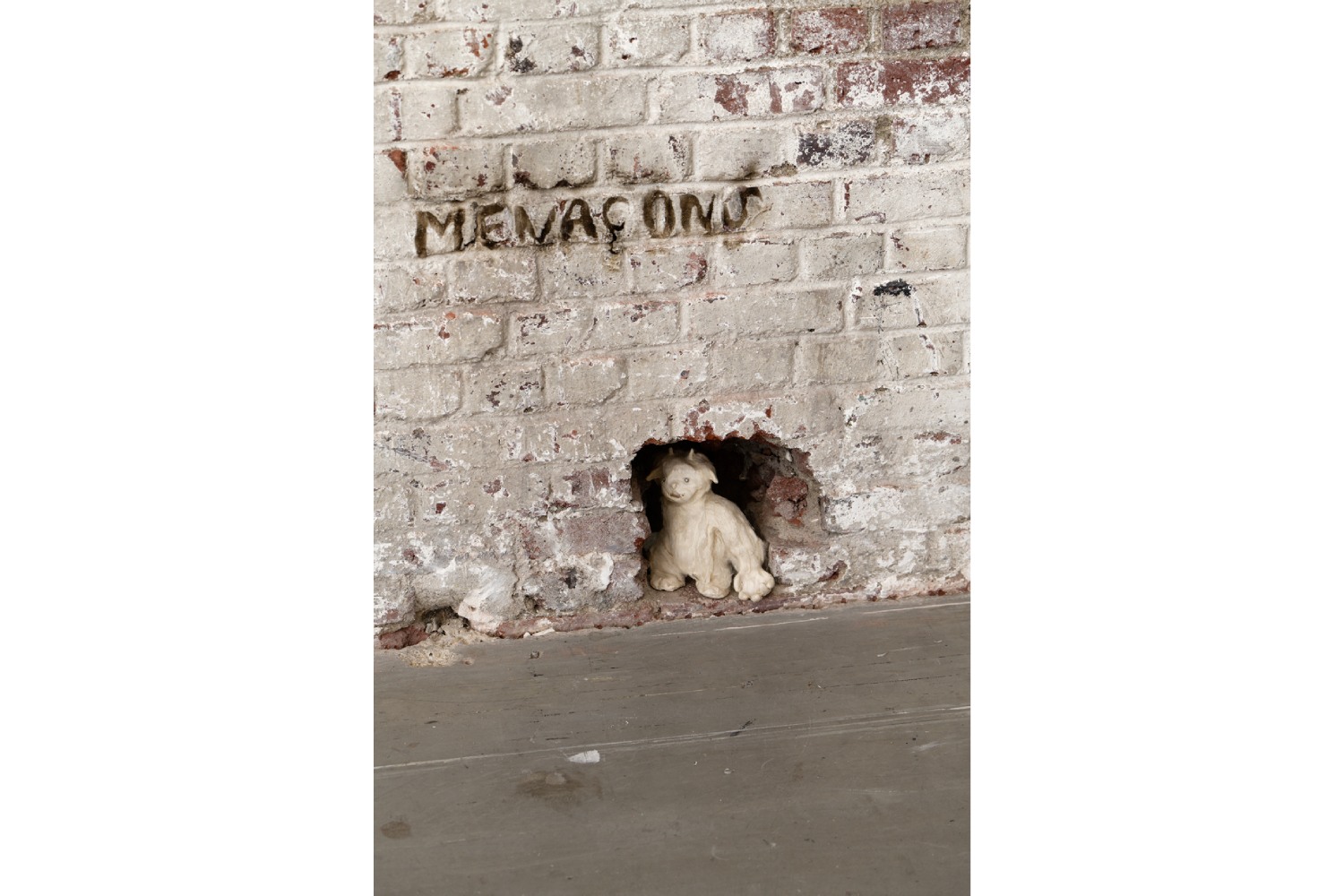

I wrote last year that Paris was blooming, offering a vast museum program whose sheer scale seemed to have been boosted by the arrival of Paris + by Art Basel. This year, we’re a long way from that extravaganza. The international climate is no longer one of happy reunions, the end of the health crisis and endless grandstanding. Although Paris is undoubtedly (re)gaining its status as Europe’s new artistic epicenter, Frieze, despite attracting fewer international visitors a week earlier, doubtless siphoned off some of the twentieth-anniversary excitement, craziness, and celebration. In the meantime, international and geopolitical concerns and their local transplantations lent a heaviness to the air, overshadowing the sense of lightness and festivity. This context did not prevent the festive opening of new Parisian spaces by international galleries such as Mendes Wood — which opened with an exhibition curated by Fernanda Brenner — Hauser & Wirth, Modern Art, and others, joining the vast cohort of previous openings. The geography of Parisian galleries has undergone a sea change, and its epicenter in the Marais has partially shifted to the 8th and 1st arrondissements. The Parisian galleries — Poggi with its new six-hundred-square-meter space opposite the Centre Pompidou in the Marais, and the second intimate spot that Galerie Mitterrand just opened in the 1st — are confirming this ongoing bipolarization. Meanwhile, alongside a rich program in the galleries — think the Mamma Andersson show (David Zwirner) and the comprehensive Chen Zhen survey (Continua) — alternative fairs such as the always super-exciting Paris Internationale, Asia Now, AKAA (Also Known as Africa), and the Design Miami debut meant more and more to see.

