Over the last few years, the legacy of artist Hudinilson Jr. has undergone a significant transformation in his native Brazil, beginning with the long overdue retrospective “Explícito” at the Pinacoteca de São Paulo’s Estação. Curated by Ana Maria Maia and organized around a significant group of works gifted by the family in 2019, the expansive show was instrumental in cementing this elusive figure (who passed in 2013 after largely withdrawing from the mainstream) as one of the most important and formally intrepid artists of his generation. ICA Miami’s “Tension Zone” is poised to continue this important work, mounting the artist’s first museum showing within the US –– albeit on a much more modest scale.

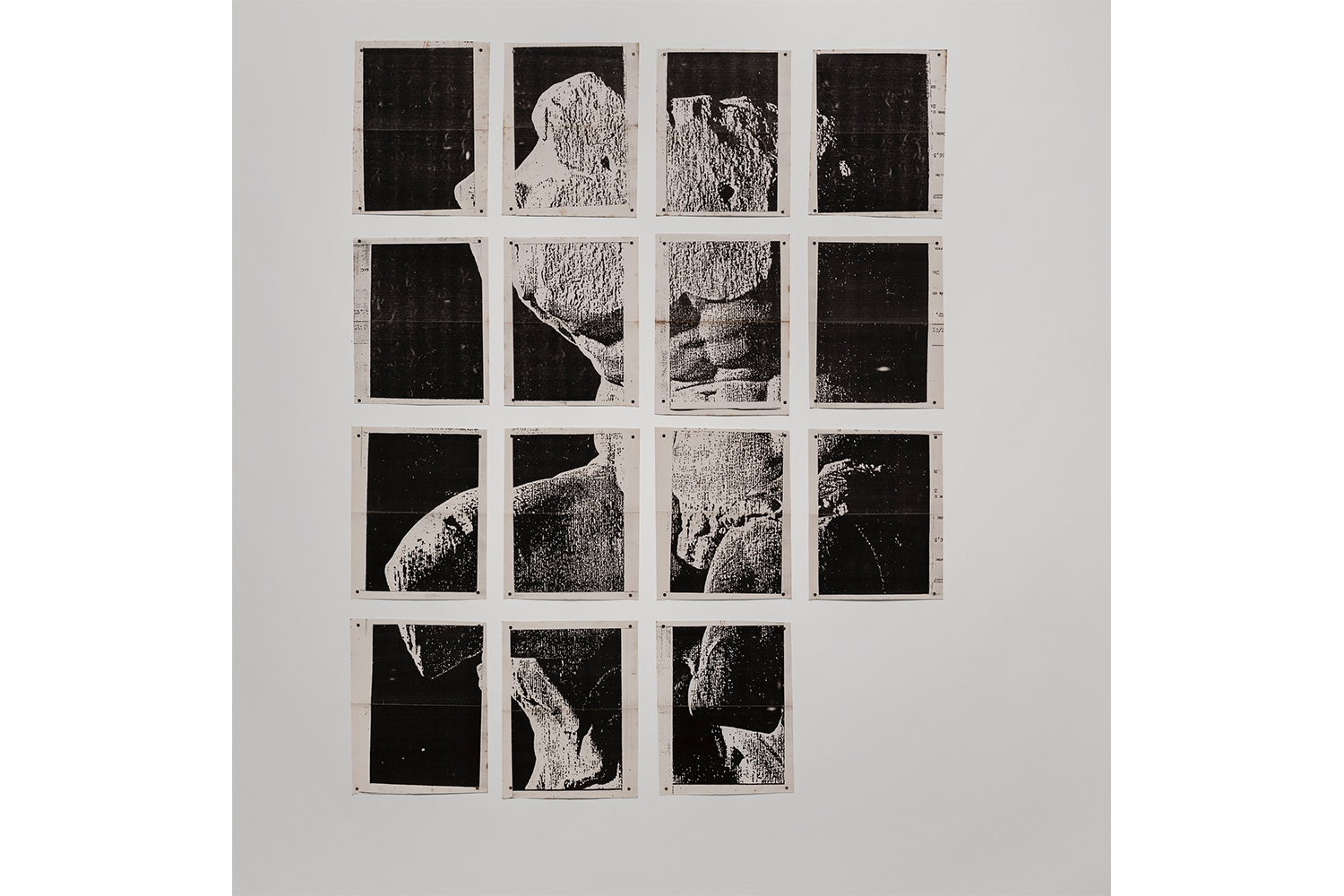

Occupying two of the ground-floor galleries, the exhibition proves effective because of its concise footprint, offering an introductory mini survey to a general audience that may not have previously encountered this rich and deeply emotive practice (this writer included). It is perhaps for this very reason that the curation tactfully dispenses with the typical chronological progression, opting instead for a more intuitive clustering of works across various periods, media, and modes of making. The majority of these groupings are articulated around Hudinilson Jr.’s pioneering xerographic works, which marked a pivotal turning point for the artist’s practice in the late 1970s, bridging the gap between social action/performance/activist intervention and discreet objects. The earliest works on view here date to the early 1980s, such as Untitled (1982), a collage assembled from various photocopies of the artist’s body pressed directly upon the scanning bed. The resulting images blur the line between index and gesture, fluttering in and out of legibility –– a nose glimpsed here, some fingers there, clusters of hair fading into abstraction.

