For “to love and devour,” Tolia Astakhishvili transformed the site of the Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation in Venice into a layered environment that unfolded as a total artwork. Invited by curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, she spent several months reimagining the architecture of the decaying building. In the conversation that follows, what emerges is a reflection on her process of engaging with the site, on the blurring of hierarchies, and on how embracing disorientation can generate new ways of seeing.

Olesia Shuvarikova: For “to love and devour,” you lived and worked for several months in a 15th-century Venetian palazzo. I believe this space was quite different from the white cube galleries you had worked in before. How has your practice been influenced by engaging with – and living in – this decaying, transitional environment?

Tolia Astakhishvili: Usually, this kind of environment is a source of inspiration for me. Before this invitation, I had at times declined to make an exhibition in a site that was already a kind of place – already a piece of people, a piece of art, a piece of time. When a place feels so complete, it can take much longer to discover what one might still contribute, especially in the usual tight schedule of shows.

In this case, the temptation was just too strong when Hans Ulrich Obrist and Nicoletta Fiorucci told me that I could have the building for myself for four months and be able to do anything to it, almost anything. It was strange to be inside something that influences you and you have to influence it! I had to be careful not to damage what is already there, yet still allow myself the freedom to be able to explore it. I think it was the most challenging project I’ve worked on – I needed to spend lots of time in silence. It felt emotionally quite demanding.

OS: As in your previous shows, you engage directly with architecture. How did you respond to and transform this particular space?

TA: On one hand, I sometimes try to be more passive, to let the space affect me directly, without mediation, allowing it to unfold on different levels. On the other hand, researching the background of the site is also very important to me. While working with Giorgio Mastinu, who delved into the city archives, we discovered that the building had gone through many changes. Long ago it was the property of the Sant’Agnese priory, rented to support a small group of orphan girls. In the 1920s to ’30s, artist Ettore Tito converted it into a studio. Around 1937, it was significantly altered by architect Angelo Scattolin, and in 1973, it was split into two halves: one owned by the Cassa Marittima Adriatica clinic, the other a residential area.

The question became: How do you bring these two units together again? There wasn’t a clear version to return to, so instead of restoring, we created something new. We opened the space so that the different characteristics of each room could be seen – not in isolation, but as part of a whole. I kept sections of some walls, so you could still sense that divisions had been there before. There is an introduction, a hint – fragments of traces. I like it when two or three things happen at once and the space still has a certain fluidity.