Paris + par Art Basel reaffirmed its high standards, notwithstanding a further trend toward the spectacular, which maybe drew the event closer to a Basel still scaled down pending its reopening — at last! — at the historic Grand Palais in October 2024. This edition offered more exhibition offshoots in Paris, in addition to last year’s venues and the Conversations program.

The “Fifth Season” tour of the Jardin des Tuileries–Domaine National du Louvre, curated by freshly appointed Louvre-Lens director Annabelle Ténèze, provided a delightfully sensual ramble in the form of twenty-five works structured around the concepts of ecosystem, interaction, and symbiosis with minerals, plants, water, and the garden’s inhabitants. Very much the opposite of a simple overlay, the three-dimensional works by John Giorno, General Idea, Meriem Bennani, Gaetano Pesce, Alex Ayed, Julien Berthier, Henrique Oliveira, Jean Prouvé & Jean-Michel Jeanneret, and quite a few others, most of them specially commissioned, probed the notion of art in the public space; the outcome was a subtle itinerary which in a way set the tone for a 2023 off-site program and exhibitions with an increased emphasis on restraint, via an exploration of collective and individual interiority that leaves room for society’s urgent issues.

In keeping with this image, the usual exhibitions in Paris, most of which are on view until January, are less spectacular and grandiloquent than last year, but also more museum-like, more profound, and more complex than demonstrative, which doesn’t exclude formal glamorization.

The Bourse de Commerce dominates the contemporary field this year with a series of exhibitions, all in-depth, focusing on America’s counterculture. Co-curated by Catherine Wood, in charge of the exhibition at the Tate (London), and Jean-Marie Gallais, curator at the Bourse de Commerce (Paris), Mike Kelley’s exhibition “Ghost and Spirit” offers a renewed reading of Kelley’s oeuvre, in some places constrained by space. The well-documented exhibition, along with its now emblematic “French glamour touch,” will move to the Tate in 2024 in a different form. In the Bourse de Commerce’s vast nave, Kelley’s installation Kandors Full Set (2005–09) appropriates and deconstructs the Superman myth — that metonym for the dominant American culture. In a totally darkened environment set under a purpose-built “bell-shaped” structure, each of the twenty-one sculptural iterations in colored urethane resin of the city of Kandor — home of the hero’s natal cosmogony — constitutes the reworking of one of its graphic representations. Never identical in the original comic strip, each iteration of the city, lit from within, is presented opposite its colored glass cloche and a set of sixteen very large Kandor bottles, symbols of its encapsulation. Its planetary home destroyed, the utopian city once located on Krypton has been miniaturized and encased by the superhero in order to be saved. By appropriating and reproducing these differences, which can be attributed to the comic book artists’ lack of interest in the hero’s birthplace, Kelley signifies the fragility of a hero who takes refuge in his “Fortress of Solitude” to contemplate the remnants of his past. The colorful monumentality of the installation, enhanced tenfold by this three-dimensional plunge into darkness, and by the projection on the wall of futuristic-sounding videos evoking an oppressive sci-fi universe (Kandor Bottles, 2007), immerse the visitor in the atmosphere of the utopian city, counteracting the trivial yet complex three-dimensional translations of its multiple graphic occurrences.

