Across the top floor of Museion, the contemporary art institution in the Tyrolean town of Bolzano, booms the ghostly echo of “Ain’t Nobody,” the Chaka Khan song. The music is looped as part of Bojan Šarčević’s work Sentimentality is the Core (2018), which consists of a large, sarcophagus-like freezer. Slowly, over the course of the exhibition, the empty freezer fills with ice, crystal by crystal. The ’80s pop song, to Šarčević, represents late communist Yugoslavia, when neoliberal consumerism was just peeking around the corner. But at the same time, the frozen landscape and the reverberating chorus convey a profound loneliness. Ain’t nobody: this is all that remains audible in the echoing halls.

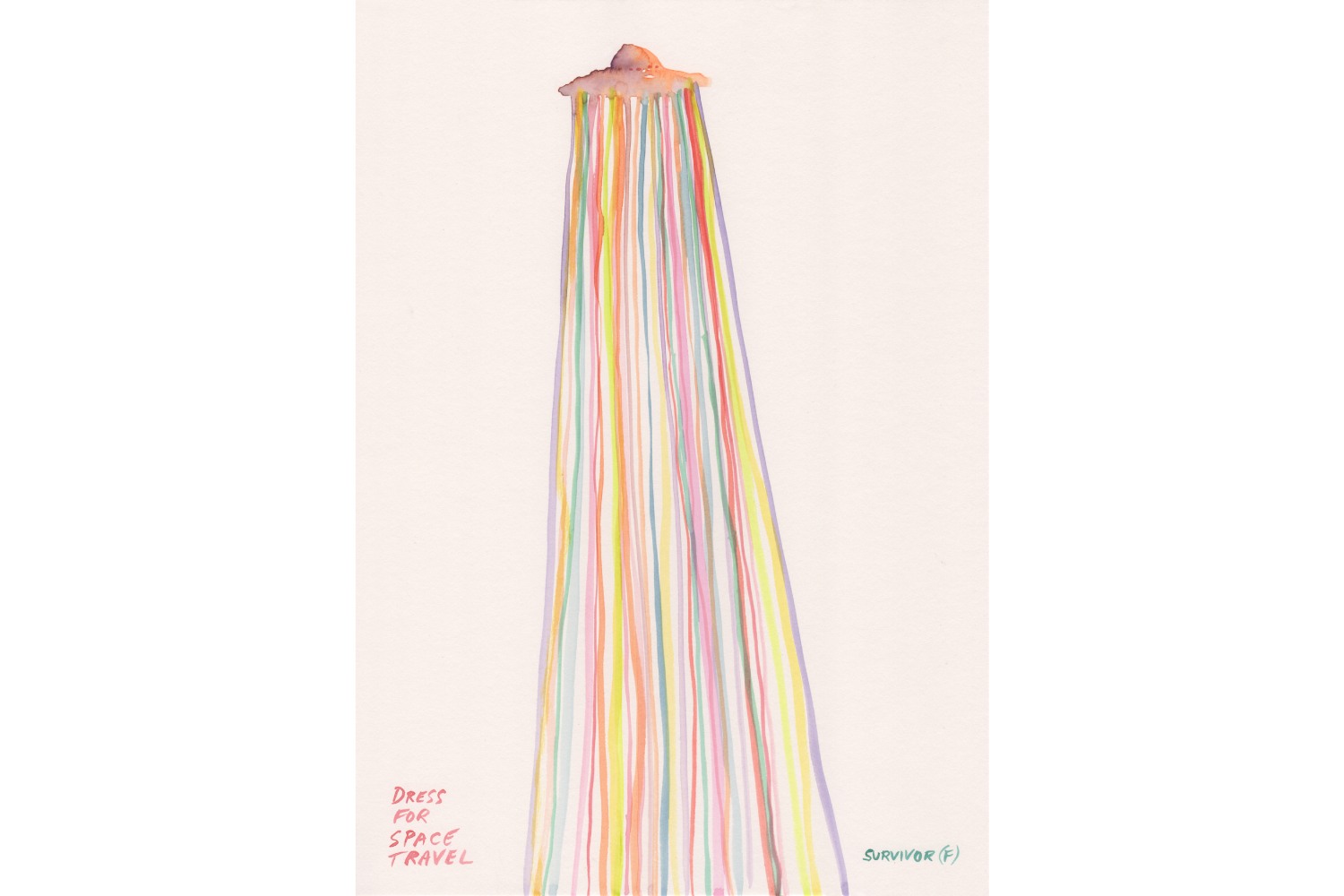

The exhibition “HOPE” is the third and final instalment of the “TECHNO HUMANITIES” series that began in 2021 with “TECHNO” and was continued the following year with “ Kingdom of the Ill.” The series attempts to strip techno to its basic tenets, and to understand it not merely as a subculture but as a cultural paradigm that touches on work and exhaustion, health and sickness. The third show tackles the way hope manifests when linear concepts of the future break down, when fragmentation and disorientation ensue. With very few exceptions, “HOPE” focuses on works from the past few years.

