I arrived in Aspen, Colorado, after an unexpected detour – diverted to Grand Junction Airport and landing safely on my second attempt. From this altitude, the Rocky Mountains revealed themselves with fresh clarity: not merely majestic, but loaded with symbolic density – a geological threshold where extraction, retreat, and renewal converge. The town of Aspen exudes a strange kind of glamour: a place where affluence meets experimentalism, and high-end tourism intersects with cultural urgency. At the heart of this paradox sits Aspen Art Museum, a shining beacon for contemporary, housed in a masterpiece by Shigeru Ban. The building’s 3,000-square-meter hybrid structure of concrete, steel, and wood integrates seamlessly into the town’s brick-lined streets, its wooden strips echoing the surrounding masonry and casting mesmerizing visual effects. Here AIR – Aspen Art Museum’s groundbreaking initiative – has taken root.

AIR is a year-round program, a festival-think tank-exhibition hybrid that seeks to foreground artists as protagonists in shaping the cultural, ecological, and technological dilemmas of our time. Rather than simply inviting artists to respond to a site, AIR positions Aspen itself as a set of conditions — historical, atmospheric, political – to be interrogated and reimagined. Its inaugural edition brought together figures like Matthew Barney, Paul Chan, Cannupa Hanska Luger, Jota Mombaça, Mimi Park, Sophia Al-Maria, and Apichatpong Weerasethakul, as well as theorists and writers including Jaron Lanier, Zoë Hitzig, Aria Dean, and Jamieson Webster. “We don’t collect art, we help create the atmospherics for new thinking and processes,” notes director Nicola Lees. “Aspen Art Museum is remote from the major nodes and noise of the art world, so when artists come here, something happens to them on both a conscious and subconscious level – the quiet, the mountains, the history here, it all shifts something inside them.”

The first morning began at dawn inside the Aspen Chapel with On Blue, a performance by filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul and composer Rafiq Bhatia. Inspired by moments of awakening and sunrise, the piece layered ambient sounds and orchestral textures with hypnotic film sequences, creating an atmosphere suspended between the physical and spiritual. The quiet lingered into a compelling conversation between Los Angeles-based artist P. Staff and psychoanalyst Jamieson Webster, who explored the entangled themes of dream, death, and the unconscious as collective space in a time of ecological and psychic polycrisis. Webster noted: “I’ve been working on the connection between breath and death since the pandemic. How scared, and so much meaner, we’ve become since experiencing our interdependence on air. I hope we can mourn this loss of innocence. P. Staff’s brilliant work is a North Star, reaching how we might do so.” By afternoon, Brazilian artist and writer Jota Mombaça activated The Muted Saints – a site-responsive opera in three acts staged along the laminal edges of Hallam Lake. The piece blurred human and planetary timelines, collapsing myth, memory, and material resistance into a single, slow movement. At dusk, the rooftop of the Aspen Art Museum transformed for Sophia Al-Maria’s We Slip and Sway Away – a haunting sonic performance that folded sound and gesture into a meditation on movement, grief, and memory.

