This text is about the exhibition “In and Out” by my husband Kaspar Müller at Galerie Francesca Pia, in Zurich. I write from the perspective of someone who appreciates Kaspar’s work, but has a personal relationship with the artist, which hopefully makes for an interesting viewpoint.

For “In and Out Kaspar” stages a hermetically sealed, stage-like space that appears completely permeable. The sculptural objects; the toilet paper paintings, the glass orbs, the chandelier and the 3D print of a wine catapult remind Kaspar of props or stage sets, the drawings of figures. Promising an ostensible festivity, the exhibition is arranged as if it were approaching a punch line.

In their industrially standardized appearance, the motifs of the exhibition appear as familiar, as they appear redundant to the viewer. Sentimentality can not unfold here because even the transience of the motifs and objects appears preserved and controlled. Thus, the exhibition is more maintenance than memento mori its works remain superficial and inaccessible. No narrative that connects the objects in the exhibition, so nostalgia cannot arise, because nostalgia lives in narrative. Maintenance, from the French “main tenant”, could be understood here as the need for a material connection, as a form of reconfirmation.

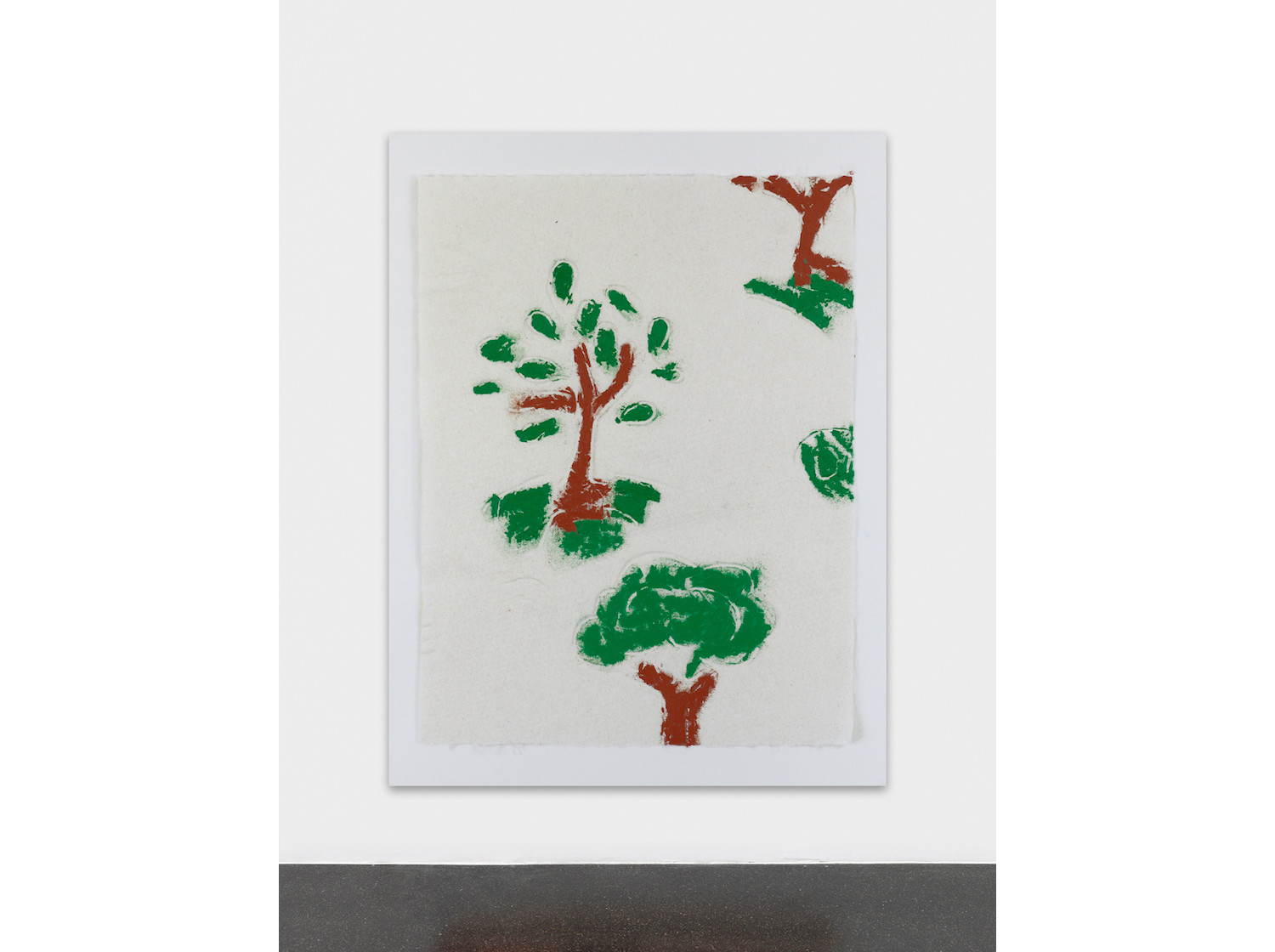

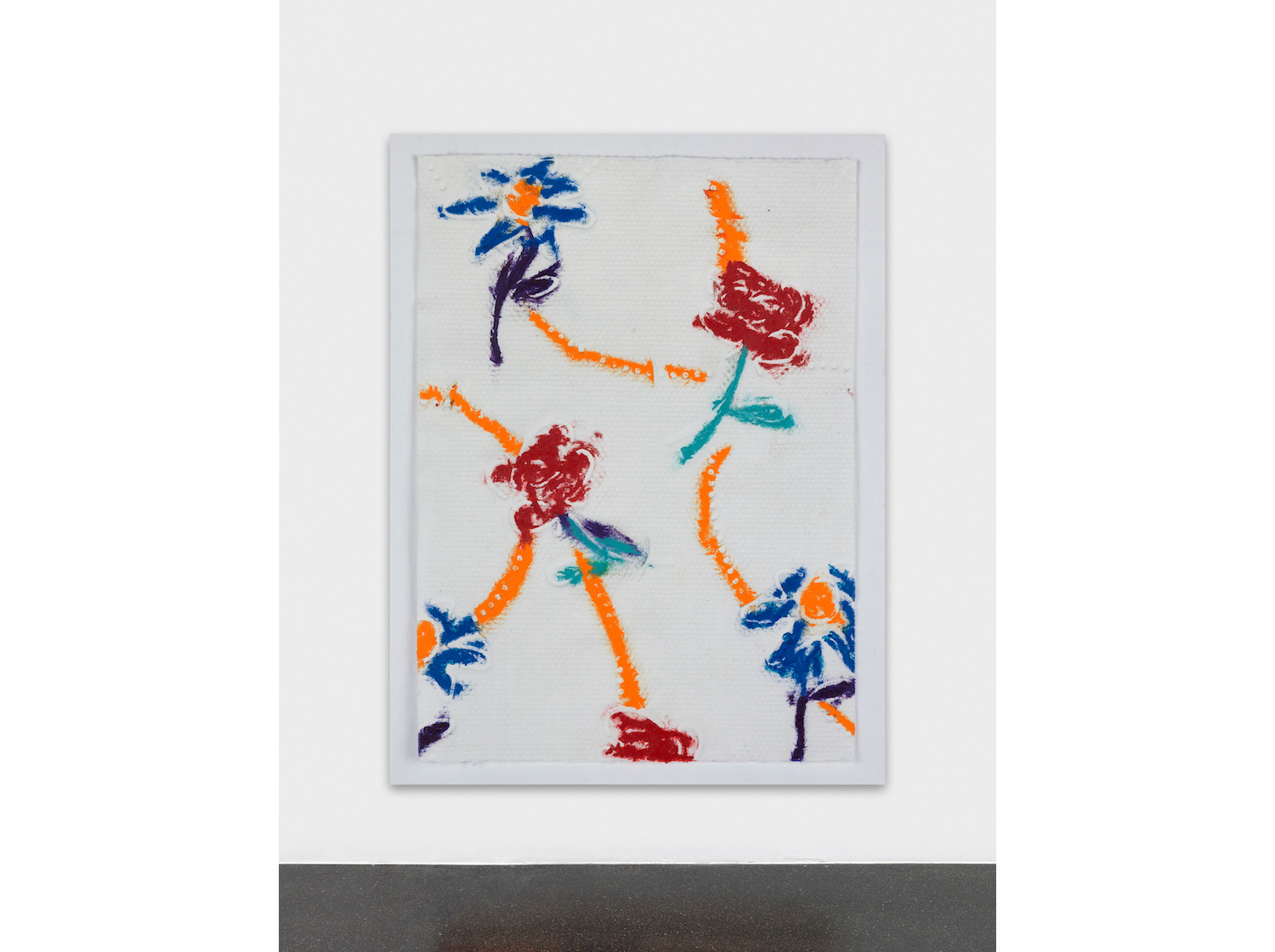

Another key word, besides maintenance and sentimentality, to facilitate access to Kaspar’s work in general and in this exhibition in particular, is the term of the mandala. A mandala acts as an indicator of transience and submission. The mandala (Sanskrit: sacred circle, center, essence) is mentioned for the first time in Indian Buddhism. Western consumerism has appropriated the mandala – today you can find mandala coloring books for adults in stores, which are offered to