Having been awarded the Camden Art Centre’s 2022 Emerging Artist Prize at Frieze, Marina Xenofontos now presents “Public Domain,” her first institutional solo show in the United Kingdom.

All the works on display were crafted by the artist in 2023 specifically for the exhibition. Each piece dialogues with the museum’s architecture, blending into the space as minimal elements and remarks written on the margins of the artist’s personal experience and everyday life in public, urban, and domestic environments. Xenofontos’s artworks resonate with shared memory, intertwining remembrance, familiarity, and indecipherable nostalgia, and acting as diaphragms that oscillate between the private and the collective.

Main Engine opens the exhibition, introducing the formal and narrative direction and post-production process that guided the artist. The installation, as the artist explained to me, is made from a found industrial air conditioner that belonged to an asthma hospital on the island of Cyprus, where Marina was born and grew up. The piece activates intermittently, and its mechanism intersects with half of a wooden MDF (medium-density fiberboard) sphere on one side. Installed on the wall at the entrance of Camden’s exhibition rooms, the work can go almost unnoticed, merging with the rest of the space as an air circulation device.

The MDF sphere, in stark contrast with the industrial hardness of the spout, is not accidental. For those who have followed Marina’s path for some time, there is a familiar pattern and visual consistency, a recurrent character in the artist’s work also seen in the installation Twice Upon a While (2021). In that work, the figure of a tapered wooden avatar sat at a mirrored table, leaning on its image. As a wooden hermaphrodite embodying the myth of Narcissus, in Xenofontos’s universe the figure represented a videogame character destined to fail its game tasks continually. At Camden, a fragment — or better, a wreck — of this personage reappears.

There is a sense of elusiveness and the conjuring of something remote when encountering Class Memorial, a sculptural piece installed as a doorway between the entrance hall and Gallery 3. It’s a found door imported from Cyprus, functioning somewhere between a piece of architectural camouflage and a “stolen” urban pattern that anyone familiar with southern Europe will have seen hundreds of times. It is a light aluminum door with silver and gold bars, of the type mostly employed in standard housing. How might we better describe it? Finding a definition, let alone one suitable for Google Images, is difficult. And yet, here it is on display, straight from the archetype hard drive in the back of my mind –– and from our unspoken collective memory.

