In 2020, Marcus Rashford’s campaign to extend free school meals during lockdown didn’t just shame the Conservative government into a U-turn, but also exposed the deeper hypocrisies of a nation where the gesture politics of “Clap for Carers” masked a refusal to materially support the very communities doing the caring. Rashford, a young Black footballer, was met with dismissive calls to “stick to football,” as if his intervention into policy revealed a national unease with issues of care, class, and who is deemed deserving of protection. The contradictions and tensions around Britishness, between symbolism and material need, between national pride and structural neglect, are explored in Okiki Akinfe’s solo show, “Where the Wild Things Are,” at Ginny on Frederick in London.

As a British-Nigerian woman who grew up in Essex, Akinfe is acutely aware of contradiction. Essex itself occupies a liminal space near London, often shaped by classed and racialized assumptions, and caricatured through media and reality TV shows like The Only Way Is Essex (2010-ongoing). Akinfe’s work mines these complexities, resisting the flattening narratives so often used to define identity, and renders them through satire, absurdity, and references to children’s cartoons. The title of the exhibition is borrowed from Maurice Sendak’s 1963 children’s book Where the Wild Things Are, as Akinfe reconfigures school playground games, economic precarity, and media stereotypes through drawing and painting with humour and painterly precision, creating works that are both autobiographical and structurally political.

“My mum works in children’s services, my dad in mental health,” she says. “Hearing about kids going hungry, or government campaigns that printed anti-knife slogans on chicken shop boxes [in 2019, The Home Office was criticized for printing more than 321,000 takeaway chicken boxes as part of its #KnifeFree campaign]… I wanted to respond to all that in a way that was honest, satirical, and a little absurd.” That tension sits at the heart of her largest painting, Scramble! (2025) titled after a playground game where a coin is thrown, as someone shouts “Scramble!”, and bodies dive in. The prize is lunch money, or sometimes a Kentucky Fried Chicken £1.99 snack box. “It only happens in schools with free school meals,” Akinfe says. Installed low on the wall, Scramble! is a large-scale concave canvas that envelopes the viewer in its frieze-like composition. Painted shoes arc mid-air, limbs twist, the energy is frantic, and the painting is like a cartoon fight cloud, akin to those in Looney Tunes, or Road Runner dust trails.

