The trench coat — a nearly universal item of clothing prized for both its fashion and functionality — was born in the middle of an epoch-defining disaster. Made of lightweight and water-resistant gabardine by Thomas Burberry and his eponymous fashion house, it served two purposes in World War I: to shield British troops from the deadly dampness and chill of trench warfare, and to indicate the status of the higher-ranking officers who were permitted to wear them with add-on adornments such as epaulettes or shoulder straps. When these soldiers returned home after the war, they kept their coats, and the coat gained popularity among Brits for both its form and utility. Exemplified by Burberry’s elegantly tailored version, the trench remained popular through the Second World War and into the 1950s, when it became a garment of choice for film noir antiheroes. In the last half of the twentieth century, though, it lost some of its military poise and polish. A looser leather version became a favorite of anti-establishment punks, and the coat’s ability to conceal gave it an air of criminality in pop culture – a common costume for flashers, dealers, and school shooters. This brings us to the present day, where the trench can be found both on the street and the runway. Far removed from their wartime origins, trenches and “military-style” items such as camouflage are hardly associated with their violent beginnings. They are civilians now.

Fashion’s warm embrace of military signifiers is a frequent motif in “A WAY OF LIFE,” Elaine Cameron-Weir’s first show for the Chelsea outpost of London’s Lisson Gallery. Known for her industrial and conceptually driven practice that made her a breakout star in 2022’s Venice Biennale, Cameron-Weir explores capitalism’s enduring fascination with the aesthetics of doomsday and disaster — from world wars to the Second Coming and all of the dystopian TV shows and novels in between — at a time when the end-times seem very near.

The aforementioned trench is the focal point of two interconnected sculptures in the gallery’s front room: pupil of couture / 4horsemen hairshirt (SS 2024 apocalypse collection) (2023) and western procession of oldest wounds (hit parade) wrecked high altar of buying tears (2024). Both are suspended from Lisson’s ceiling, creating a spectacle with an ominous sense of presence. The former uses stainless steel chains to suspend a gnarly, layered leather trench by its sleeves. The positioning of the coat and its implied, ghostly wearer is that of a crucifixion scene: a man — perhaps holy, perhaps not — hung by his uniform and left to rot in the sun. The installation’s other half hangs parallel and consists of a conveyor belt adorned with horseshoes. The belt is swathed across the room in an inexplicably delicate manner, its position held in place with destroyed barrel weights. The blown-out rims of the barrels suggest the religious motif of stigmata – another reminder of martyrdom and resurrection. Surrounding these sculptures, small pendants, all appropriately titled marginalia (2024) and each containing drawings of barbed wire, hang intermittently on the walls, recalling both a key facet of dystopian architecture and the biblical crown of thorns.