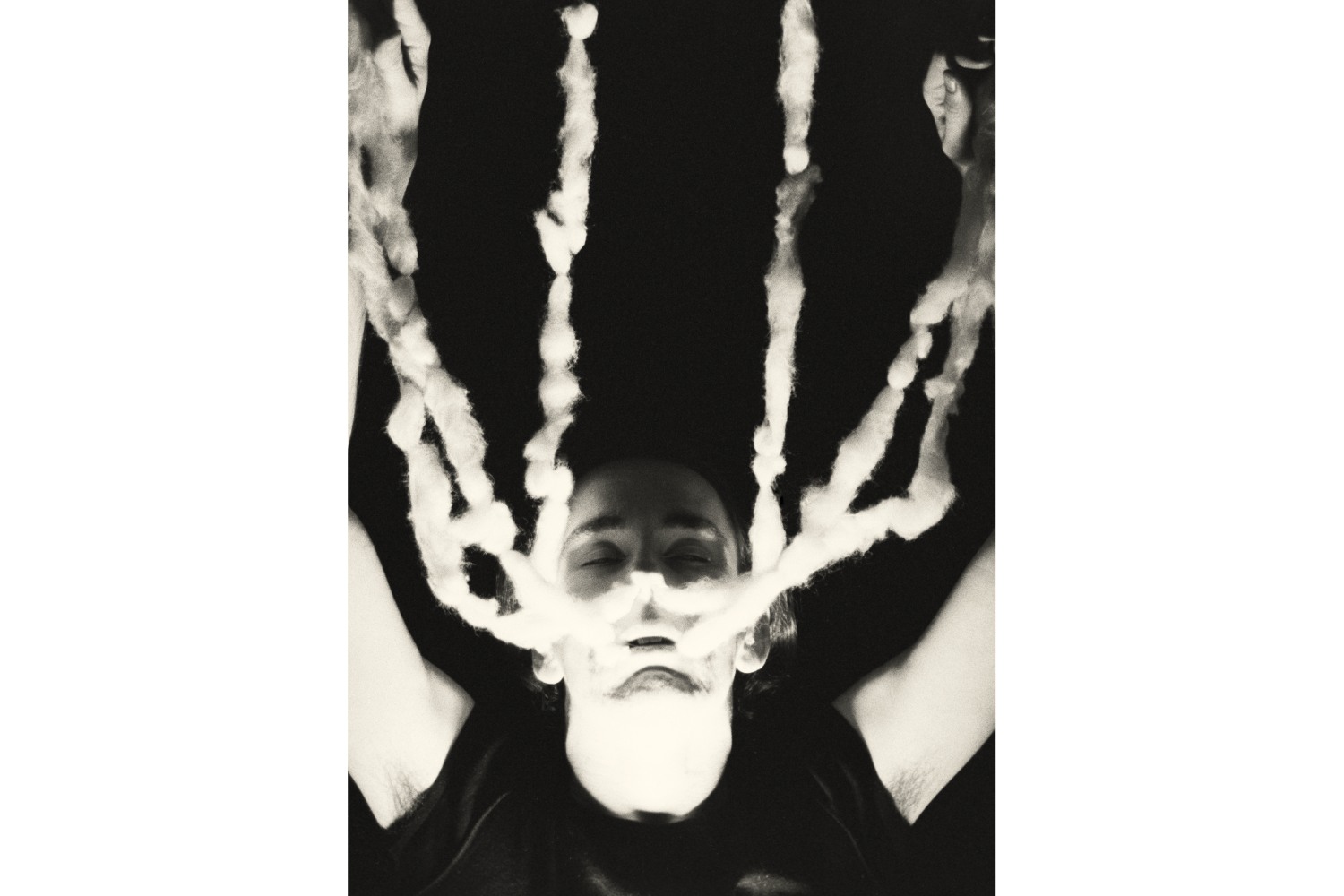

The following rooms provide a comprehensive overview of Kelley’s output, ranging from such extremely well-documented early works as the graduation piece Gothic Birdhouse (1978) — a minimalist assemblage of two conical forms, one of which has a cavity allowing a bird to enter — to the Perspectaphone (1977–1978), or his first video of a performative work, The Banana Man (1983), set next to his costume, which tweaks the eponymous character. Emblematic installations and works are set at the heart of the exhibition, among them Performance Related Objects (1988), a vast wooden platform featuring components that include “sculpture-objects” referring back to his performances of the 1970s and 1980s. Four of the iconic Ectoplasm Photographs (1978/2009), which show Kelley as if in ecstasy — eyes white, mouth open, ghostly forms seeming to escape from his nostrils like thick cigarette smoke, recalling spiritualist works and their Dada and Surrealist offshoots — are shown together with a set of photographs and archival elements, which document the works and have never been exhibited. The iconic minimalist ensemble Monkey Island (1982–83) has been gathered together again for the exhibition, as well as the arch-cultish maximalist installation Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstruction #27 (Gospel Rocket) (2004–05); reactivated, this work rounds off a journey that allows us to fully apprehend the complexity of Kelley’s work.

Curated by Caroline Bourgeois on the second floor of the Bourse de Commerce, Ser Serpas’s museum-style installation “I fear (J’ai peur)” dismantles the myth of painting via a series of unmounted canvases in different formats: suspended like pieces of fabric carelessly affixed to a metal curtain rod traversing the entire installation space, as if hung out to dry. Superimposed, they form a vast ensemble. Some of them are partially figurative, recalling earlier canvases inspired by details of the body; others are essentially abstract, in a vast, partially autobiographical whole which, as in Serpas’s other works, incudes experimental techniques that augment the pictorial material. Three-dimensional assemblages laid out on the floor echo this first ensemble: partially veiled with a thin, transparent white fabric, they allow us to grasp the form while blurring the details. Inspired by Alejandro Amenábar’s fantasy film The Others (2001), and more particularly by the voices of ghosts echoing through the rooms of the uninhabited house, its furniture and objects abandoned and slipcovered, the installation calls up childhood memories. Leyland Kirby, revisiting here his emblematic project The Caretaker, adds a powerful sound dimension, accentuating the cinematographic and performative aspect of the work, and augmenting the space with a fourth dimension.

On the other floors, smaller but equally museum-like exhibitions — the Lee Lozano show “Strike” presented in collaboration with the Pinacoteca Agnelli, Turin, and curated by Sarah Cosulich and Lucrezia Calabrò Visconti, together with Mira Schor’s “Moon Room” — are also well worth an attentive visit.

The glamorous French touch is also reflected in the Palais de Tokyo’s curating of a number of exhibitions, but this does not prevent the Paris art center from pursuing an ambitious policy based on ecological issues, permaculture, and care.

