Dance Office is a column dedicated to contemporary dance and performance art.

“Dance, dance, or else we are lost.” So goes the iconic quote spoken by Pina Bausch, the choreographer who is widely regarded as the high priestess of German Tanztheater (dance theater). Born in Solingen, Germany, in 1940, Bausch trained at the Folkwang School in Essen under German dance pioneer Kurt Jooss, and at the Juilliard School in New York. She then returned to Germany to become a founding member of Jooss’s newly formed Folkwang Ballet before taking up a directorship at the Wuppertal Opera Ballet in 1973, which later became known as Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch. Here she created performances that have become milestones of dance history, developing her own individual approach to movement that emphasizes emotional expression and the human experience over traditional rules and styles of presentation. Seeing a Bausch work is like entering a different world, one populated with disparate vignettes of characters who, although sometimes surreal, are always relatable. Shortly after her death in 2009, she was immortalized in Pina by German director Wim Wenders, which showcases excerpts from her works and includes interviews with her loyal family of dancers about their experiences working with the modern dance legend.

Unlike other companies of twentieth-century pioneers that stopped touring regularly upon the passing of their founder — such as Merce Cunningham Dance Company in New York, which has been replaced with a charitable trust preserving and licensing his work for performance by other organizations — for the past ten years Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch has faithfully sought to keep their namesake’s oeuvre alive by continuing to perform restagings of her work in theaters across the globe. But of course, when a company’s direction has been inherently centered around the intuition of one visionary director, it becomes difficult to continue in their absence.

“I was called to create sustainable conditions for the company to finally be able to shape its long-term future after ten years without Pina,” says Bettina Wagner-Bergelt, who assumed the position of artistic director last year. Since her appointment, Tanztheater Wuppertal has developed a diverse repertoire that combines both revivals of Bausch’s choreographies and upcoming commissions by contemporary artists such as renowned Belgian choreographer Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui — “whom Pina liked very much” — and American creator Richard Siegal. “My starting point is curiosity, courage, and aesthetic innovation. These are basic characteristics of Pina Bausch’s works and therefore requirements for revolutionary new creations that are made for the company.” But despite this welcome, innovative approach, preserving and presenting the legendary works made by Pina Bausch herself is still of paramount importance. “Most of them are masterpieces of contemporary dance. The new genre of dance theater that Pina Bausch created has influenced generations of choreographers and artists in all fields,” says Wagner-Bergelt. “Her works have started to be regarded as classics, and I think we need to make sure this doesn’t happen. Her work, her subjects, and her message have to stay fresh and surprising for new generations that encounter them.”

With this in mind, in February of this year Tanztheater Wuppertal will be reviving Pina Bausch’s 1977 work Bluebeard. While Listening to a Recording of Béla Bartók’s Opera “Duke Bluebeard’s Castle”. Despite its twenty-five-year absence from the company’s repertoire — predominantly due to restrictive copyright laws surrounding the use of Bartok’s opera which have now been lifted — it is regarded as one of Bausch’s masterpieces alongside other landmark creations such as Café Müller and Sacre, her take on Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. “It is a tense and demanding piece which is emotionally overwhelming,” says Wagner-Bergelt. “It leaves you breathless.”