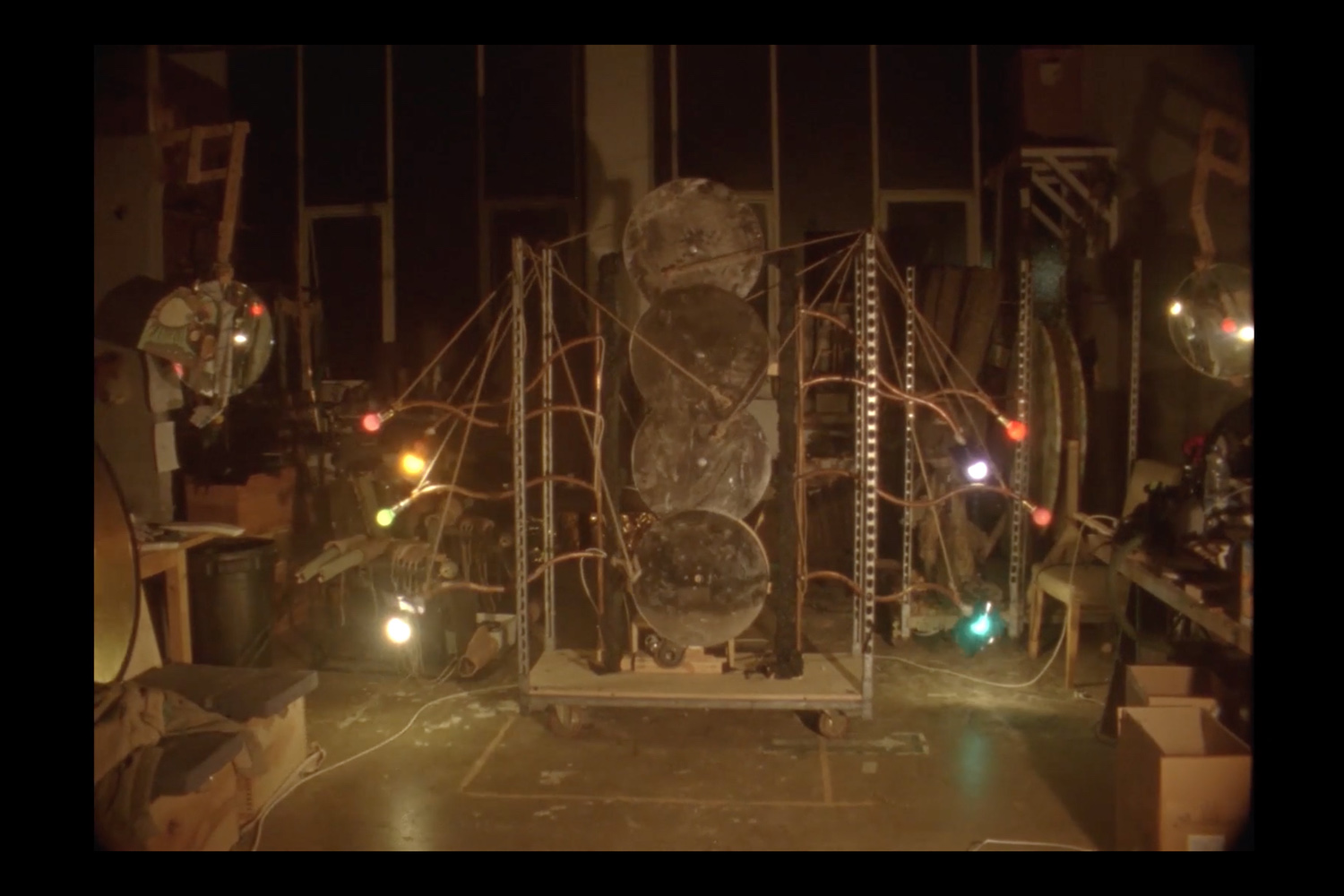

OS: I was thinking about these blurred boundaries between oneself and the space because of the destruction of walls and the possibility to look further beyond. Yet, at the same time, you feel as if you’re stepping into fragments of someone else’s life – almost intruding. Some spaces feel like they are not meant to be entered at all, such as in I Love Seeing Myself Through the Eyes of Others (2025), where we hear voices and see only the shadows of objects inside, but cannot access them. Could you talk about the tension between these feelings in the exhibition?

TA: In this room, I worked with Dylan Peirce on a piece consisting of sounds recorded in public spaces like cafeterias for example. I wanted to create imaginative bridges to the outside, to somewhere else, so the exhibition wouldn’t end at the walls. At first, I thought of leaving the door to this room open so people could enter, but decided against it – opening it would have created an extra physical space, but at the cost of losing a much larger imaginative one. I’m very interested in this potentiality of spaces –– I love preserving our ability for imagination, having a small fragment of something that gives you a ticket to somewhere else.

And then you still come back to the matter. So, it’s not only a journey outside or elsewhere, but also a return to the material world of textures and haptic qualities of physicality.

OS: As you mentioned these little hints pointing beyond the immediate space, it made me think about how you work with temporality. The video on the ground floor, I Remember (Depth of Flattened Cruelty) (2023), seems to function like a memory loop with its distorted, layered images. Elsewhere in the exhibition, several photographs depict people and spaces from different times. Upstairs, there’s a work titled The Last Finger, which echoes your earlier exhibition “The First Finger” at Bonner Kunstverein (2023). How do you work with the time in your practice?