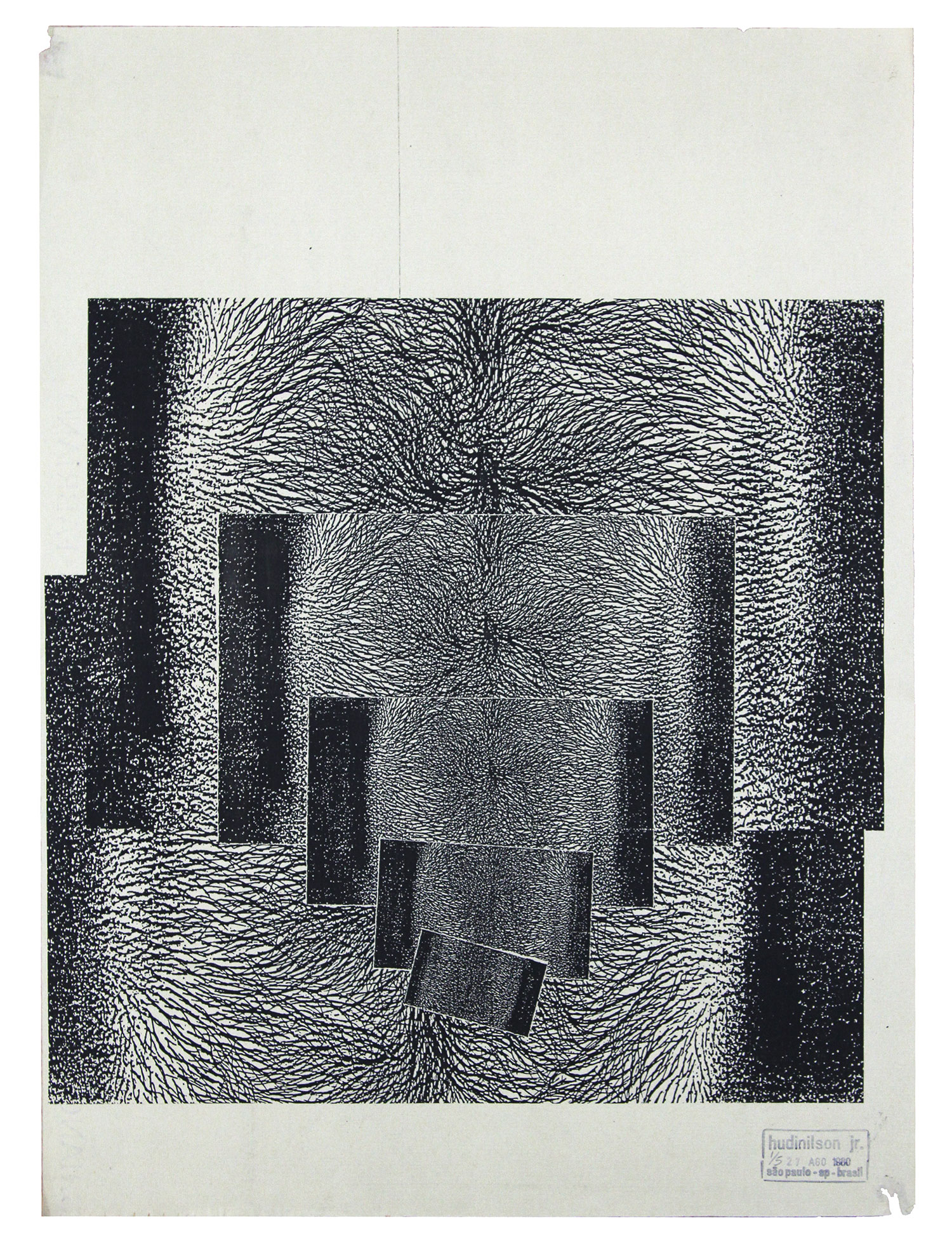

It is worth noting that this technique was developed during an experimental Xerox workshop the artist launched in 1975 at the aforementioned Pinacoteca, and which he continued to lead for the following six years. It was an act of double infiltration in line with previous public actions and gestures of detournement as realized with the artist collective/ activist group, 3NÓS3. Here, he managed to penetrate the inner sanctum, the institutional bureaucracy — which at the time was exceptionally rigid, shaped by the country’s staunchly conservative dictatorial regime — and gain access to a technology that was still largely inaccessible to a general public. This immediacy allowed Hudinilson Jr. to establish an unprecedented intimacy between the technology, his body, and those things it desired. It was a radical convergence, made more so by a repressive political climate that relegated all non-normative bodies and sexualities to the margins or the underground. This context illuminates the “Zona de Tensão” works, which lend the exhibition its title. In these, Hudinilson Jr. uses as his source material popular advertising images as well as gay pornographic magazines. These are handled with abandon: enlarged, cropped, re-copied until they emerge as bold reconfigurations of anonymous bodies that nevertheless assert their unique materiality and resonate with ghostly traces of unspoken desires made public.

This highly idiosyncratic and personal language has lost little of its currency. And it is one of the great contributions of this show that it historicizes it within an international scope; a Robert Gober permanent installation trickles away in the floor of one of the galleries, an unspoken touchstone and peer, but we can also note Richard Hawkins and Felipe Baeza as operating unbeknownst within his lineage. Just as important is the exhibition’s emphasis on the polymorphous nature of Hudinilson Jr.’s practice. Displayed alongside the Xerox works are Jean Cocteau-like drawings from the 1970s; mesmerizing and enigmatic paintings (“Amantes e casos”), whose mannerist flair feels impossibly contemporary; and dioramas in wooden boxes, oracular niches teeming with obfuscated meaning.

Perhaps at the core of this are the “Cadernos de Referência,” an ongoing project that the artist continued until his passing in 2013. These notebooks are built up with references, magazine cutouts, bits of newspaper, documents, and scribbles. They exist less as resolved artworks and more as an open-ended archive of ideas, potential gestures, and possible visual cues for further elaboration. They afford a glimpse into a rich, informal and messy cosmology — pulsatile and active even when viewed through the polite encasing of vintrine displays.