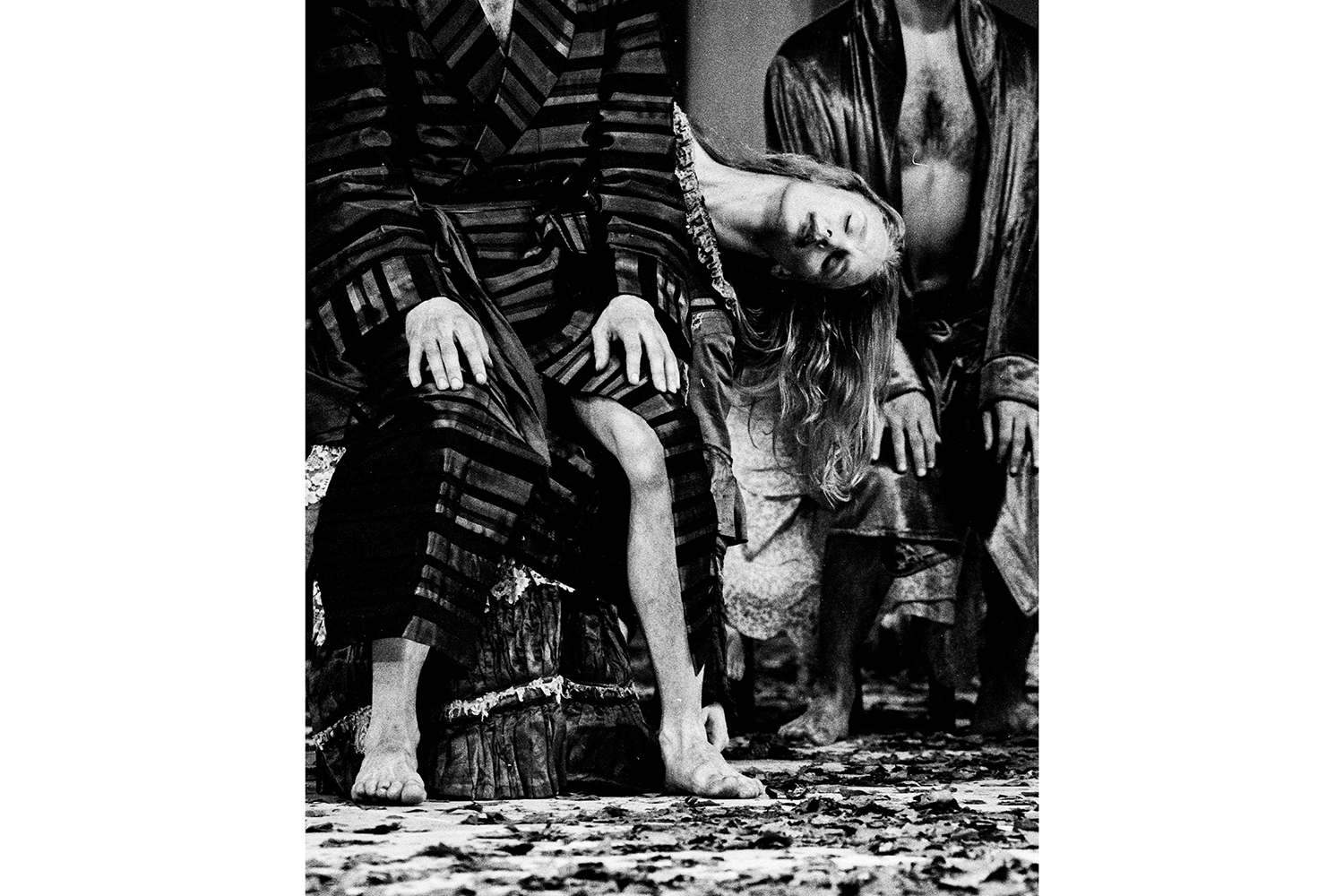

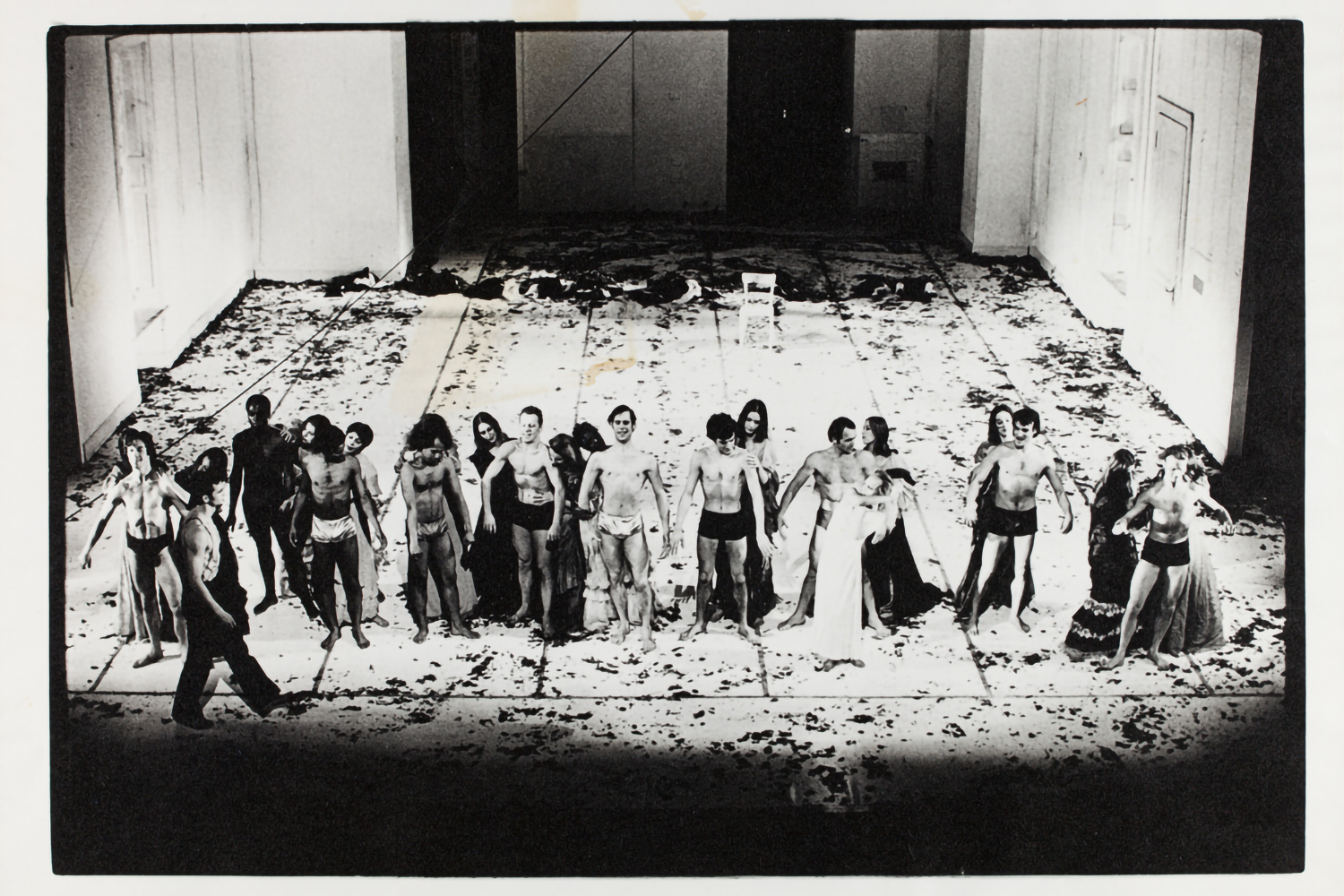

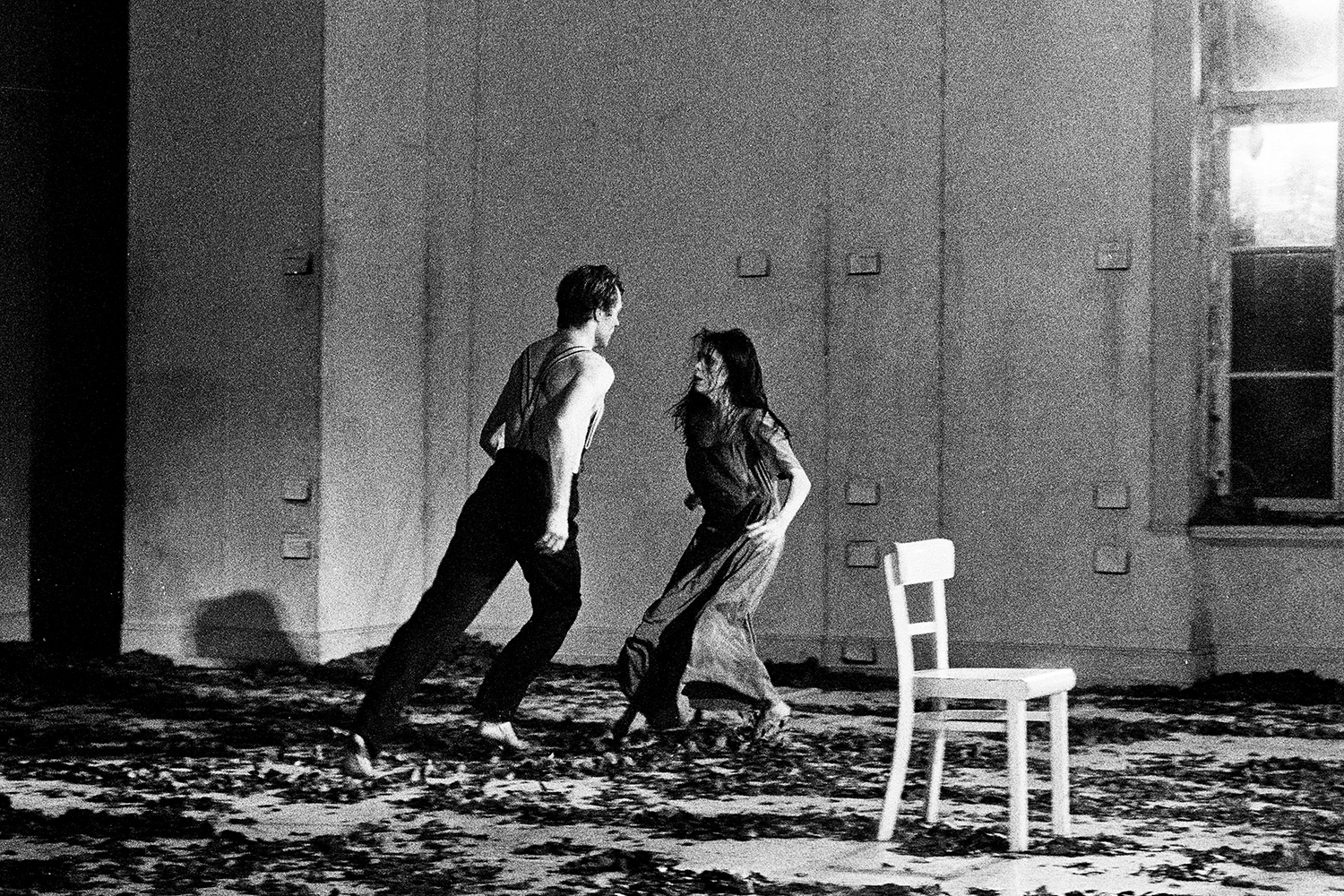

Performed on a stage covered in rustling dried leaves, Bluebeard is inspired by the story and music of Hungarian composer Bela Bartok’s classic opera Bluebeard’s Castle. “The piece deals with the character of Bluebeard, who murders his wives. The last wife, Judith, is curious and finds out about the fate of her predecessors,” explains Wagner-Bergelt. While Bausch’s interpretation does deal with this same narrative, the way it presents the story is more abstract and dissected than the original opera. Two main protagonists play Bluebeard and Judith, engaging in raw, violent exchanges as the rest of the cast reflect their emotions and psyches in a Greek chorus-like manner. The character of Bluebeard is in charge of proceedings, and with his finger on the button of a tape recorder, stops, rewinds, and repeats Bartok’s original score, hence affecting the actions of the other dancers on stage.

Metaphorically alluding to themes such as power and manipulation, this aspect clearly reflects Bausch’s psychological approach to Bluebeard, and her desire to deeply analyze the relationship between the central characters as well as their individual psyches. Wagner-Bergelt believes that these themes are extremely relevant, and that the piece will resonate with modern audiences despite the fact it was choreographed forty-three years ago. “It is absolutely contemporary in how it addresses sexual obsession and violence,” she says, alluding to contemporary issues such as #MeToo. “I’m very curious to see how the public will react to it today.” Barbara Kaufmann agrees. “It’s very relevant in terms of manipulation and interhuman relations.”