compensate for stressful everyday life. The meritocratic idea of self-optimization suggests that we first have to actively exhaust ourselves so that we can then actively regenerate again. This stands in direct contrast to the original idea of the mandala, to be aligned to a center point, having a radial balance. The toilet paper paintings in the first room of the gallery, titled Mandala, 2020, provoke the cliché: “my child could do that”. In this case, it was actually the artist’s child, our daughter, who came up with the original of the work. She unconsciously recognized the emerging symbolic value and the profane beauty of imprinted patterns – mostly flower arrangements – on toilet paper. During the first wave of COVID-19, toilet paper became a signifier. Excessive purchases of toilet paper took place throughout the Western world. There were definitely comedic moments when Kaspar, like many others, brought packages of toilet paper home. But what does the disproportionate acquisition of toilet paper say about the mental health of our Western world? Behind the phenomenon lies what Freud described as the anal character. One could suggest that, over the course of this pandemic, the West has regressed to the developmental stage of a two year-old, returning directly to the anal phase. In Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious, 1905, Freud examined the function and meaning of the joke. He understood the joke as a technique of the unconscious, used to save conflict and simultaneously gain pleasure. In the anal phase, pleasure gain is mainly due to the control of bowel and bladder. Basically, it is the same in both situations, pleasure is gained the moment the punchline is reached, which then leads to relaxation.