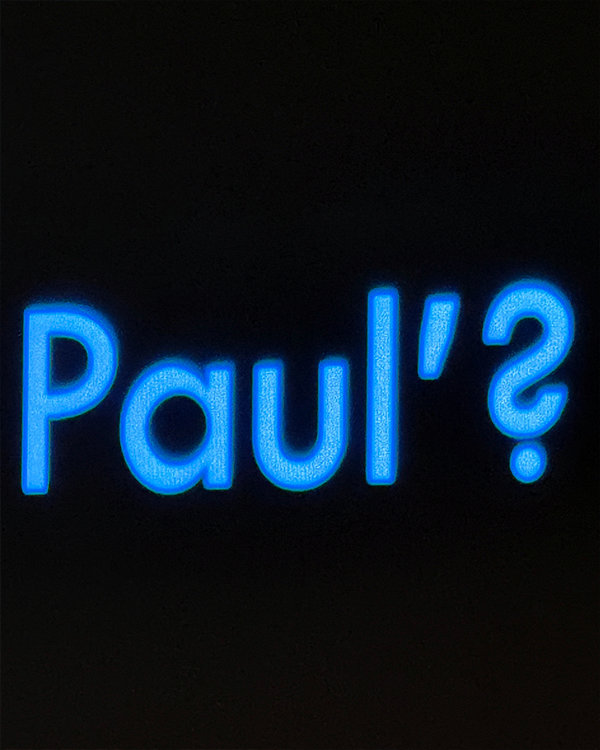

The following day, at the Aspen Institute, Paul Chan presented Paul’ – what “he called a “synthetic self-portrait.”” Part performance, part algorithmic fugue, the work wrestled with the dissolution of subjectivity in an age of simulation. Chan also shared insights from the AIR Retreat – a closed-door, artist-led gathering of over thirty thinkers – highlighting a particularly uncanny exchange: “machine talking to machine.” This set stage for a dynamic dialogue between poet and economist Zoë Hitzig and British neurologist Anil Seth, who explored cognition at the border of human and artificial intelligence. Together, they questioned how machine learning systems are reshaping our perception of self and the world, and what this might mean for language, art, and legacy. As Hitzig put it, the fear lies not in the machines themselves, but in how little we understand the structures shaping our reality. In sharp contrast, curator Hans Ulrich Obrist introduced filmmaker Werner Herzog to a standing-room-only crowd. Over six decades of visionary work, Herzog has chronicled the mythic, the marginal, and the metaphysical. His keynote probed the notion of “ecstatic truth” – an idea that transcends factual accuracy in pursuit of poetic resonance. In a world increasingly governed by algorithmic logic and synthetic image-making, Herzog’s call for the irrational, the intuitive, and the sublime felt urgent and clarifying.

That evening, Matthew Barney’s TACTICAL parallax was staged at McCabe Ranch. Combining sequences from his most recent films, Redoubt (2018) and Secondary (2023), the works juxtaposed football, hunting, and topographic violence into a kind of symbolic clash – a meditation on American masculinity, conquest, and choreography. “Football is a reification of war,” Barney stated. “It structurally is like a medieval war and it’s fetishized in that in the culture. The American mythologies of war include that initial colonizing of the West.” Rather than providing resolution, Barney’s piece functioned as a threshold – a hinge between AIR’s speculative energies and its closing reflections.

The final day began quietly at the library of the Aspen Center for Physics, where South Korean interdisciplinary artist Mimi Park unveiled Melody from Stomach, a new two-part installation occupying two rooms on campus. Curated by Daniel Merritt, the Bethe Library housed the main piece: a floor painting made of hand-dyed fabric scraps, buttons, custom gemstones, and dried flowers. Using the Night Sky app, Park recreated the constellation that was directly overhead when she began the floor work – Auriga. In a nearby closet, she created a silvery expanse of biodegradable glitter adorned with soldered stardust sculptures. On a shelf, a series of small handmade sculptures invited visitors to take one and leave something new in its place – a quiet ritual of exchange. Immediately following, artist and writer Aria Dean engaged in a compelling conversation with Courtney J. Martin, director of the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation. Their dialogue centered on Off-Modernism and what art objects can do – and have historically done – for their creators and audiences. Dean traced artistic innovation across poststructuralism and Afropessimism to explore how aesthetic and ideological framework shape, and are shaped by, the ontology of Blackness and the social life of art. Later that afternoon, the Aspen Art Museum rooftop came alive once more for a major musical performance by Caroline Polachek. Known for her genre-defying sound and captivating energy, Polachek delivered a sonic crescendo that felt like a closing invocation – a luminous, emotional charge echoing through the valley.

