The latest iteration of Seth Price’s video Redistribution (2007–ongoing) is currently buried in the deepest, darkest corner of 15 Orient in New York — in a hot room with peeling paint on the walls, cigarette smoke seeping through the floorboards, and an AC unit fighting for its life. Getting there is simple, in theory: duck through a side door on Cortlandt Alley, slip around a loading dock, climb a flight of stairs past a textile factory, and walk through a labyrinthine show of another artist’s work.

Even then, once (technically) inside Price’s exhibit, there’s still a large penultimate room to decode — three tables arranged with his works. On one, Price’s published texts, mainly bound; on the next, his as-yet-unpublished texts in manuscript form; and on the last, the ingredients and paraphernalia required to make and enjoy a cup of tea. All of it lit by cylindrical lamps enveloped in synthetic fabric printed with scans of human skin.

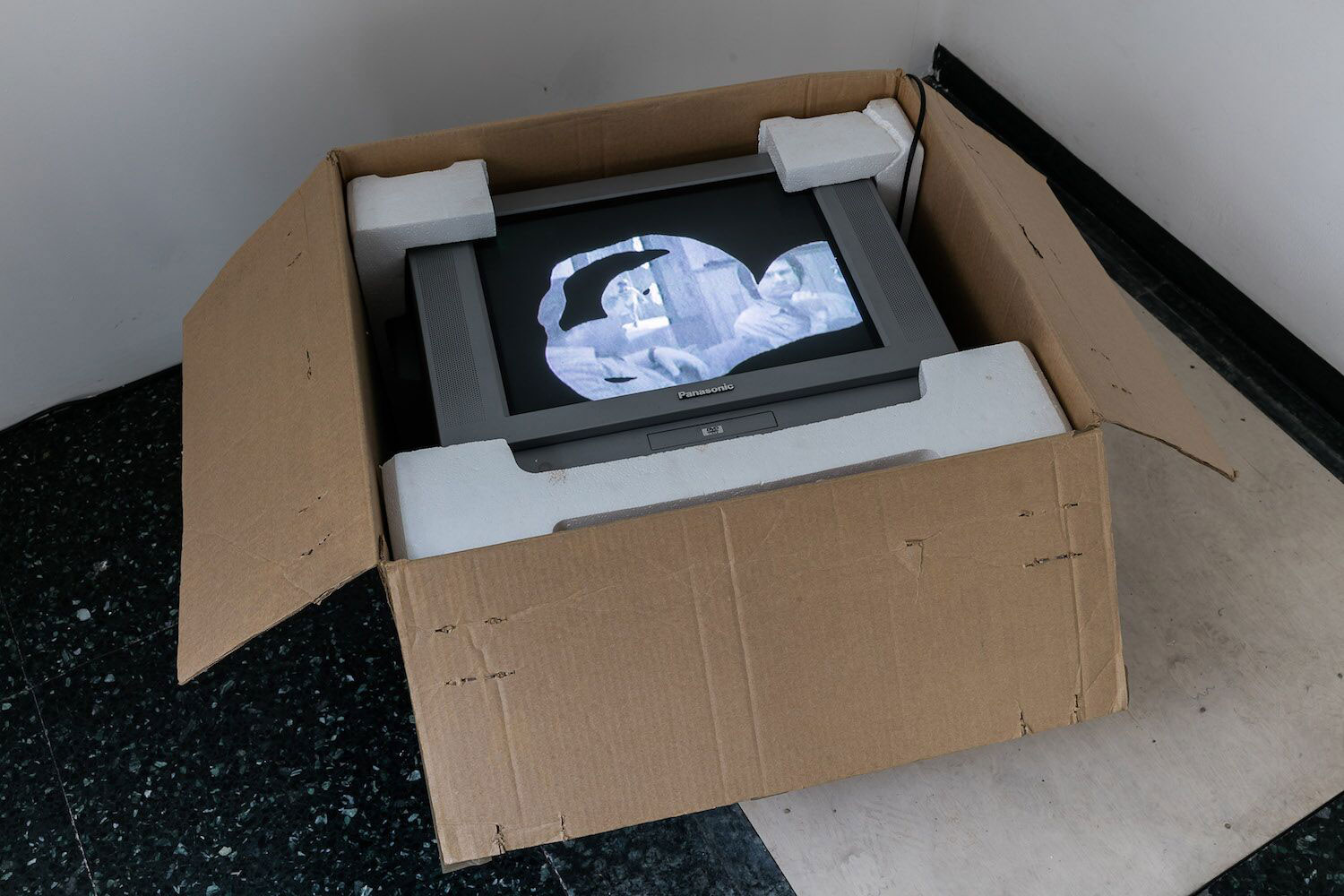

Only then — after all that — in the final room: the video.