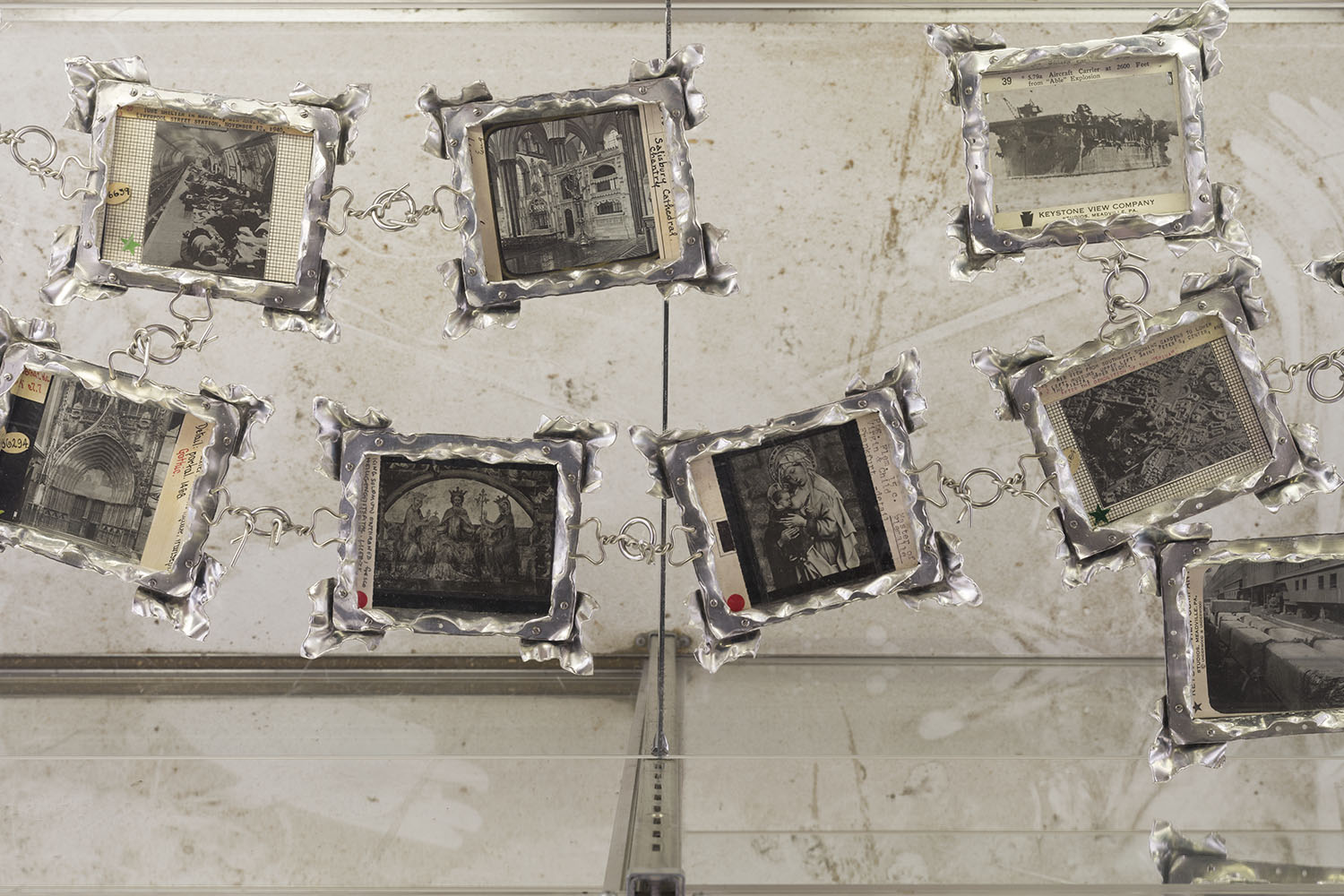

In the back room, Cameron-Weir creates more secular altars to the End. Three groups of paired sculptures are erected around the smaller gallery, recalling the showrooms of fashionable lords of darkness, such as Rick Owens and Hedi Slimane. The first two – MY LIFE MY WAY and MY WAY MY LIFE (both 2024) – are made of tarnished glass display cases straight out of a dirty pawn shop basement. Taken from the title, glowing neon signs of the phrases “MY WAY” and “MY LIFE” sit on the shelves, as if the very idea of selfhood is now for sale. Across the room, the pest of affectation — fleas have fleas and more than well dressed well badly dressed — and itchy to boot (both 2024) hang on the wall. The twin sculptures are made of the same materials: mirrored steel fire doors are covered in horseshoe nails and enamel fragments as a single leather trench is suspended over each mirror with a meat hook – a horrific image that recalls the brutality of butchery. From the mirrors, you can see the final works in “A WAY OF LIFE”: dance macabre / waste management and stage makeup / vanitas (both 2024), which sit discarded on the cold concrete floor. Steel casts of crumpled work jackets sit on rusted metal, their holiness implied by the lit tea candles that surround them. In these pieces, like all the sculptures included in this show, aesthetic qualities carry deep social meaning: the trappings of hypebeasts, punks, Jesus freaks, and soldiers become symbols for an imploding society – sly harbingers of disasters that feel more possible than ever. Cameron-Weir’s nightmarish “A WAY OF LIFE” portrays the intentions of our apocalyptic set dressing with terrifying clarity. This is a normalization process, one of ubiquity that softens the inevitable blow of doomsday.