“Listening In” is a column dedicated to sound, music, and listening practices in contemporary art and its spaces. This section focuses on how listening practices are being investigated and reconfigured by artists working across disciplines in the twenty-first century.

Peter Jericho’s Quarantine Concert, Experimental Sound Studio, April 30, 2020.

“I just want to know if I can be seen … and can I be heard. Is everybody hearing me? I first want to know that I can be heard and seen.”

— Peter Jericho, The Quarantine Concerts, April 30, 2020.

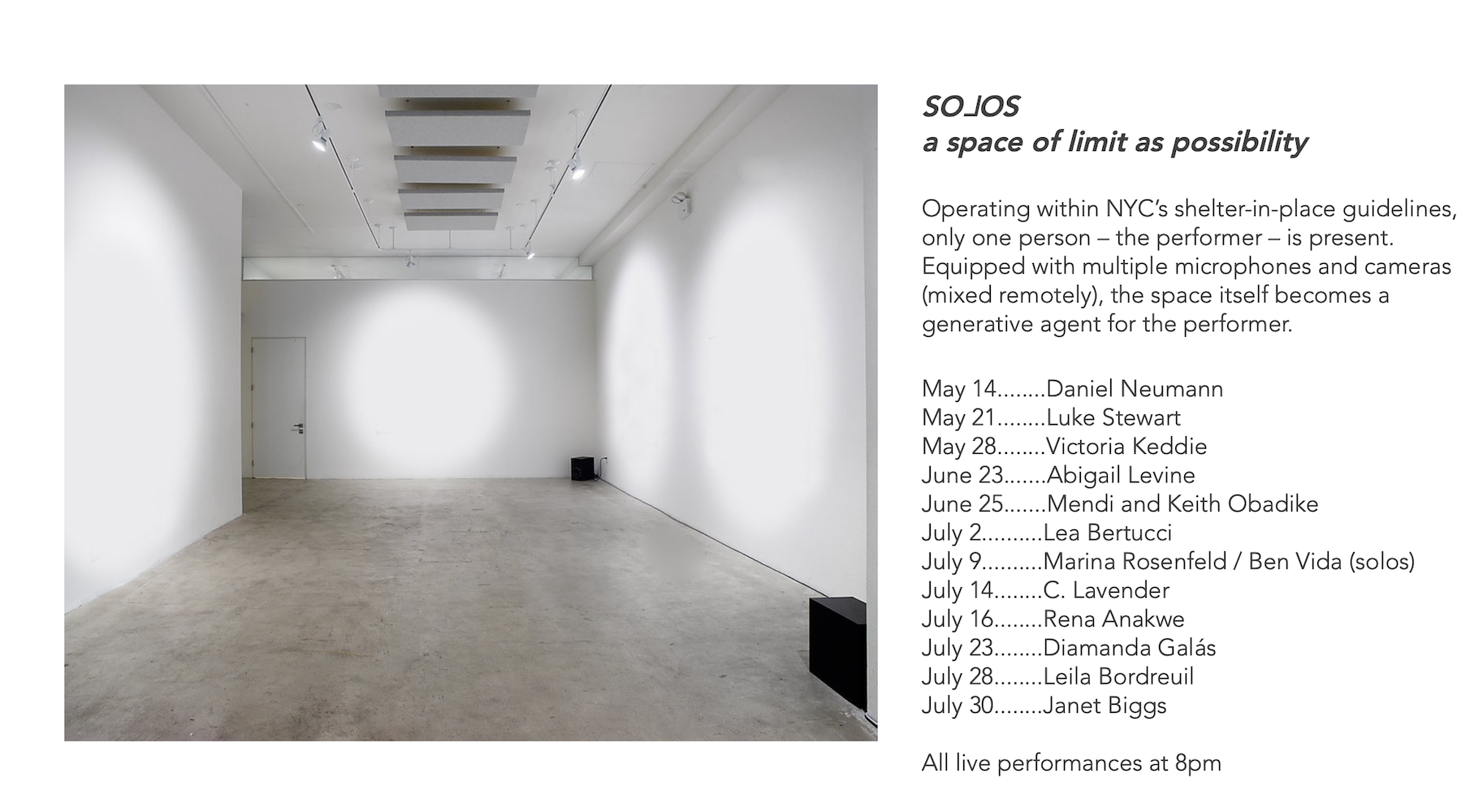

During these months of the COVID-19 pandemic that has produced so much loss, suffering, isolation, and uncertainty, arts initiatives and institutions have provided online platforms that offer some continuity in the experience of music: Experimental Sound Studio’s (ESS) The Quarantine Concerts (TQC), Issue Project Room’s (ISSUE) Isolated Field Recording Series (IFRS), the Fridman Gallery’s SOLOS, and The Kitchen’s Kitchen Broadcasts, among others. Each of these organizations program and host live experimental/contemporary art-music performances and are otherwise central to the scene(s). They invest in the “live” of their stream series and, distinct from other online music-making and transmission practices, do so as an alternative to fleshly assemblies in performance spaces; that is to say, they aim to invoke what we miss about them in terms of attributed values (“spontaneity, community, presence, and feedback between performers and audiences,” as Philip Auslander puts it) and social capital. But what is “live” about these livestreams?

