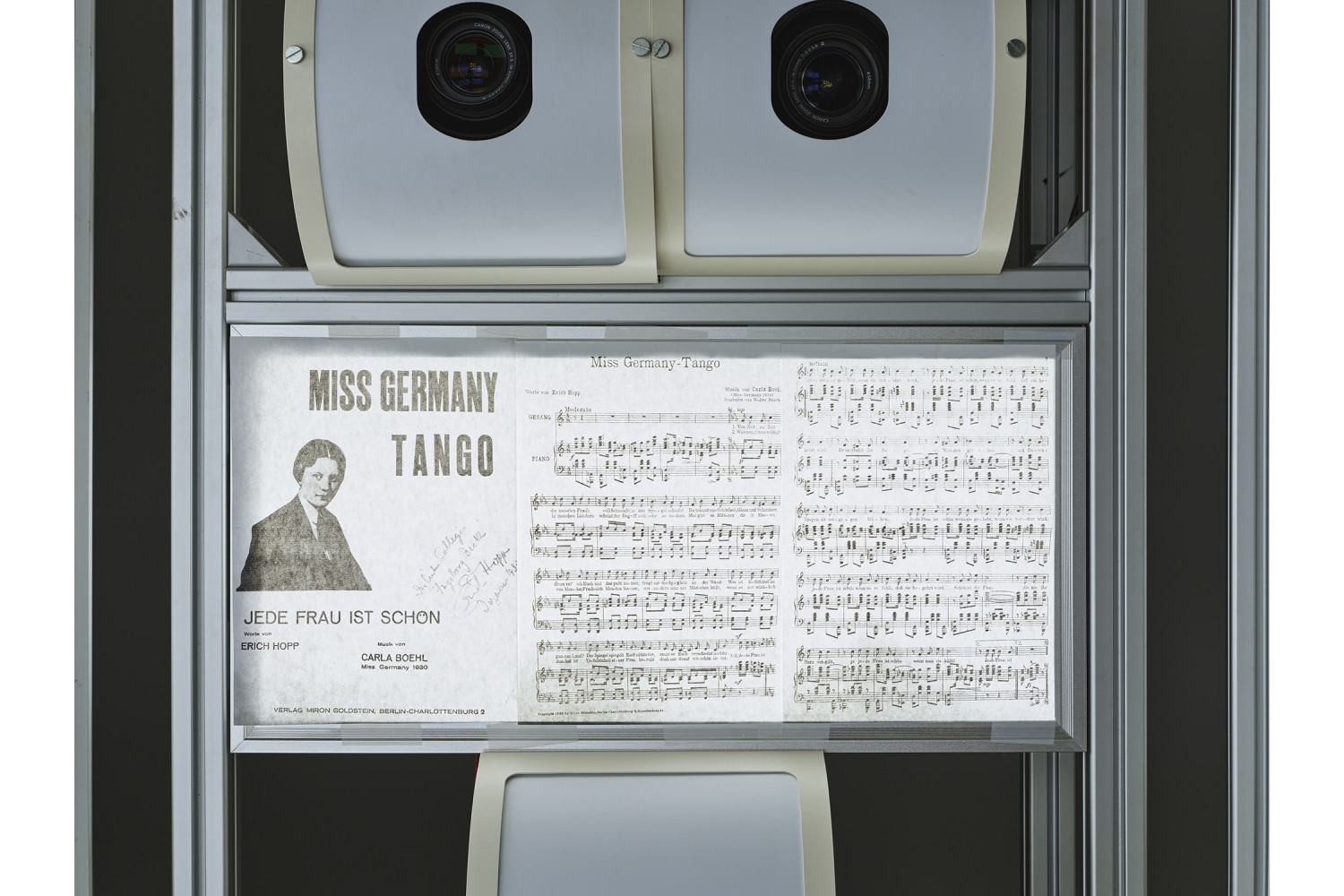

Performativity is essential to Nikita Gale’s transdisciplinary practice, which revolves around a perversely anthropological interest in political spectacle, with its more-than-human scale but all-too-human organization. The social contradictions of spectacle take center stage in “NOSEBLEED,” the Los Angeles-based artist’s debut solo exhibition with Petzel Gallery in New York. Gale’s work reveals the prowess and fragility of contemporary fascism through images of the types of stadium spectatorship that it simultaneously brings forth and is conditioned by.