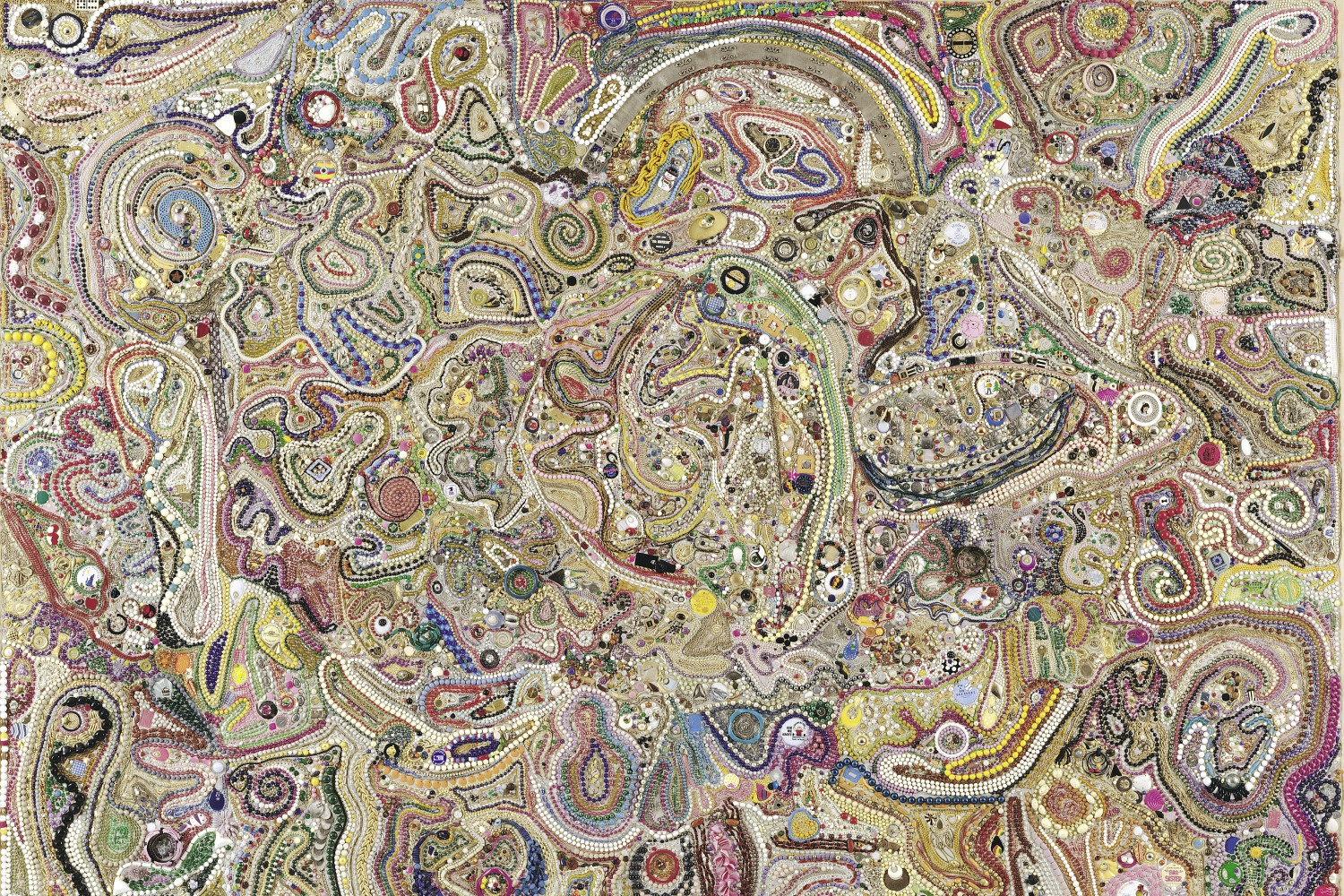

The baroque inventiveness of the Ashley Hans Scheirl and Jakob Lena Knebl exhibition “Doppelganger!”, curated by Daria de Beauvais, echoes the chromatic completeness of Mike Kelley’s Kandors Full Set installation at the Bourse de Commerce. It highlights the important and sometimes unjustly misunderstood work of these two avant-garde artists, who since the 1970s and 1980s have been exploring the transformation and plasticity of identity, the concept of queerness, and the transformation of gender, in both shared and personal works. Scheirl, who acquired the male identity of Hans before re-feminizing as Ashley Hans in 2016, has made a name for herself with her experimental and performative films anticipating the international queer and transgender scene. The duo represented Austria at the 59th Venice Biennale. This exhibition, structured around an interplay of colored mirrors, lights, and display cases that affirm the continuity of a multitude of contingent spaces in creating a single heterotopic space, interacts with the architectural complexity of the Palais de Tokyo’s basements and amplifies the extent and baroque folly of the work, while leaving enough space for less maximalist videos shown on small screens. These devices allow the work to be better explored and understood. The vast canvases in green and blue tones, some of which Ashley Hans Scheirl created site-specifically, resonate in counterpoint to these “spaces of desire” harking back to a 1970s and 1980s aesthetic marked by sexual liberation and significant social movements, with Jakob Lena Knebl’s three-dimensional works giving full rein to their excessiveness, and encouraging us to think of the exhibition “as a theatrical set inhabited and to be inhabited.” References to Hans Bellmer, who has a showcase installation dedicated to him, and to other avant-gardes — note the reference to Marcel Duchamp’s Fontaine (1917) in the form of an apple-green lacquered toilet bowl, turned upside down and placed on the floor against a wall, and the plausible reference to Tu m’ (1918) in the series of three large-format sprinklers that spring from vast painted volumes in the shape of vases — are omnipresent, as are references to the 1970s and 1980s. The sculptural three-dimensional forms, some of which, such as a pair of marble platform boots augmented with the kitschiest of dried feather-duster flowers, presented in a showcase, or an augmented golden palm tree and its sofa, which evoke wild nights at Castel and other iconic Parisian nightclubs of the period, are quasi-ready-mades based on objects collected from websites. Meanwhile others have been created in abstracto for the exhibition, as well as several videos, some of which come from the artists’ archives. Much more detail would be needed to do justice to this seemingly frantic, breathless, but in reality extremely controlled exhibition, which runs alongside four others at the Palais de Tokyo.