In literal terms, this version of Redistribution – installed for the first time as an exhibition in the United States – forces us to consider the video last. It’s a gesture that calls attention to the primacy of context, to the currents of place and time that inform art’s mechanisms of production and reception. More figuratively, the journey of finding Redistribution is a very roundabout way of arriving at an artwork that itself takes a very roundabout (read: endless) course to become one. Based on footage taken from the artist’s lecture at the Guggenheim Museum in 2007, and continually updated in the years since, Redistribution works in a collage-type essay film format to contextualize Price’s practice through an impossible range of art and culture — from the Lascaux caves to Bruegel’s 1560 painting Die Kinderspiele to copyright law to wine connoisseurship (and much, much more). Price’s voiceover drives the whole thing and, though the pacing is unhurried — at times even drawn-out — the film still moves too quickly for most of its abstruse points to ever settle in.

Yet Price invariably returns to ideas about plasticity, as he has in previous versions of the video, about an object’s ability to redefine itself as it’s recontextualized, even while remaining “the same.” Although he gets most explicit in these terms when talking about the internet or software — “essentially in flux, always pointing to the next version and the last version, but somehow understood to be the same over time” — it’s clear he could just as easily be referring to his own art practice generally, the Redistribution project specifically, or even himself.

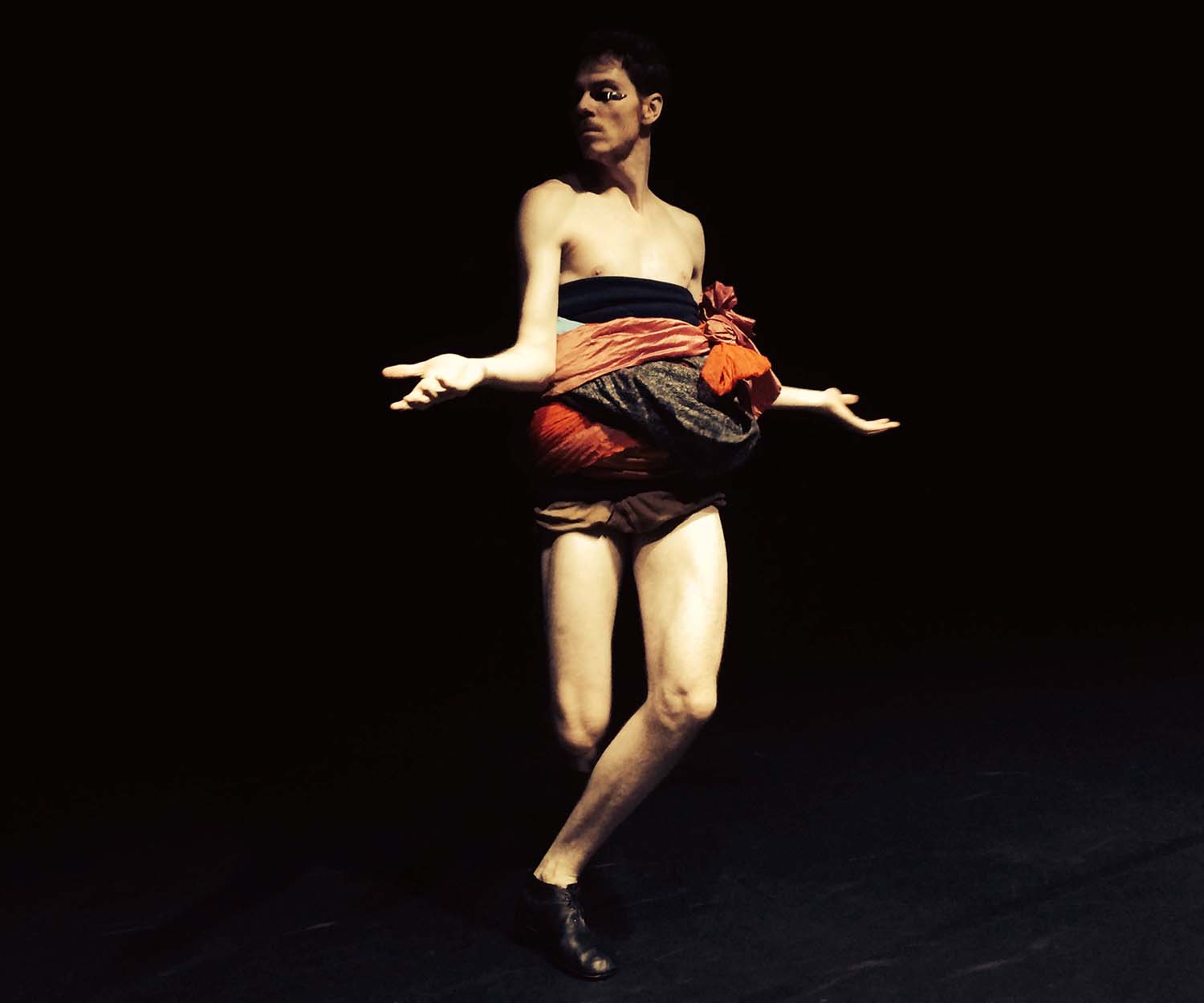

What’s new about this version of Redistribution, however, is Price’s willingness to be himself on camera, or at least present convincingly as such. In previous iterations, Price appeared mainly off-screen, as a cold, didactic narrator, often using a woman’s stern, measured voice as a surrogate for his own. His voice – whether by proxy or not – was unreliable and subtly manipulative (an echo of his 2015 autofictional novel Fuck Seth Price), grating in its ambiguity, and certainly one that lived up to John Kelsey’s quip of Price being “one of the original trolls of contemporary art.” When he did appear on screen, the moments were swift, staged, and impersonal – snippets from his Guggenheim lecture, documentation of an artist portrait photoshoot.