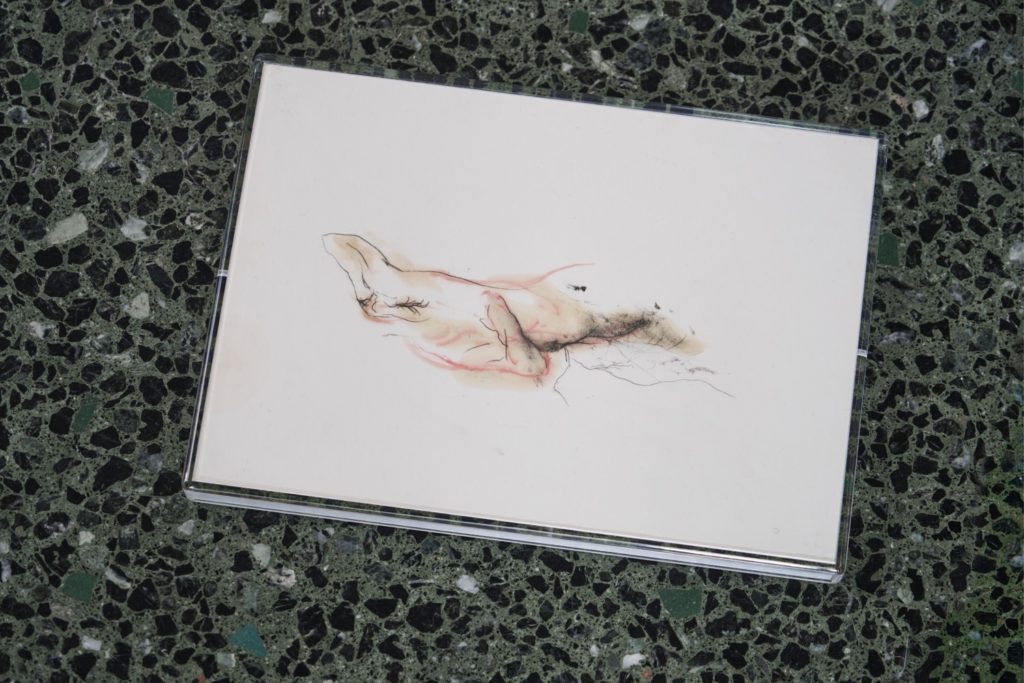

TA: Usually, I don’t differentiate between when a work was made – I use things that I wrote or painted years ago, as well as what I just made yesterday. I also treat the documentation of my shows as material, feeding it back into my work. I find that’s how it works in the real world: we are permanently operating on many different levels, never fully in the now. So, for me, it’s difficult to create something from one linear situation., It would feel as if I were lying – constructing this version of reality that isn’t true. I can see each fragment as being equally important as the others, and all of them together as one work. While working on the exhibition “The First Finger,” I found that hierarchy stemmed from the notion of survival. Our body is hierarchical, as is our mind. If we didn’t have this notion of survival, maybe we wouldn’t have any hierarchies. In order to survive, the body could sacrifice fingers, ears, lips, etc. I try to pay attention to the “insignificant” things that cultures can easily neglect because they are not so “important” for survival. I think about this often while working — how objects can connect and even lend each other strength, also across separate spaces.

OS: This idea of blurred hierarchies remained how I felt when I stood in front of the demolished bathroom wall in your piece My Emptiness (2025): it was as if I was looking into a large mirror reflecting my inner self – the distorted pipes jutting out of the floor seemed to echo my own veins. The boundary between me and the architecture blurred. Looking at the exposed inner parts of the building, I felt as if I had been stripped of a protective shell. How do you work with this sense of exposure?

TA: Many people said that they felt as though they were looking into a mirror, but couldn’t see themselves inside it. I guess it’s just some kind of physical, architectural effect that evokes this feeling. But I also like the idea you mentioned of mirroring yourself and feeling kind of naked there. Sometimes architecture feels like a monologue – it’s up to you whether you leave it that way, or engage it in conversation. If we created this imaginative defensive shell or skin out of the need to detach ourselves from the outside, then architecture can lead us into a different dream, a different kind of state. For me, it’s almost like a playground.

OS: As you mentioned, architecture can transport us into a different state. I wanted to talk about these moments of transition, the in-between state you create – like in one of the rooms lit by dim yellowish light, where the abstract metallic pieces by Thea Djordjadze are scattered across the floor among something as ordinary as footballs.

TA: This environment here serves as a bridge into a state where reception is more open. Rather than a stage, it is a substance of its own as opposed to a room meant for representation. You can treat it like a non-linear film in space: go back and forth, up and down, or take it very slowly. It’s absolutely your choice how you engage with it.

OS: I was thinking now about how film is always the product of many people’s work. You also collaborate with several artists, including family members like your father. Why is it important for you to move beyond a solely individual perspective?

TA: I like bringing people together and creating conditions for things to happen. I also find it interesting that the space – like everything I have done – is not something invented from scratch. Everything is a collaboration with, or a memory of, someone or something else. I’ve seen things and I’m influenced by things. I still try to control everything, and I feel the tension in controlling, but I also feel how much I sometimes really love to get confused. As soon as you involve other people, it becomes a different universe. Every artist is their own planet – I like to arrange the works in such a way that it feels like a real coming together. It is particularly exciting to work with artists who allow for this fusion between works to occur.

OS: So, by letting go of control and exchanging with other artists, you allow something more to emerge.

TA: Yes, that’s a bit contradictory, because I plan a lot in advance. But I also let myself totally get lost. It’s not even that I try to get lost, it’s just what happens every time. When I’m lost, it becomes more real because the connections between me and the things slowly become stronger, and I discover more. I think it’s like when you are traveling with a plan – you know where to go, but you act from your own perspective. But when you’re lost, you see everything differently. Something you haven’t seen before suddenly appears. Interactions with people also become different because you’re more vulnerable. But because you’re vulnerable and more dependent, you’re more open. So, then it becomes something new – moments that I didn’t expect to happen, happen. You send something out, it comes back to you, and something new is born.