Regarding the forthcoming second isolation, toilet paper hamster purchases could becom topical again. They are the preparation for anti-social acts – withdrawal to the toilet – and are inherently anti-social themselves: there are supposed to be people who really ran out of toilet paper, because there was none left in the stores.

The second element in the first room of the exhibition can also be located in this context: It is reminiscent of anal beads, a sex toy consisting of multiple beads attached in a row, which are inserted through the anus into the rectum and then removed with varying speeds, depending on the desired effect (usually during orgasm to enhance climax). In fact, the borderline theme of proximity and closeness is also expressed in the glass orbs. They are colorful and smooth, shiny, seductive and superficial. All of the latter, adjectives for visual attractiveness. At the same time, the glass orbs reflect and mirror the viewer, which creates distance and can be perceived as a form of rejection; there is no getting behind their surfaces. The production of these objects is characterized above all by immediacy. In the production of the spheres, the breath of the glassblower is directly translated into the specific, round form, without any intermediate steps. The sphere is one of the most important and well-known symbols of mankind. The variety of the round shape is infinite, spans all epochs and includes all continents. From the earliest cultures to the present, the sphere has represented the order of the world, its predictability and unpredictability. The sphere deals with the great riddles of our time: What is the cosmos, time, space, beauty, chance? These questions have determined human thinking for thousands of years. The round shape of the sphere is the perfect shape per se, no computer in the world can make a perfect sphere. In this context, it can be comforting to know that God gets angry when something works too perfectly.