Lili Reynaud-Dewar’s exhibition “Hello, my name is Lili and we are many,” curated by François Piron, brings new life to the exhibition form by reactivating spatially the framework of lived experiences and filmed interviews. The deliberately literal recreation of a set of locations where these took place — hotel rooms, a restaurant — and where the visitor is invited to take a seat, pushes the system to its extreme in its repetition of the motif. The videos shot in these rooms, with their unchanging setup and immediately identifiable red hue, are formally similar to the ensemble shown at the Centre Pompidou in 2021 as part of the Prix Marcel Duchamp exhibition, of which Lili Raynaud-Dewar was the winner. In an exercise in self-identification, the videos are projected onto screens above the beds where visitors can lie down to contemplate them. Other videos, shown on vast screens on the walls of the Palais de Tokyo’s main exhibition spaces, depict Lilli Reynaud-Dewar dancing naked, her body coated in silver paint, in the empty spaces of the Palais de Tokyo and in Myriam Cahn’s earlier exhibition, in accordance with the artist’s recurring modus operandi.

Curated by Valentina D’Avenia and Clément Raveu, the subtle, fresh “Hors de la nuit des normes, hors de l’énorme ennui” is an exhibition “that interweaves works and archives, contemporary and historical fictions . . . poetry, sculpture, installation, drawing, painting and video, intruding spatially, blurring temporalities, transmitting and disseminating references, conjuring up deviant loves and more desirable futures.” The show deliberately follows on from the admirable “Exposé·es” shown a few months earlier. It brings together works by some twenty artists, including Cerith Wyn Evans, Ndayé Kouagou, Jimmy Beauquesne, Agnès Varda, and Rafael Moreno, after linking the youngest artists and the two curators in the exchange and residency space La Friche for the three months preceding the exhibition.

Ndayé Kouagou, who is showing a new video here, is also unveiling his first large-scale monographic exhibition at Le Plateau Frac Ile-de-France. Coming in the wake of the Fondation Louis Vuitton show, this one will give us a deeper understanding of his work, which goes far beyond the appearances of his emblematic videos and their glamorous “French” touch, which Kouagou subtly disseminates via the fashion background in which he made his start.