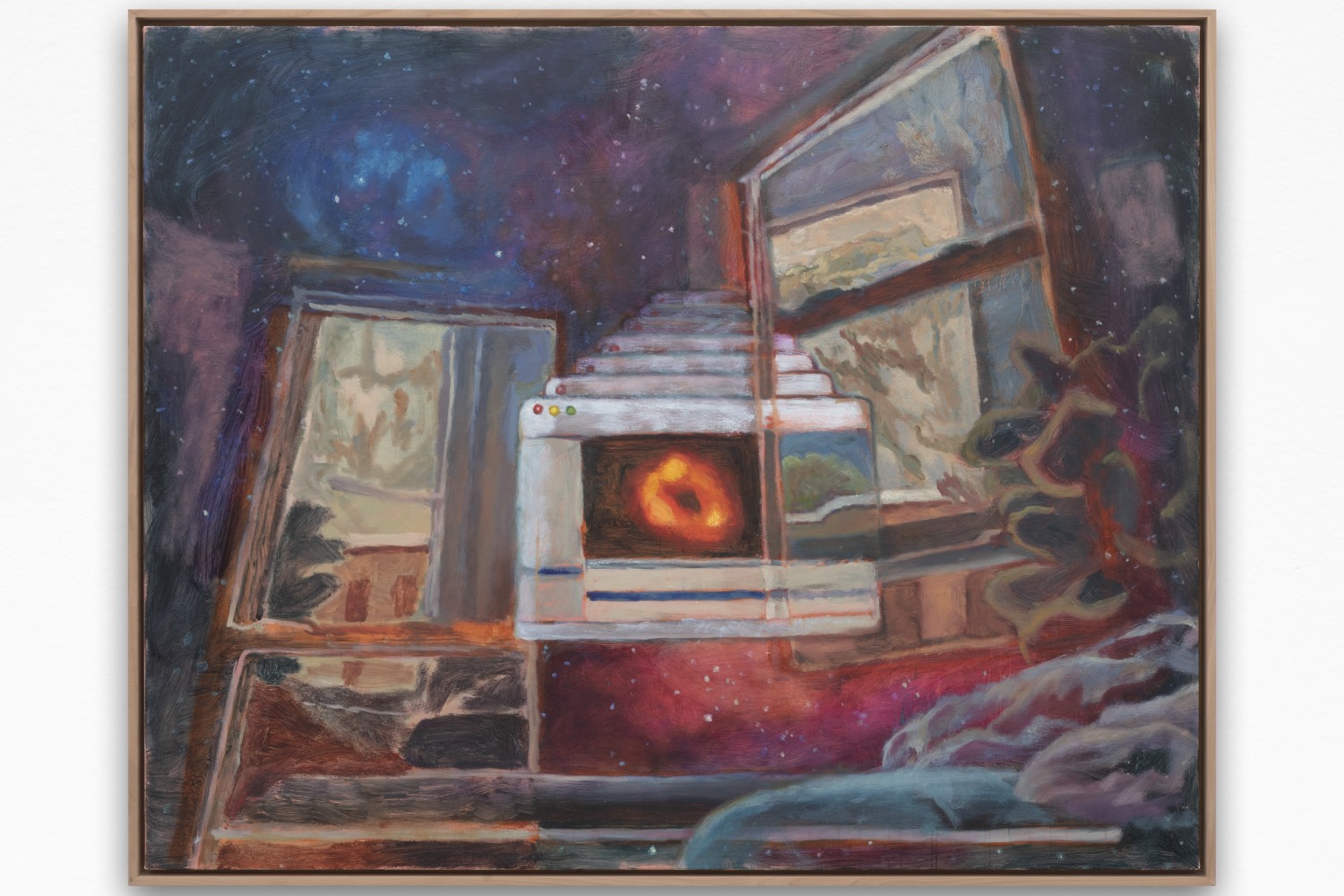

The exhibition — curated by Leonie Radine, Bart van der Heide, and musician and writer DeForrest Brown Jr. — suggests a parcourse from the top down. The spaces allude to video games and mythical pastoral paradises, and they allow visitors to drift between liminal states. The Sinofuturist video works of Lawrence Lek and LuYang blend into one another; Lek’s speaks of an island that promises healing through forgetfulness, and he presents CGI-generated depictions of the ruins of the Summer Palace in Beijing, which was looted by the British during the Opium War in 1860, as well as exhibition architectures of past centuries. Sites of collecting and cultural memory become places of oblivion in the Nepenthe Zone (2022–ongoing), named after the potion of forgetting in Greek mythology.

Lek’s vaporwave-adjacent, vibey landscapes are complemented by the garish colors of LuYang’s five-channel video. With its harsh imagery, like trading cards come to life in front of church pews, the piece draws from Buddhist and Hindu teachings on the connectedness of body and mind. Is hope a Nirvana-like state in the long-drawn-out tail end of post-internet art? Or is it found in Shu Lea Chang’s cyberpunk fantasy of a red pill that administers orgasms to whoever takes them? Certainly, Tony Cokes’s cerebral video work next door, set to a somber soundtrack by, among others, Burial, does not offer hope. It collages parts of a talk by Kodwo Eshun, in which he commemorates Mark Fisher, theorist of a future devoured by the forces of zombified neoliberalism.