Those elements remain, but now, we also get to see Seth Price in the flesh –– questions of person/persona muted to a degree –– living and breathing, moving through the world. In one instance, he’s riding a child’s bike down a dirt road near his house in the woods, musing in the voiceover on Hinduism’s four stages of life (specifically the third, “forest dweller,” stage). In another, he’s in his backyard, at work on a wood sculpture (a newfound interest), speaking enthusiastically about working with a material (wood) that’s far less forgiving than the one his video has so coolly revered for almost two decades (plastic). And in yet another, Price talks with his Gen Alpha daughter, for the most part listening as she offers offhand insight into the present moment (“It’s no longer possible to not be afraid”) and resists Price’s push toward categorization (that’s more of a Gen Z thing).

If earlier versions of Redistribution were defined by cold “truth,” by its intention (sincere or not) to make a point, these latest additions thrust it toward a more playful, endearing space. The diaristic interventions recall the warm lens of Jonas Mekas – the camera records soundbites, of course, but also moments of silence and indecision, the sparkle of thought. Far from force-feeding us axiomatic, oft irony-laden decrees (“Distance is the oxygen that feeds the flames of desire,” a personal favorite), these intimate moments are dealt sparingly and kept open. They make us consider love, or nature, or time, all things recognizable and real, and also without form.

Which brings us back to the installation: to the room with the tables, and the past and future texts, and the tea; to the cylindrical lamps that help us see, whose covers depict magnified, high-resolution photos of human skin. What do we make of all this? Perhaps, like the recent additions to the video, we can consider it something of a diary, a mapping of time, a recognition of the natural. The texts are too many and too long to be associated one-to-one with the video. Instead, they become signifiers. Written work aggregated and redistributed as singular artworks, bootlegged for a new purpose. On one table, the past, on the next, the future. And the third table… the tea… something to be enjoyed… to slow down with. Is that now?