Upon entering the exhibition, I was immediately confronted with NOSEBLEED 15 (all works 2024), a Midjourney-generated image of a presumably crowded stadium seen from an aerial perspective. The opaque image — in which I can only identify rows of seats with bodies occupying them and two headlight beams that pierce through the composition — is so subdued by its black-and-white quality that it appears to me as a semi-latent image, as if the original image never quite made it through the color transfer process. Despite its murky appearance, the image immediately establishes a commanding atmosphere, thanks to its matte finish and placement high above eye level.

The rest of Gale’s works are arranged in a tight and compact presentation. The installation work NOSEBLEED sets the scene. One part of the demanding apparatus is a larger-than-life, bird’s-eye image of a stadium filled with audience members engrossed in a state of excitation, printed on vinyl that carpets the floor. Faces are not legible, and therefore any differentiation of individuals is negligible. This sweeping depiction of losing oneself within a collectivity is reflected and refracted by a mirrored wall under a spotlight. The image on the floor is far more distorted yet feels intimately connected to me; its reflection, observed from a vantage point that is distant and unengaged, hovers over me with a clinical aura. The doubled presence of the same image speaks to what it means to be politically implicated in a public setting, which is to be both personally engaged yet constantly risking the loss of self.

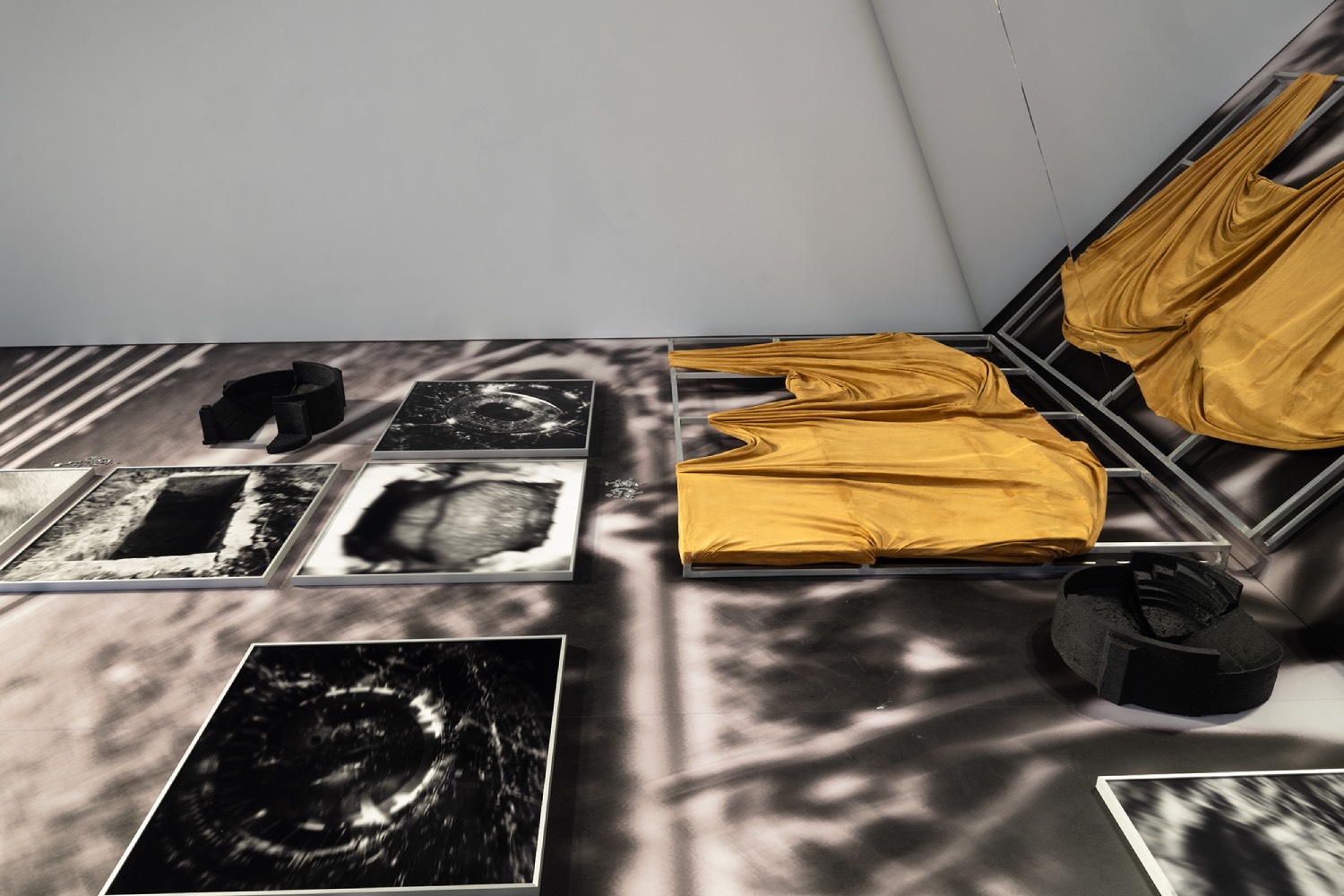

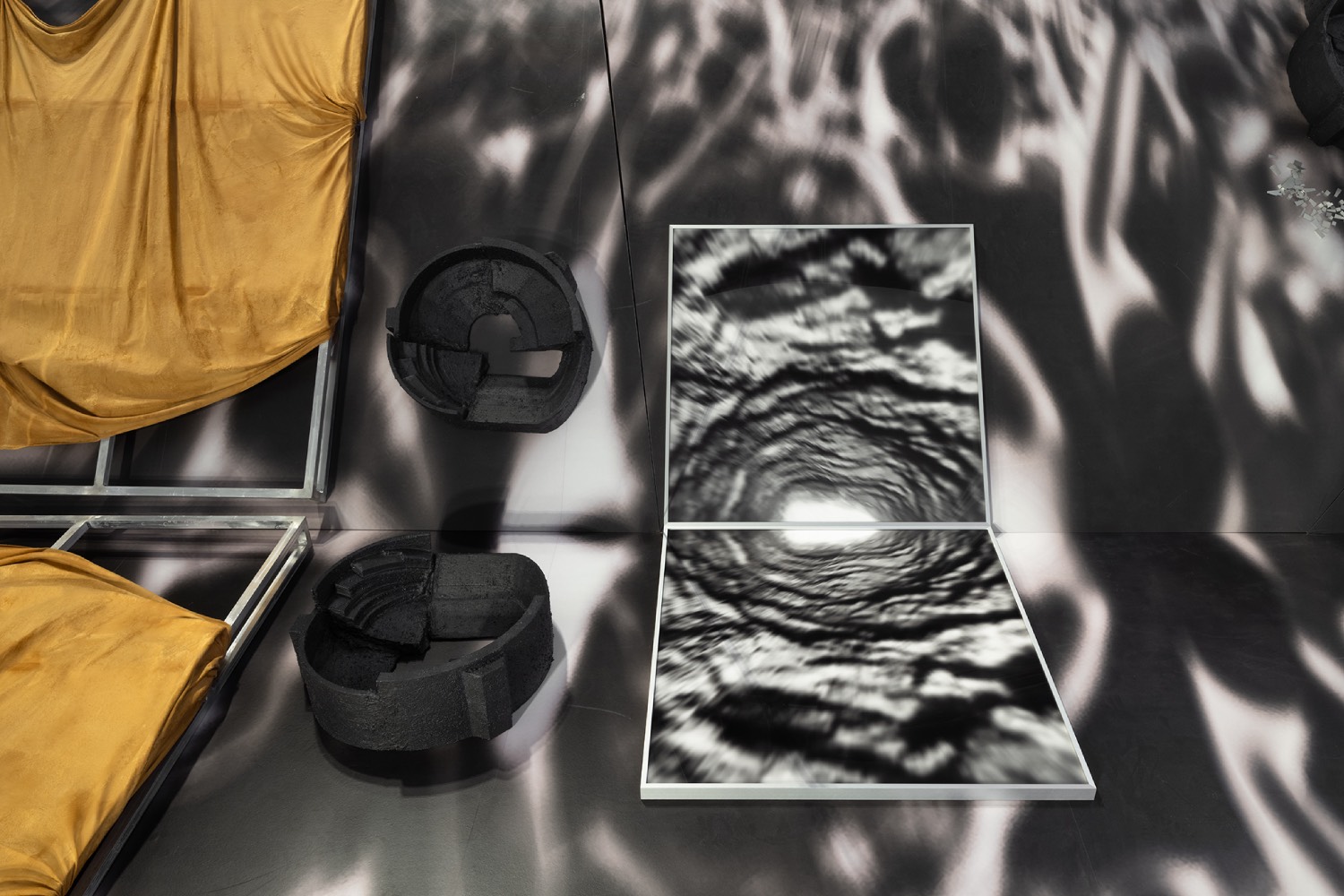

More generated images of the same stadium seen from an aerial perspective — perhaps captured by a drone — are positioned on the vinyl floor. These images give the impression of architectural studies of the urban environment that envelops the fictional stadium.NOSEBLEED 7 and NOSEBLEED 2 almost mirror each other, with the former darker and the latter brighter. NOSEBLEED 1 appears to capture the moment following NOSEBLEED 2. However, all images are scattered on the floor, creating a sense of temporal disjuncture, reflecting the default mode of governance in today’s authoritarian regimes. In contrast, NOSEBLEED 4 and NOSEBLEED 8 are completely out of focus, more akin to abstract sketches of light and shadow. Gale’s disjointed and ghostly images, generated by artificial intelligence, are complemented by four architectural models of arenas in ruin and two velvet-on-aluminum wall works that suggest stage curtains. Together, these elements violently assume their status as proxies for the physical architecture of rising fascism.

The artist also briefly pivots to the insidious synergy between necropolitical machines and resource extraction, as confirmed by images of a deep grave in NOSEBLEED 9, the tunnel of a Carrara marble quarry in NOSEBLEED 11, and a copper mine in NOSEBLEED 14.