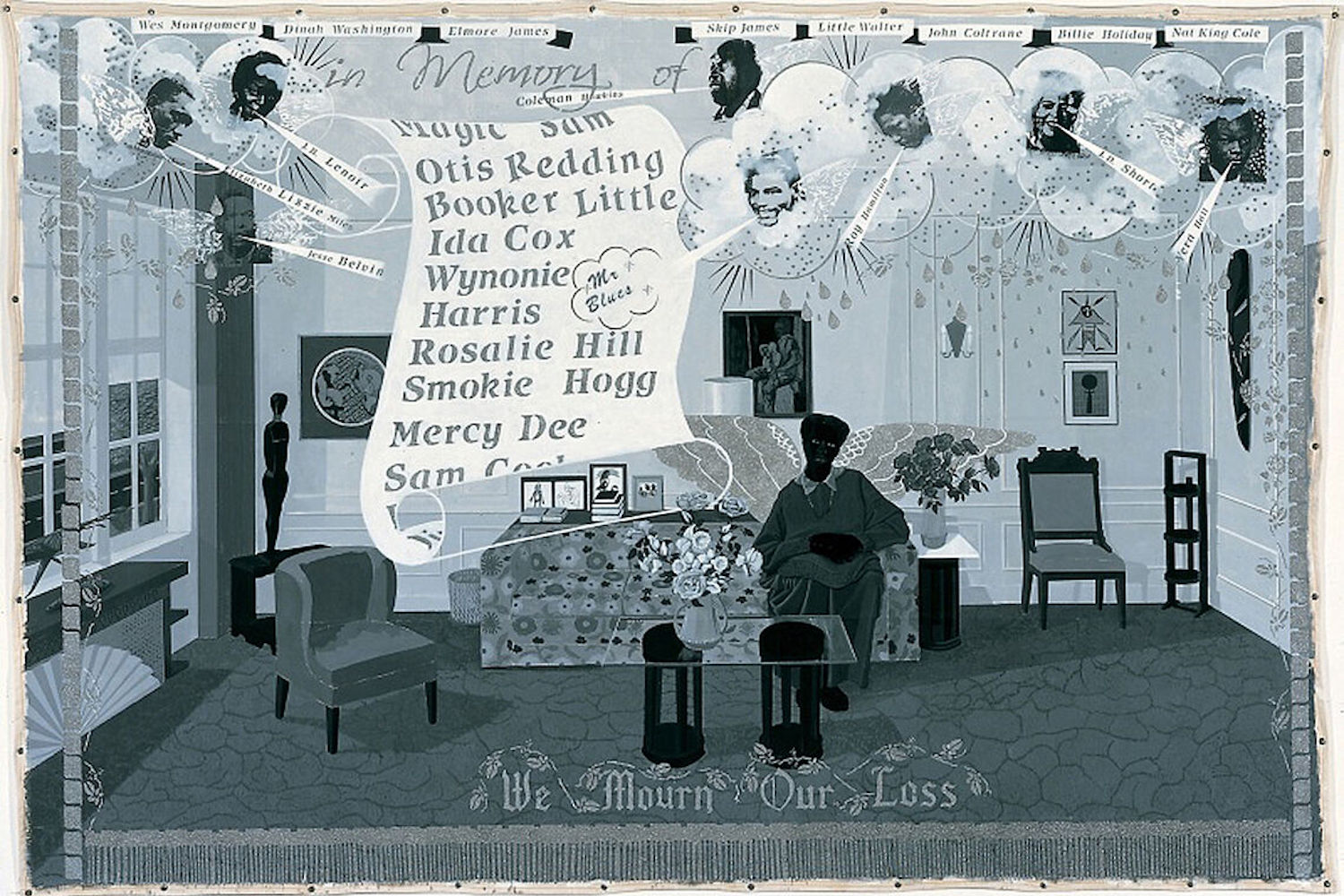

The final act of AIR came in the form of a deeply resonant conversation between artist Glenn Ligon and curator Thelma Golden. Their dialogue traced a shared history of collaboration, from Ligon’s inclusion in Golden’s “Black Male” (1994–95) at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, to her curation of “Stranger” in 2001 at Studio Museum in Harlem. The exchange was more than retrospective: it was a meditation on friendship, community, and how personal bonds shape public culture. “At a lecture many years ago, the feminist scholar bell hooks said your work will take you places that you might not ordinarily go,” said Ligon. “I trust artists to take society places it might not ordinarily go – and through their work, imagine futures that we might not be able to imagine.” For more than fifty years, the International Design Conference in Aspen (IDCA) promoted bold collaborations between art, design, and commerce. Today, AIR picks up that legacy – not by replicating it, but by redefining that. In Aspen, artists are not only shown, they are heard, supported, and trusted to lead.