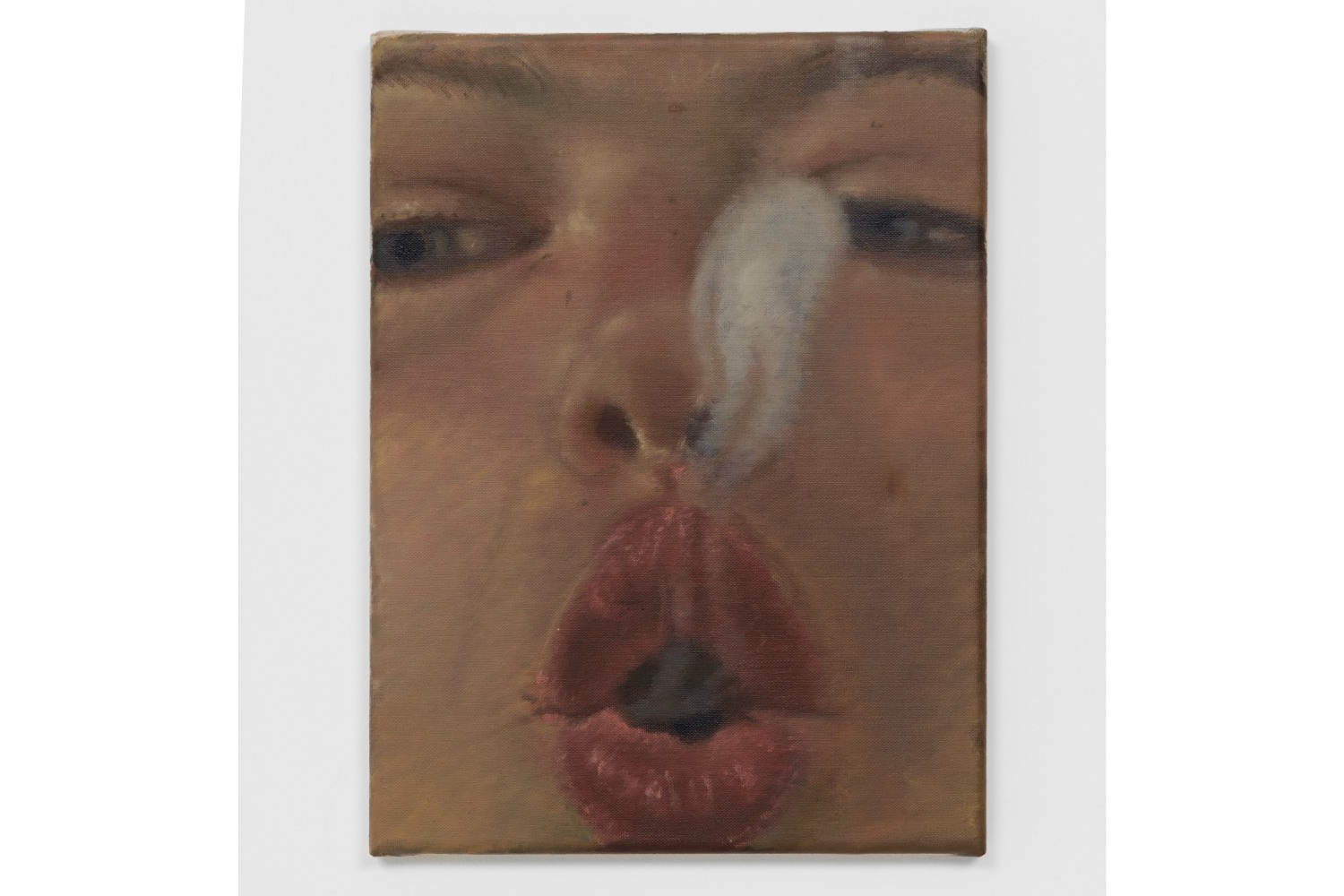

Now at Lafayette Anticipations, Issy Wood’s solo exhibition “Study for No,” curated by Rebecca Lamarche-Vadel, was previously reviewed in Flash Art. This is a major exhibition dealing with the intimate and the collective, deploying works all over the building, including on the floors. Structured around a set of anti-narcissistic self-portraits from which emerges a profound reflection on the very essence of pictorial representation, and a set of “still lifes” within a secretly (self)-narrative exhibition, it explores not only the flaws of society — and those of the artist — but also the objects of desire generated by a consumer society that Wood envisages as “toxic.”

The result of a residency at Lafayette Anticipations, Akeem Smith’s powerful exhibition “One Last Cry” resonates with the previous show in its critical reuse of waste materials from consumer society, and in the depth of the (self-)portraits generated. Sculptural assemblages of elements collected by the artist in Kingston, Philadelphia, and Paris, augmented by elements from his own archives, and the pedestals he has constructed for them from recycled wood, make up a set of three-dimensional works laid out on the floor that form unspoken historicized self-portraits. They powerfully echo the installation Dovecote (2020), which encapsulates in the scrolls of an ornamental white wrought-iron gate a vast video screen showing a work resulting from a montage of elements contained in Jamaican dancehall sequences from the 1980s to 2000 that are part of the artist’s collection. Built around excerpts showing close-up portraits of women staring into the camera, and music composed of sound elements taken from documentation of Jamaican funerals in Smith’s archives, the work elicits a sense of meditative depth and hypnotic force.

At the Fondation Louis Vuitton, the sumptuous Rothko exhibition, the most extensive ever devoted to the artist, is co-curated by historic curator Suzanne Pagé, who has directed the Fondation since its inception, and the artist’s son. Through its chronological scope and the recreation of ensembles, such as the reds and browns of the Seagram murals (1958–59) conserved at the Tate, the ochres and reds from the Rothko room in the Duncan Phillips collection (1953–57), and the somber Black and Grey ensemble (1969–70) originally destined for UNESCO, it exhales a sense of the artist’s ongoing inner experience of tragedy. Organized by rooms, the serial repetition and sumptuous accumulation encourage an almost meditative approach. It also allows us to follow the stages in the development of the work, from the figurative paintings of the 1930s and the little-known neo-surrealist works — think the magnificent Slow Swirl at the Edge of the Sea (1944), which immediately preceded the transition to abstraction — to what Rothko called his “experiments,” from the first so-called “multiform” abstract works of 1945–49 until the last.

To apprehend and contemplate the transition to abstraction with Untitled (1948), and the emergence in 1948/49 of the oeuvre’s systemic and systematic character, to apprehend the transitions from polyformism to the creation of depth via superimposition into strata of vast flat areas, is pure joy, even for ultra-contemporanists. As is contemplation of the works from the 1960s in Room 9, whose motif and punctuation vary slightly from the others, and which continue to experiment with painterly materiality and canvas.

Alex Ayed’s exhibition “Farewell” (Open Space #12), curated by Claudia Buizza and Ludovic Delalande — also co-curators of the Rothko exhibition — on the top floor of the Fondation Vuitton, revolves around an antenna-sculpture designed to translate the signals from the three-year sailing expedition the artist undertook for this project. Other sculptural elements are also designed to maintain this link in the form of a daily diary. In the basement, a pictorial installation by Chinese artist Xi-Lei also develops a meditative depth.

But we might also find ourselves wondering about the great return to modernism, in forms and formats not seen so systematically for a long time.

At the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris (MAM), the Nicolas de Staël exhibition stands alongside the work of Dana Schutz, curated by Anaël Pigeat, and Wade Guyton’s sumptuous Five Paintings (2013–15).