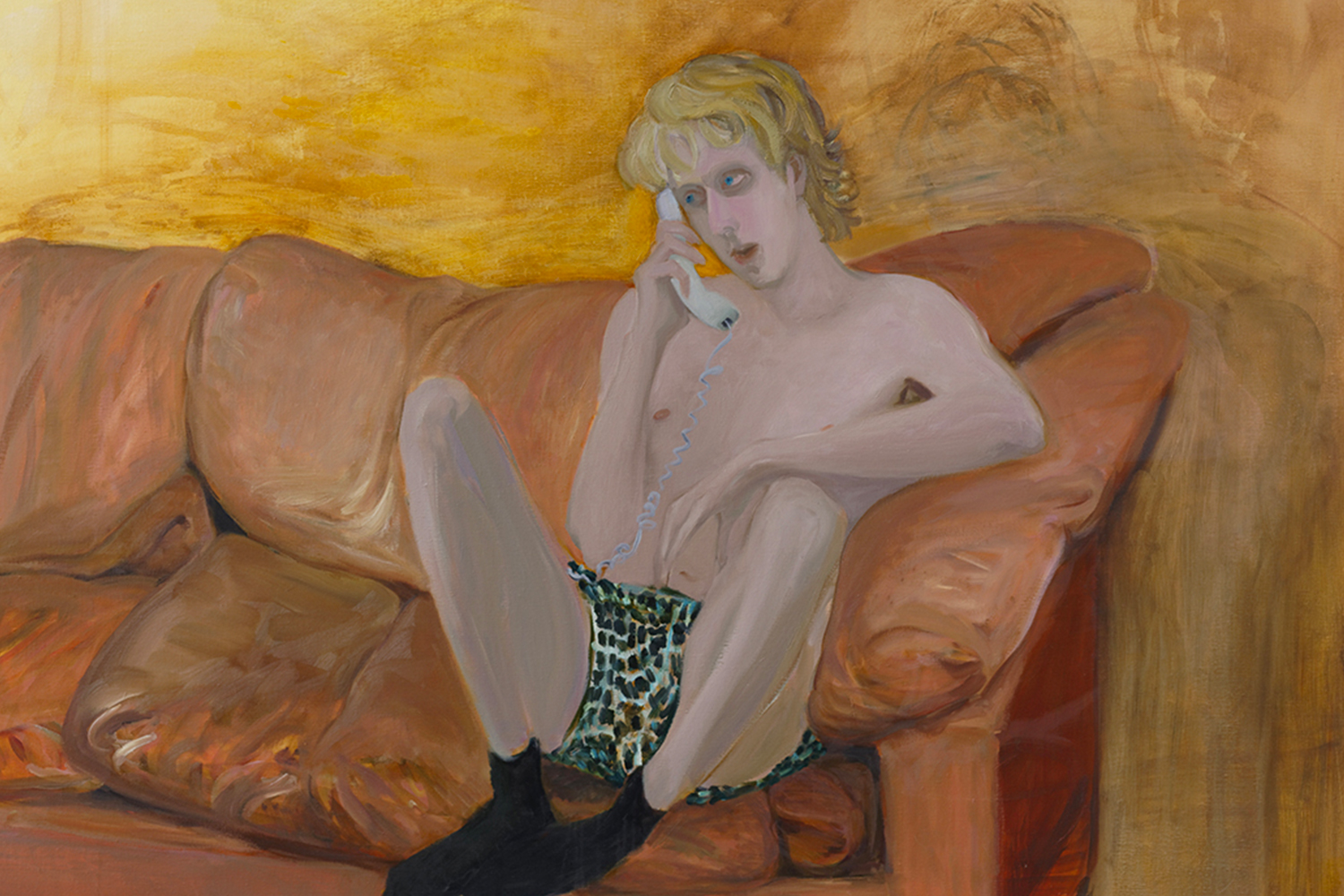

Gale zooms in on affective responses to fascism through real images as well. NOSEBLEED 13 is a sleek and velvety close-up of an ear. The blurry image, focused on the ear’s fleshly texture, takes on a fetishistic feeling. NOSEBLEED 12 is an uncomfortably enlarged screaming mouth. Both images have a sense of absence: the ear is devoid of its aural target, while the mouth is untethered from a speaking voice.

NOSEBLEED 10 borders on a purely anatomical study of an eye, stripped of all the images it can potentially capture, leaving only the iris in the frame. Disoriented and agitated, these images gesture toward how fascism feeds upon the unruly body’s instinctive drive for a collective sense of discipline.

For Gale, fascism is an actualizing fiction with its material basis in the dissipating real. Understanding the organizing principles of fascism requires the production of images that lurk near existent sites of trauma – in this case, the stadium and its concomitant history of spectacle. With a coolness that is appalling and seductive, Gale archives the theatrical and abject act of subjugating oneself to the collective, both spatially and socially. The work serves simultaneously as a cautionary tale and a docudrama.