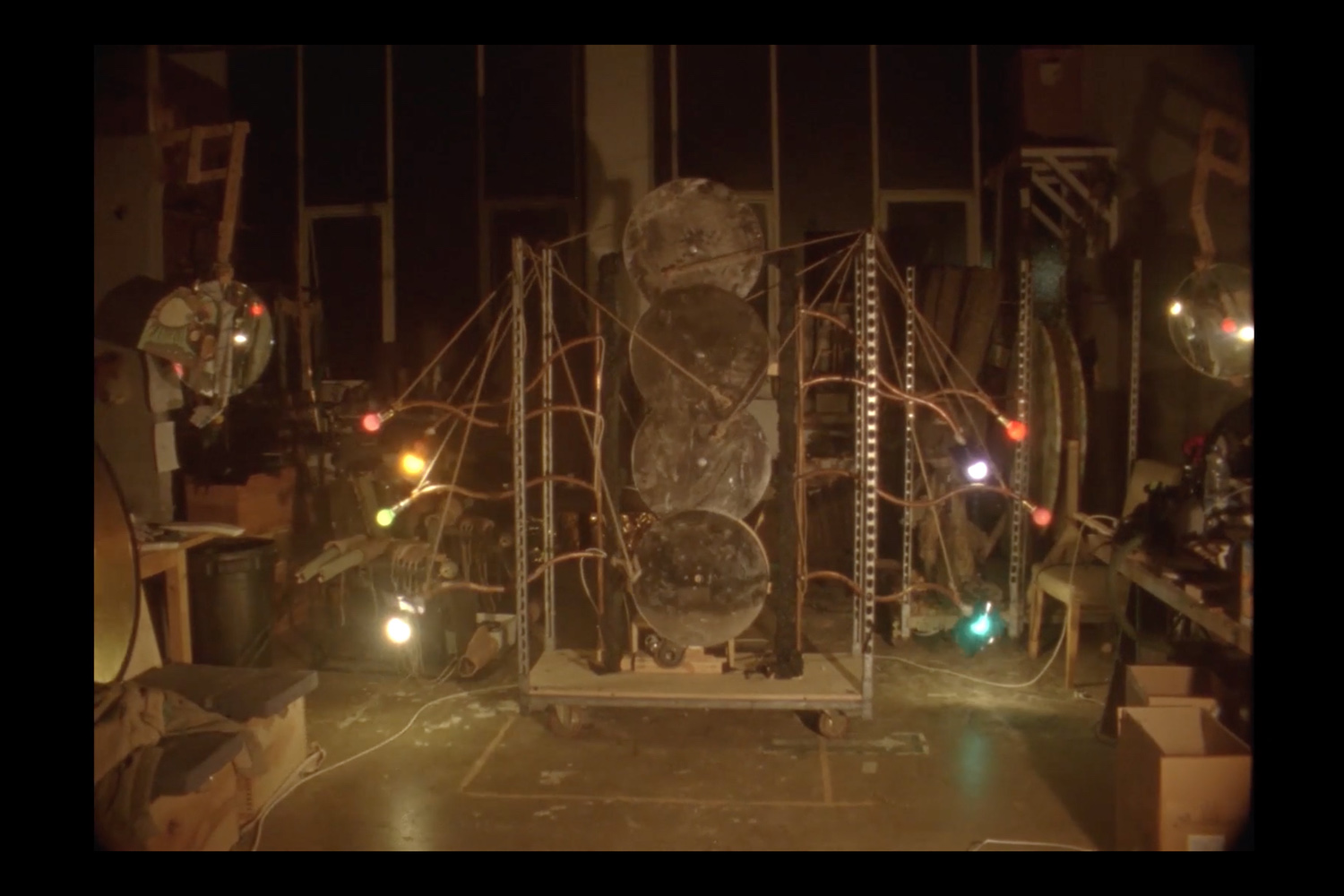

Past Class Memorial into Gallery 3, King, oh King, with your 12 swords! What work do you have for us today? Laziness, the King demands, and the children all reply, Let’s get to work! continues along the lines of this narrative. The two pieces of sculpture take up the matrix of a walking stick that belonged to Marina’s grandfather, here repeated several times to compose a modular structure made of silver-plated bronze castings suspended from the ceiling, almost touching the floor. A motor-driven system, powered by an electrical socket in another part of the same room, propels the sculptural filaments in a hypnotic interplay of mutual brushing, repeatedly frustrated by their lack of contact.

Not far away is The Queen, a two-part installation made of three plastic chairs of the classic monobloc type (the “Queen” model). Two of the chairs are stacked one on top of the other, and one is situated elsewhere in the space. Their backstory originates from the compulsory production accident that occurs every time the industrial chain transitions from one color to the next. The seats are thus the result of a production overrun due to a flaw in the machine, a mistake that alters the colors of these discarded specimens into a marble-like blend of white and cream –– reminiscent, among other things, of tones associated with MDF. It is a necessary mistake, one built into the product’s profitability and production cost.

The trait d’union that sums up the exhibition is a circular cross-referencing between movement and stasis –– fragments between the coming and going of viewers, people, and things. The thread is the overlapping of personal and collective social events inscribed as an invisible legacy on an object’s surface, marking the passage of a story in the form of a liquid reflection made in the absence of History. Found objects, removed, or displaced.

“Displaced” might apply to a generation that grew up without a firm idea of belonging, home, or provenance –– let alone destination. Rather than a generational condition formed out of stable geographies and history, it is a narrative entrusted to the continuous movements and flows of people and communities, which has characterized the web of stories propagated across the Mediterranean, both as a place and a cultural framework. The mimetic quality of Marina Xenofontos’s work is not so much, or not solely, one of a formal nature, as it is in an uncertain threshold between the functional, the found, and the displaced. Rather, it has more of a life-like quality, for it remains undetected and interiorized, registering no breaches between a collective narration and a personal account.

The Queen, The King, and Class Memorial are outcomes of an endeavor rooted in recovery and memory bricolage. Marina Xenofontos’s works have the delicate ability to move viewers with a snapshot of a time never lived and a sense of the loss of something never held –– specific perhaps to a generation to which nothing ever belonged. Marina’s work is one of the most interesting current examples of a generational reflection around the outcomes of a post-global world, experienced from southern Europe but recast in the great centers of the Western world: Amsterdam, New York, and London.

To see Marina again, we will wait for her next exhibition at the Kunstverein in Hamburg in 2024.