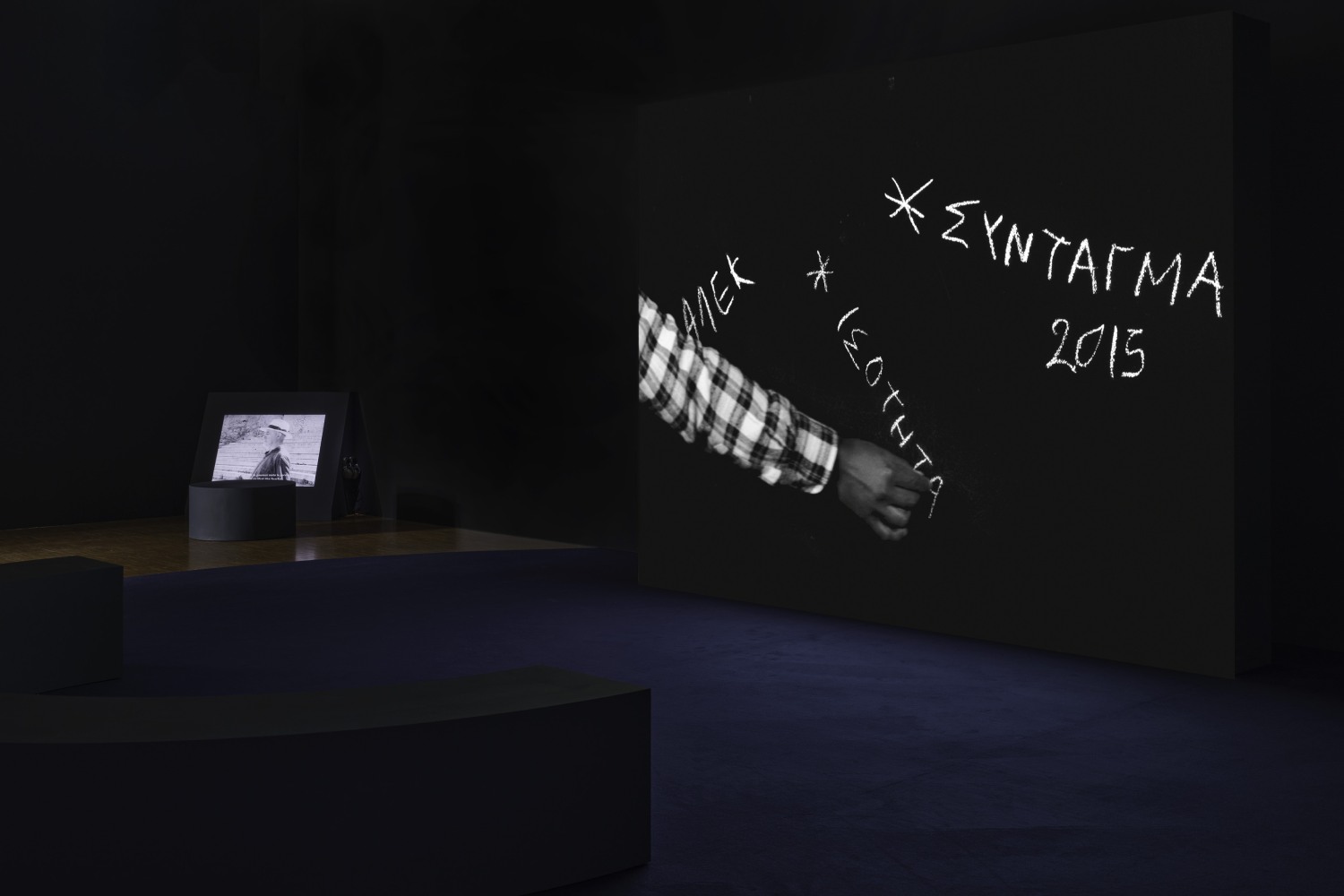

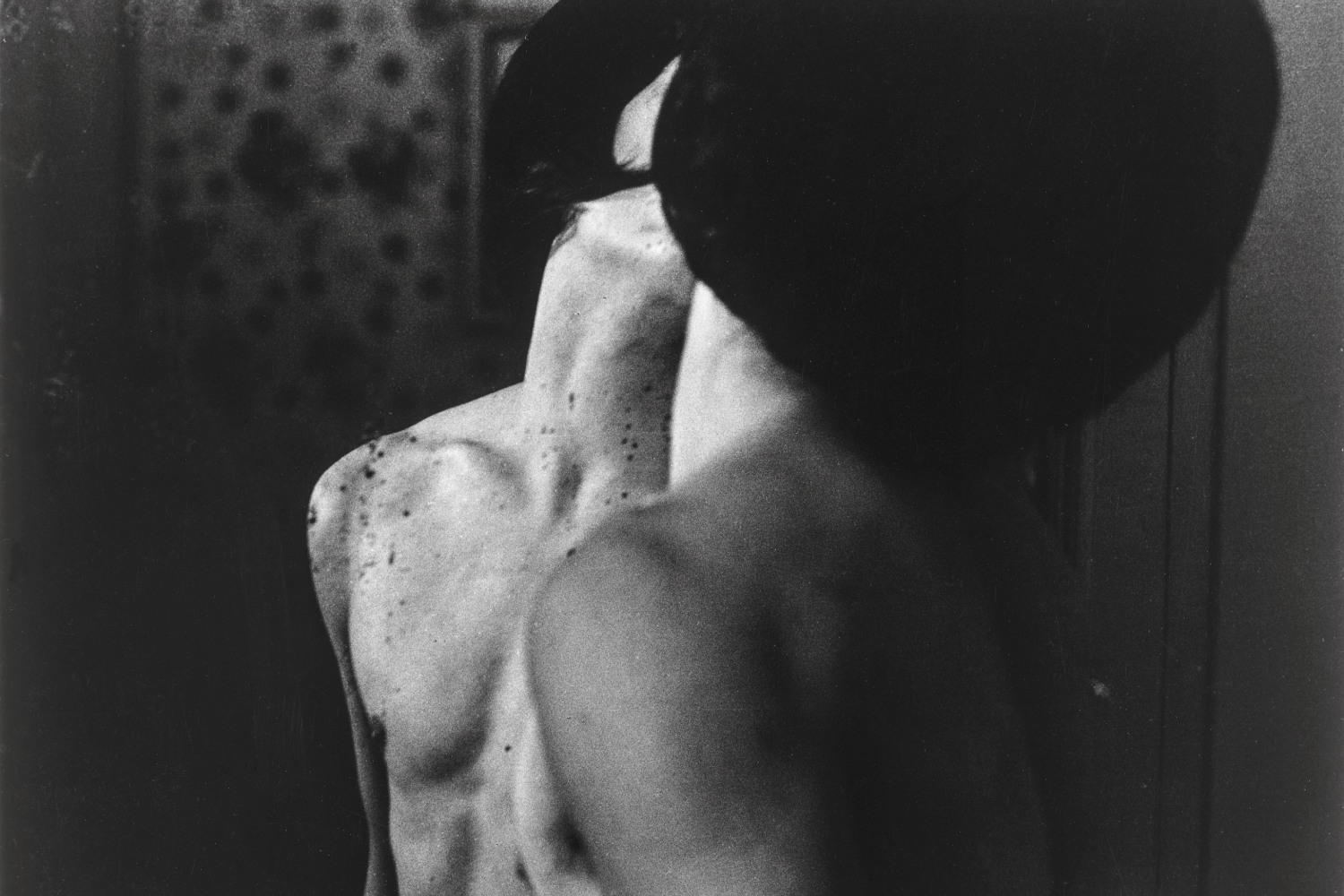

At the Centre Pompidou the encyclopedic exhibition “Corps à corps. Histoire de la Photographie,” a vast face-to-face encounter between the Museum’s photography holdings and the Marin Karmitz collection, is organized around classical photography, although a number of works fall outside this framework. The remarkably abundant exhibition “Picasso. Dessiner à l’infini” and the brief “Chagall at Work” look like a return to the Pompidou’s roots, while on the half-floor “Animal Politique,” a huge exhibition of paintings by Gilles Aillaud, unfolds in the galleries. The Prix Marcel Duchamp 2023 exhibition, which has been moved to the 4th floor and includes works by Bertille Bak, Bouchra Khalili, Massinissa Selmani, and Tarik Kiswanson, was also kept at a distance from the most ultra-contemporary forms, apart from the important work by laureate Tarik Kiswanson, which will be the subject of an extensive essay in the next issue of Flash Art.

At the other end of the spectrum, the exhibition at the Béton Salon art and research space, “Un-tuning together, pratiquer l’écoute avec Pauline Oliveros” comes up with new, activatable forms for spatial installations, designed by artist Konstantinos Kyriakopoulos and curators Maud Jacquin and Émilie Renard to accompany the spatial deployment of performative works articulated around the “deep listening” work of the American sound artist and composer Pauline Oliveros.