Core to liveness across its manifold and contradictory specificities is a craving for being connected, for being in touch with others and with the world, for presence and for being present. Always scheduled at specific times, these transmissions bring forth a temporal co-presence, when we “listen in” simultaneously, getting “in sync” in spite of issues with latency and buffering lags. And yet, the meaning of liveness and how it manifests — the forms that it takes and the modalities of engagement it brings forth — varies in important ways.

LoVid’s “April”, ISSUE’s Isolated Field Recordings Series, June 10, 2020.

Among this set of initiatives, ISSUE’s IFRS distinguishes itself by streaming commissioned field recordings rather than performances. But even this endeavor is framed as “almost live”: the recordings are original works that respond to “artists’ current conditions,” and have been recorded “live” on the day of streaming. In the other initiatives, the transmission is live: performance, broadcasting, reception, and recording take place in near “real time” and performers are, too, in sync with their online audience. In the case of Kitchen Broadcasts and TQC, performers broadcast live from their homes — as The Kitchen puts it, artists “connect from their homes to yours” — while, in SOLOS, artists perform from, and are present (and alone) in, the empty gallery space.

Greg Fox, Kitchen Broadcast, April 2, 2020.

But mere simultaneity, or the knowledge of simultaneity, does not guarantee a live vibe. “What is crucial,” in the words of Tara McPherson, “is not so much the fact of liveness as the feel of it.” Some of the series’ platforms (e.g., Facebook Live, Vimeo) allow the broadcaster to enable viewer chat and comments; TQC, in particular, encourages this form of interaction among participants as they watch the transmission on Twitch TV. The chat itself becomes a lively stream that, as a participatory forum occasioned by the live-streamed performance, enhances the sociality of the online event as a gathering. The behavior of individual artists also affects the perception of liveness. For instance, in their home-based contributions to Kitchen Broadcasts and TQC, Greg Fox, and Peter Jericho explicitly address the situation — the pandemic, the livestream, the people who are watching — to establish an intimacy with the event’s participants that exceeds the fact of the live transmission.

Lea Bertucci, excerpt from a live set with flute and tapes.

The candor and humor of these direct addresses suggest a familiarity, a community that preexists online co-presence. The livestream, then, also offers a virtual reunion of sorts, or an articulation of a community that transcends each individual series. Here, New York-based Lea Bertucci, by contributing to no fewer than three livestream performance series, provides a case in point. And, in addition to highlighting the importance of social networks and their technologies of gathering, these livestreams demonstrate their fragility, which manifests in lost connections and frozen videos, technical issues that interrupt synchrony in ways that are unevenly unshared. Such technical fragility echoes the uncertain future of the performance infrastructures where this community of practitioners usually gathers. In a sense, these livestream series are meant to keep the scene, the community, the practice alive, for the time being but also for times to come. In addition to making sure that “loss of mobility does not have to mean loss of community” (TQC Chat Policy), “aliveness” in the case of IFRS, Kitchen Broadcasts, and TQC also involves fundraising to support artists, many of whom are in financial risk.

The insistence on the live, on the just made — hence the performer’s laboring for you and, in the performance series, in front of you — is connected with the request for “donations” for the performers. This connection is tacit in the case of IFRS, which asks for economic support for ISSUE’s commissioning projects, and Kitchen Broadcasts, which provides the Venmo, Cash App, or PayPal usernames for the performers in its lineup. More directly, ESS asks its audience members to think of the $5 donation “as if it was a cover for a concert,” reminding them to “DONATE to live artists making live music!” in the chat during performances. This practice awkwardly recalls charity, precisely because of the compromises necessary in a situation where “live” and “music” work against each other. I refer to the ways in which the allegiance to “real time” — simultaneous transmission and reception of the performance as it happens — demands lossy compression, rendering impossible an analogous “fidelity” to the quality of sound one would experience in a shared performance space, or to the performance as it sounds and is captured in the space of the performer. SOLOS, in contrast, clearly marks performing as work: there are tickets and passes — upon request, there’s free access if you can’t afford it — and artists perform in a staged, curated way.