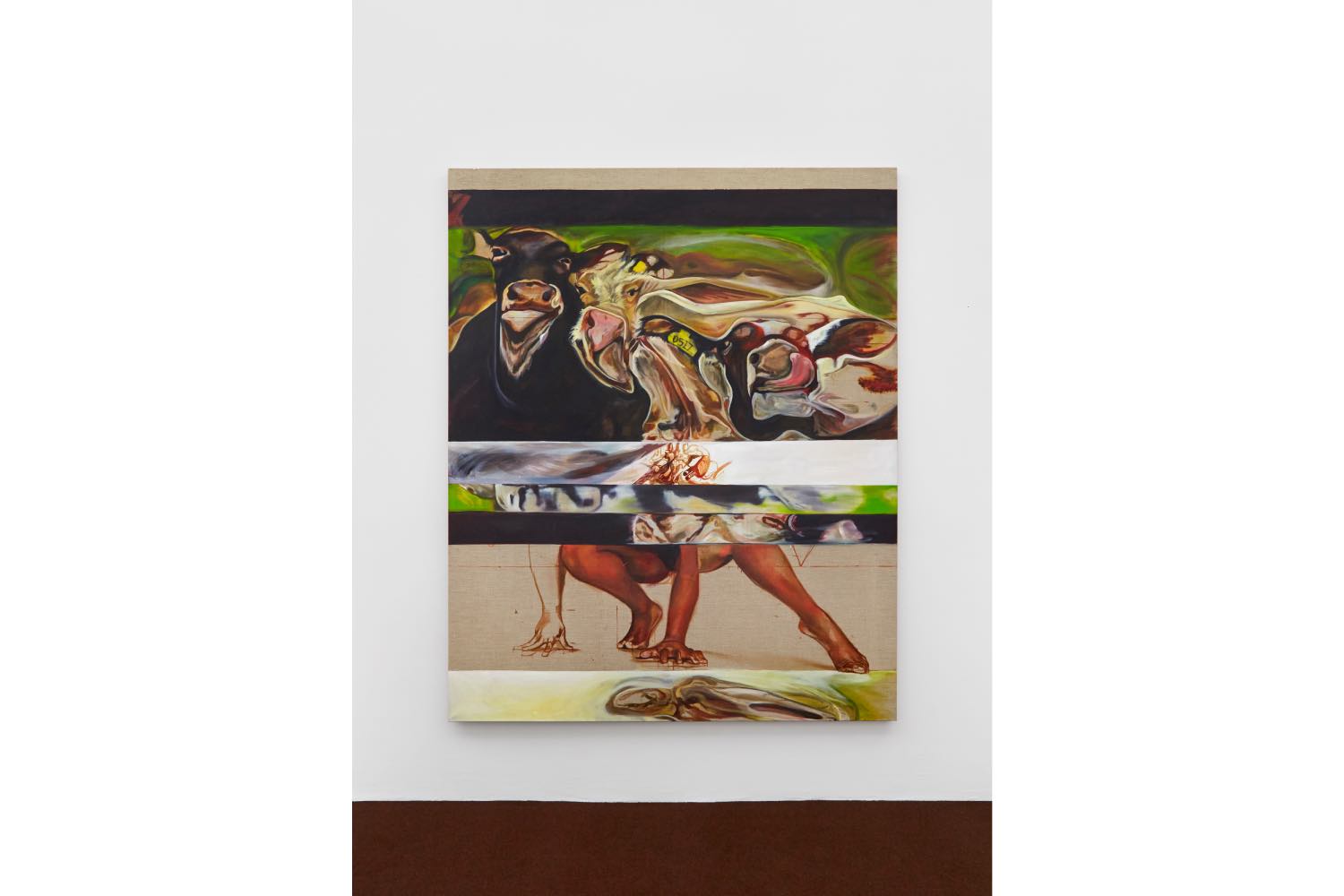

Throughout the show, Akinfe draws on the visual language of comics books and anime. In one framed A4 pencil drawing, smoke swirls behind a vanishing figure, as the comic-strip format is structured and rhythmic. Akinfe’s technical precision and command of painterly language is distinctive. One large-scale painting, She’s an Absolute Cow! (2025) makes this clear. Fragmented into eight uneven vertical slices, the composition shuttles between grotesque cow heads and lurid green pastures before descending into the awkwardly crouched, partially rendered body of a human figure. It’s garish, unsettling, and the insult in the title is both literal and metaphorical.

“There’s this idealized notion of the British countryside,” Akinfe says. “I kept seeing posters growing up of hills, cows, trains, and slogans like ‘This is Great Britain’ That’s Essex too, in a way. I was also thinking of Picasso’s bull studies and how far you can push a figure before it’s abstract, or recognizable again.” Here, the cow is many things at once: a nod to Britain’s agrarian self mythology; a gendered slur hurled at women; and a caricature of Essex femininity, with its fake tan and tabloid infamy.

Her compositions are “messy,” not in a pejorative sense, but in the sense of being honest to how contradictory and frustrating identity can be. In a country that flirts with monoculture while marketing itself as multicultural, Akinfe’s paintings act as a visual counter-archive: one that insists on dissonance and satire. What makes Akinfe’s visual language compelling is how visibly provisional it is. The perspective lines are left in place, gaps remain unpainted, and ghost forms are rendered as if the painting is still working itself out. And in doing so, makes visible the labor of identity construction itself. This rejection of a clean or polished canvas is not just stylistic; it’s a critical position against the simplification of selfhood.