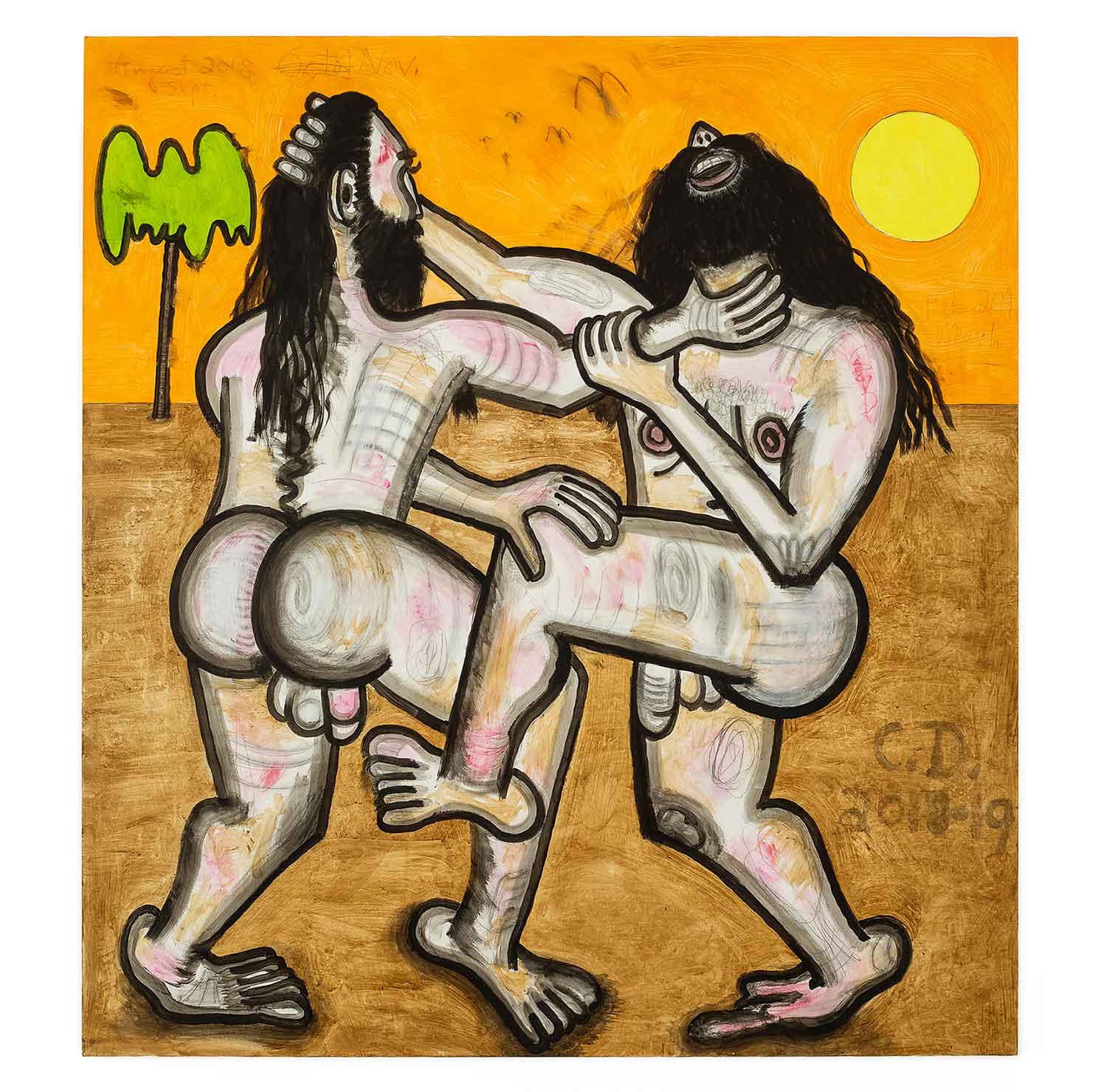

To what extent Kaspar pursues, illustrates or tries to cope with trauma, I cannot say. He feeds himself into the passive-aggressive cycle in which images are submitted to him. He encounters this dynamic in a performative act. He maintains the cycle by repeating it. This applies above all to the drawings in the exhibition, whose motifs are always figurative and often very explicit. He draws, paints over, processes and warps. He not only imitates the motif, but reproduces the technical structure again and again in order to understand the potential of the image outside of its flatness. Visually, this cycle of images is reminiscent of a feed, as if its production were determined by an algorithm. The drawings, therefore, are not executed from head to hand. Ultimately, in the exhibition is the work Deutsche Industrie Norm (DIN), attached to the wall with magnets; ink-jet prints of digital files, the data structure of which has been more or less superficially modified in apps such as Procreate, Photoshop or Concepts. Since working on these drawings, Kaspar has worn down three interchangeable tips of his digital pen to the metal tip hidden under the plastic coating and the cracks in the glass of his iPad screen have also increased. This iPad, the tool with which these drawings were made, was accidentally, but no less destructively, dropped on the floor by our children, several times. The resulting damage, Kaspar told me, produced irregularities that constantly required a slightly different movement to keep a straight running line. Each of the drawings emerged from three images: the digital file, the image on Kaspar’s iPad, distorted by the cracks on the screen, and the final printout. Without the cracks on his screen, as he himself says, he would not have had the macabre perseverance to make all these drawings and then print them out neatly on various DIN A2 papers under hours of supervision.

There is another motif on the floor in the second room of the gallery. Towards the end of the 16th century, at the end of the Renaissance, the Italian aristocracy moved their societies into closed rooms where chandeliers worked their festive wonder day and night. In 1661 the chandelier traveled from Milan to France. At the beginning of Louis XIV’s reign, everything revolved around the Sun King and his royal court in the middle of Europe; with him the most beautiful and noble chandeliers shone. The object of the chandelier is presented here as a standardized form. The chandelier as a form can always be viewed as its own contour, as a drawing. It precedes the negative form from which an identical product can be produced many times over in serial repetition of casts. In this respect, the shape of the chandelier is a perfect symbol for the connection between the bourgeoisie and industrialization. Behind ostensible festivity, Kaspar’s exhibition leads back to the topic of the material and its industrial form again, in a technocratic movement within his production that distinguishes itself from artistic individuality.