“Thinking means venturing beyond,” wrote the ever-Hegelian philosopher Ernst Bloch in his Principle of Hope. But “HOPE” the exhibition is close to another tradition of thought, one that comprises many authors and many expressions. Kodwo Eshun has synthesized this in his book More Brilliant than the Sun, which derives a sonic futurism from jazz, funk, dub, and techno, all the genres that have been inscribed into the Afrodiasporic network of the Black Atlantic — “a rhizomorphic, fractal structure,” in the words of sociologist Paul Gilroy.

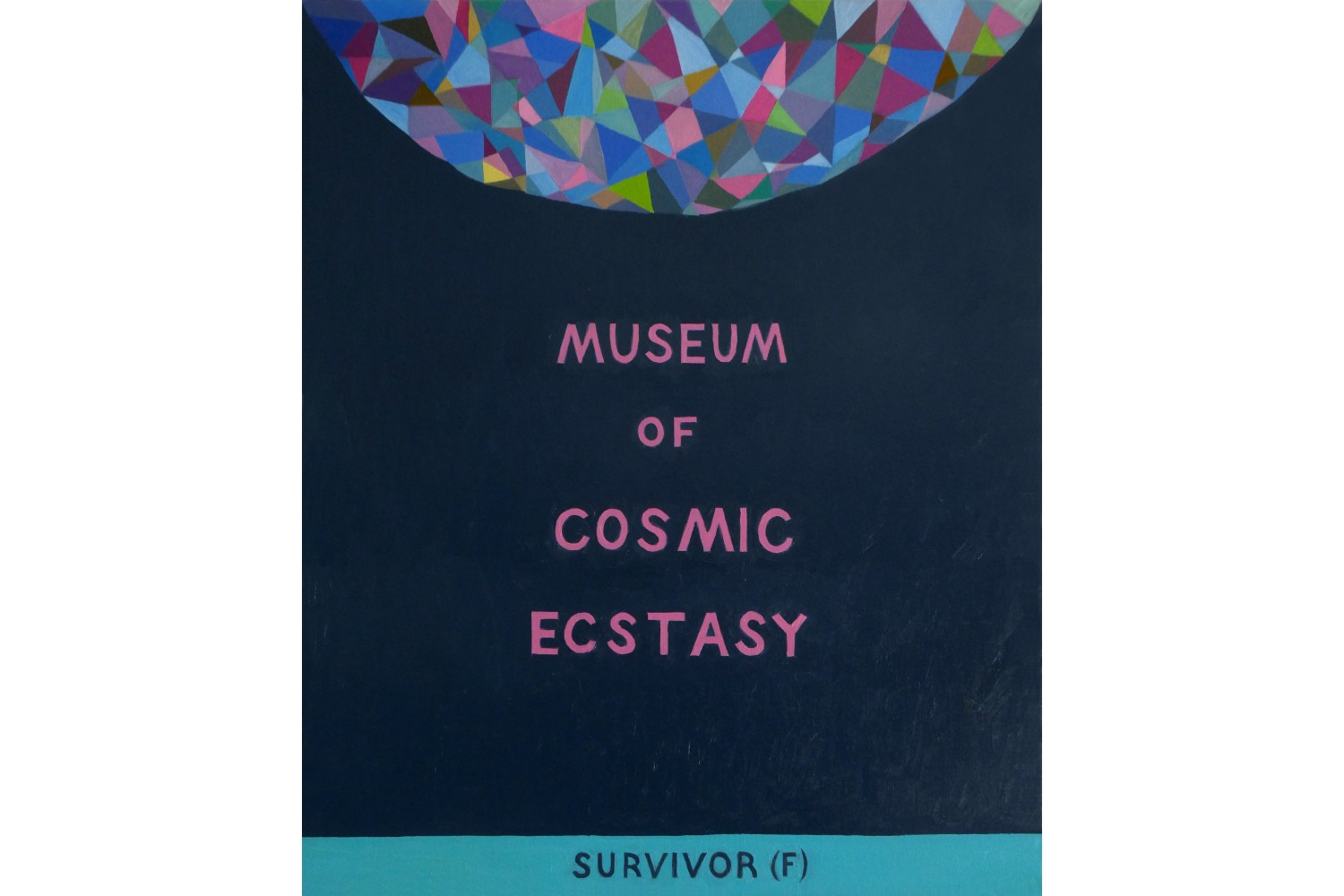

Among the many futurisms, Afrofuturism and related theories do the heavy lifting in this show. The collective Black Quantum Futurism, for example, is included with a video work that imagines a Black secret society that unearths time capsules containing ancient technology to hack into colonized timelines. And then, an entire floor at Museion is dedicated to Drexciya, the myth surrounding an underwater civilization of descendants of enslaved pregnant women who were pushed off America-bound ships. The myth has been propagated by the eponymous techno group on record sleeves and in track titles. Rhizomatic and fractal, indeed: from the loneliness of post-socialist Yugoslavia to the Black Atlantic, from Sinofuturism to the slow cancellation of the future, “HOPE” is fragmented and never haunted by grand narratives.