approach was so refreshing and exciting and influential, but later on it manifested in very material- and production-heavy projects. This reification of the avant-garde is something so many great artists have a problem with from my perspective. I guess it’s not a problem if they shift goals to making money, but that’s why I really respect someone like Andy Goldsworthy – even though the aesthetics I don’t always identify with – his work has remained true to itself/himself – and that justifies my earlier point that time in nature keeps you and the work pure.