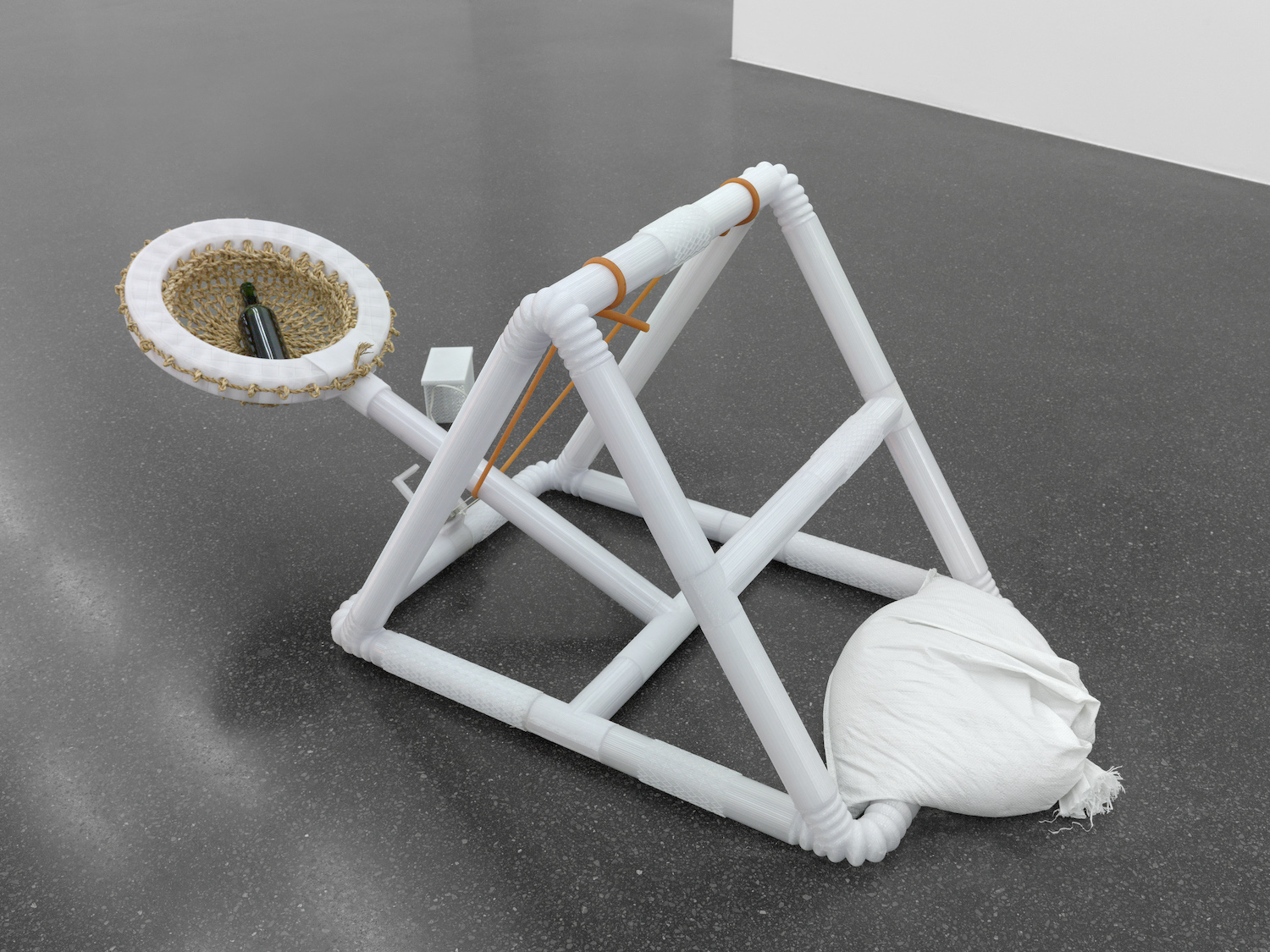

But enough of building up tension and, finally, to what could bring us relief: a 3D printed wine bottle catapult. This catapult is the perfect promise of a punchline at the end of an exhibition. It also leads back to the pictures in the first room, to the toilet paper paintings and the pleasure gained through relaxation after building up tension. Kaspar once said humor in his work has a mechanical character: “The viewer should laugh as if something has been broken. I am interested in an increase in failure that is inextricably linked to a system of representation. There is an implicit absurdity in the attitudes artists adopt to offset such misconduct. It’s like watching someone slip and pretending nothing happened.”

The young artist Iacopo Spini joined Kaspar in the conception of the catapult, which led to a collaboration in the design of the framework and the programming of the computer-controlled launching mechanism. The catapult also has its origin in a technical, spatialized drawing. It is controlled by a computer and the mechanism for launching it is programmed within it. A catapult is usually used to fire projectiles from one room to another, using mechanical energy to accelerate sharply from a resting/stationary position. In this exhibition, the catapult represents iconoclasm and the abolition and destruction of sacred images. What remains is the ruin, the destruction of the other, the image; a potential work of art.

And so, the final punchline is absent. What we have left is our individual weariness, more or less distinct than before we came here, more or less distinct after we leave.

– Tina Braegger