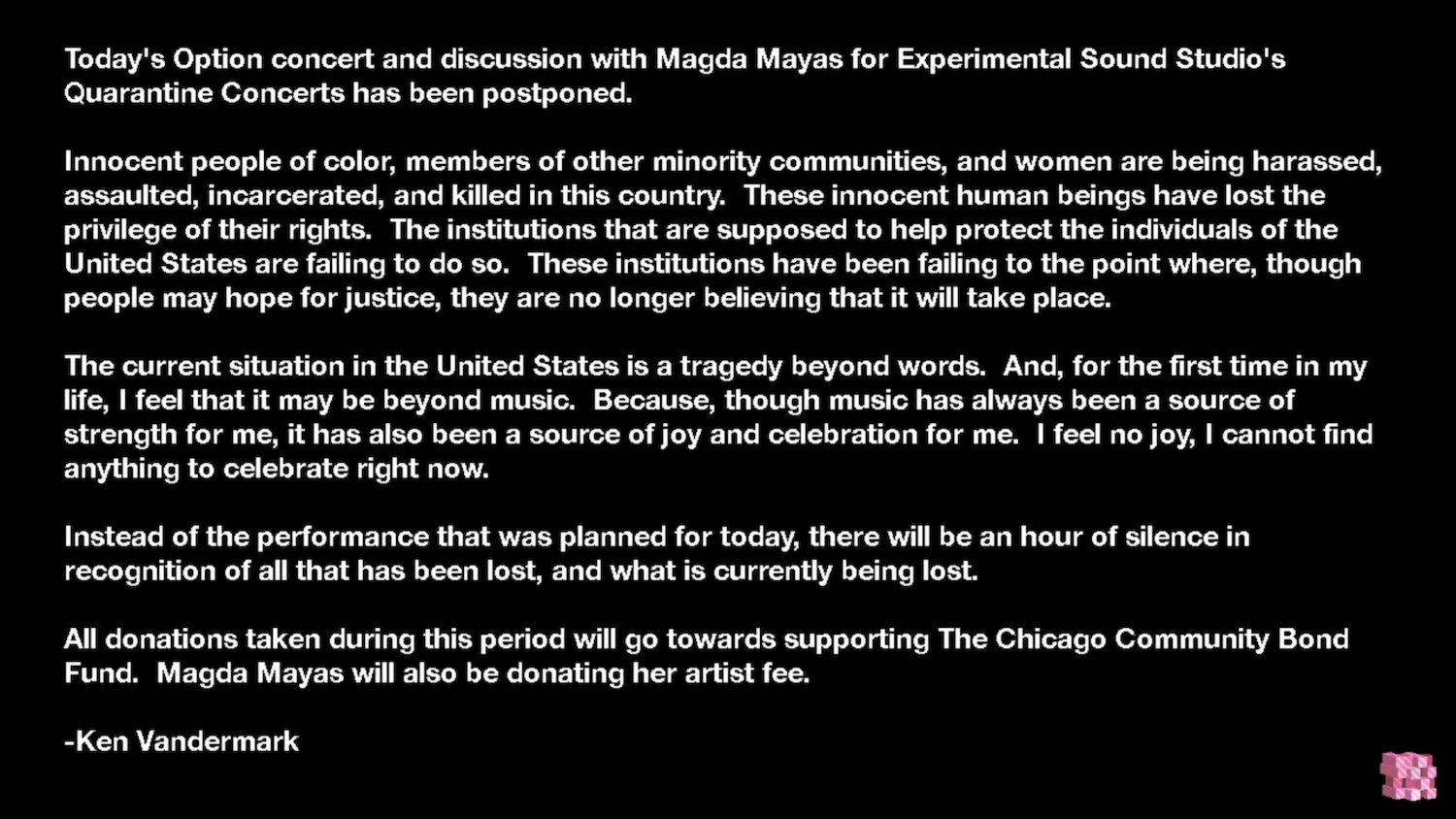

In conclusion, I would like to call attention to one more dimension of liveness: being in touch with and touched by “life,” by shared social realities as they are being lived during this time of livestreams; as I write in early June, our governing social reality has shifted from an exceptional spring of mass illness to an unprecedented summer of mass protest. Three months of listening in place, at home, have yielded to a feverish return to gathering in the street. Several livestreams have been cancelled.

The wave of mass demonstrations sparked by the racialized killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade, and Ahmaud Arbery has instilled a renewed and shared sense of urgency, of living a “situation” that cannot be denied — it is engrained in my neighborhood’s affective landscape, via rallies, marches, placards, graffiti, leaflets, chants, and the constant sounds of helicopters and sirens. Neither the gallery workers nor the artists could travel to the Fridman Gallery without violating New York City’s curfew and, hence, without being at risk. Georgina Born has referred to a musical public as “a congregation of the affected, of those participating in or attending” an event. The cancellation of streamed concerts reveals its community as part of a larger, affected “we,” and, as the closed listening of the quarantine has given way to open shouting in the street, we might discover a deeper kind of “live” listening, listening for life and hearing demands that affect us all.