The Prix de la Fondation Ricard 2023 exhibition, which this year featured a return to less formal works, made a number of artistic discoveries and was also curated by Fernanda Brenner.

As in 2022, artist run-spaces such as Artagon, alternative fairs such as Salon de Montrouge (curated by Work Method’s Guillaume Désanges and Coline Davenne), and Les Magasins Généraux (Pantin), which presented the exhibition Après l’Eclipse (After the Eclipse), presented a consistently exciting program of up-and-coming young artists, while also confirming the omnipresent return to the painting-form.

At the Chapelle des Beaux-Arts, artist Jessica Warboys, commissioned by Paris +, treats this return with absolute detachment, creating a collage of canvases presented on the floor according to a recurring protocol of coating the canvases with beeswax before immersing them in a body of water and immediately sprinkling mineral pigments on the ground of the banks. Accompanied by a video triptych, “This Tail Grows Among Ruins,” the exhibition comes full circle with the notion of symbiosis with nature that had been explored in the Jardin des Tuileries “Parcours” –– but this time in video and painterly form.

This double variation on the theme of reflection on form-painting and form-sculpture within the Paris + off-site public program is structured around the paradigm of anti-painting and anti-sculpture, which was further explored at the Palais d’Iéna by the ambitious and spectacular exhibition devoted to Buren and Pistoletto, each of whom produced a new body of work constituting one of the highlights of this Paris + program.