Kaufmann, who joined Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch as a dancer in 1987, is one of the lead restagers for this revival of Bluebeard. She began the transition to a more directorial role back in 2001 when Bausch asked her to become a rehearsal assistant for Sacre. “I would sit next to her, listen and observe,” explains Kaufmann. “She told me that you have to look everywhere. Because as a dancer you only have a perspective from inside the work, from your own standpoint in the piece. But when you look at it from the other side of the stage you have to learn a lot of different aspects, and understand the bigger picture.” When talking to Kaufmann, she constantly peppers her speech with anecdotes of what Bausch told her over years of working together. For her, even since her death in 2009, Bausch still maintains a constant presence in the company’s rehearsals. “But it’s not constantly like we are saying ‘Pina said like’ or ‘Pina thought like this.’ Because we actually don’t know what she would have thought nowadays. We have to really go from the source that we have, and this heritage that we carry inside. We have to take responsibility and say that this is the way we do it. We’re not changing the pieces in their form or their movement, but we have to revive them with the people we are now.”

Kaufmann is working alongside fellow former Tanztheater Wuppertal dancers Helena Pikon, Beatrice Libonati, and Jan Minarik to stage Bluebeard, all of whom previously performed the work. Libonati and Minarik were also part of the original cast and creation. Together, they work with video footage, their “show bible,” which includes handwritten notes, and their own memories to piece together the work for a new cast of twenty-first-century dancers. “For me, the interesting thing is to bring all these things together, because we all have our own memories and our own emotions that we connected with when we did it,” says Kaufmann. “In the piece there is always a space for you as a performer to use your own imagination and build up things for yourself.” When you take into consideration that one of Bausch’s most famous quotes was “I’m not so interested in how they move as in what moves them,” it makes complete sense that in order to honor her legacy authentically, the new cast of dancers for 2020 — which is a multigenerational mix of artists, some of whom met Bausch and others who joined after her passing — must put their own emotions and interpretations into the piece rather than just copy what others have done before them.

One such dancer is Emma Barrowman, a Canadian artist who joined the company in 2015. When asked what initially attracted her to working with Tanztheater Wuppertal, she says that she admired the company’s attention to the mindset, place, and state you are in when performing actions. “Whether it’s going for it with the most extreme physicality — because there are some dances you really have to push through — or quiet moments where you just smoke a cigarette on stage,” she explains. “This vast range shifted my perception of what art can be.” But there have been challenging elements of joining the world-renowned company. “At first it was really frustrating because I wasn’t used to dancing in water, grass, and mud,” Barrowman says, laughing, referring to the fact that Tanztheater Wuppertal’s oeuvre is full of choreography that brings the natural world into a theater setting. The leaves scattered across the stage in Bluebeard are a prime example, as is the iconic soil-covered stage of The Rite of Spring and the water-drenched set of Vollmand. “In Palermo Palermo we even have cheese, salami, and banana peels to contend with! So it can be very extreme.” But despite her initial frustrations, Barrowman has come to love this facet of Bausch’s work. “I came to realize that it’s part of the piece to see people struggling with these elements. You’re not supposed to dance perfectly on top of them. They’re there to disrupt you.”

Not only will the revival of Bluebeard in February be the first time it has been performed in twenty-five years, it will also be the first time the work has ever been performed in the United Kingdom, taking place after initial shows in Wuppertal at Sadler’s Wells theater in London, where Tanztheater Wuppertal enjoys the title of international associate company. “Sadler’s Wells first presented the work of Tanztheater Wuppertal in 1982 and, following a seventeen-year absence, Pina Bausch returned to our stage with her company in 1999. We have a close, long-standing relationship with the company and have presented them annually since 2012,” Alistair Spalding, artistic director and chief executive of Sadler’s Wells, said in an email statement. “Through her work, Pina promoted a whole new way of thinking about the art form. She also showed us the full spectrum of human emotion — a world of cruelty, violence, frailty, love and tenderness, mostly seen through the prism of the relationship between men and women. Bluebeard is one of her early, monumental productions. I am proud and excited to present its restaging to our audiences.” Spalding’s words are a testament to the timelessness of Bausch’s work, and how it can still be seamlessly presented alongside performances choreographed today. Yet another homage to her work will see the Pina Bausch Foundation collaborate with Sengali dance institution École des Sables. There seems to be little worry that the work of the high priestess of German Tanztheater will feel outdated anytime soon.