Mandy El-Sayegh’s research addresses some of the most burning questions that women (artists) have dealt with for decades: How does one situate oneself within a male-dominated art-historical tradition? Can one avoid using biography merely as an indexical tool? How do we disentangle female desire from male fantasy/voyeurism? How does one negotiate a relationship with the world’s hierarchical power structures to gain access?

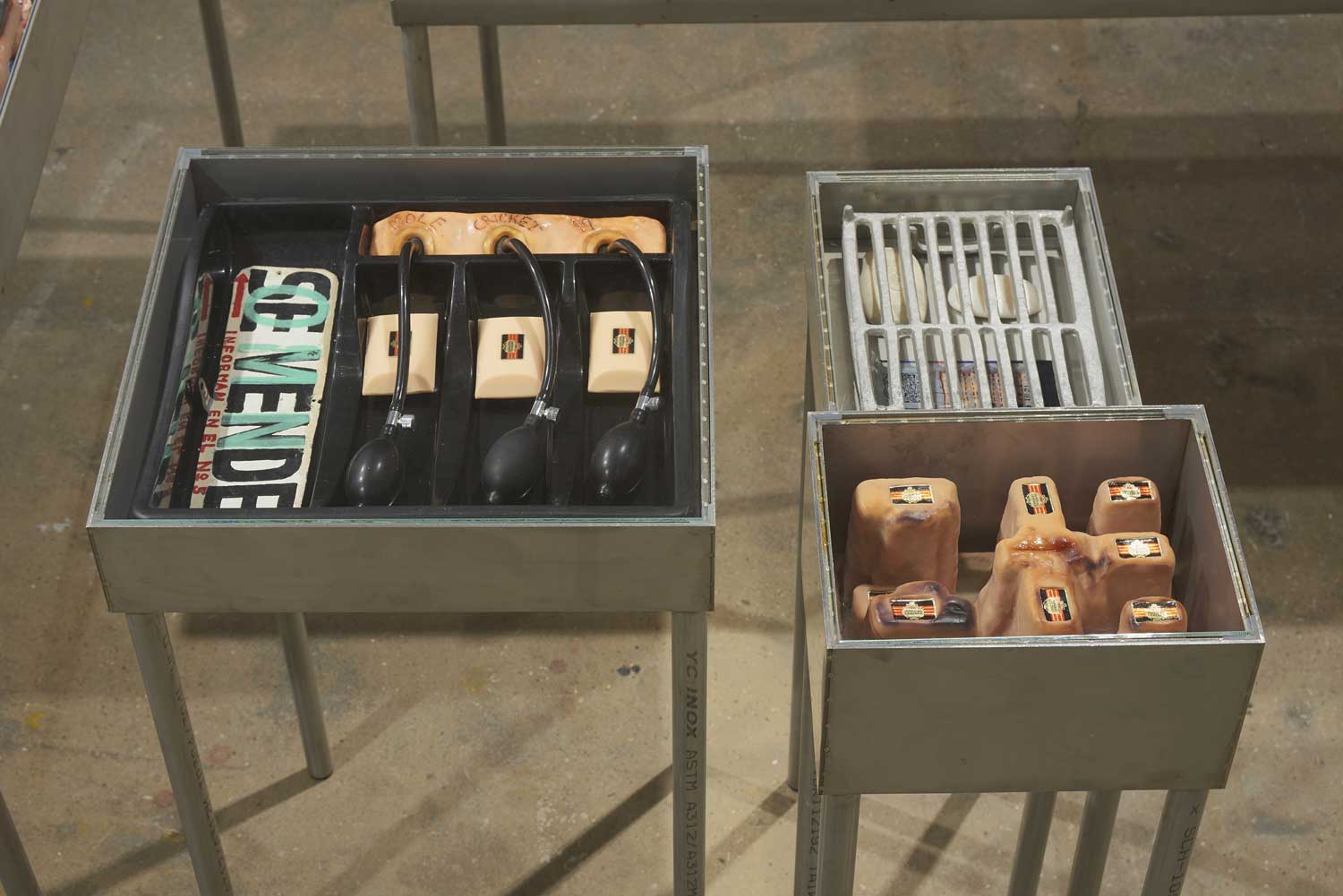

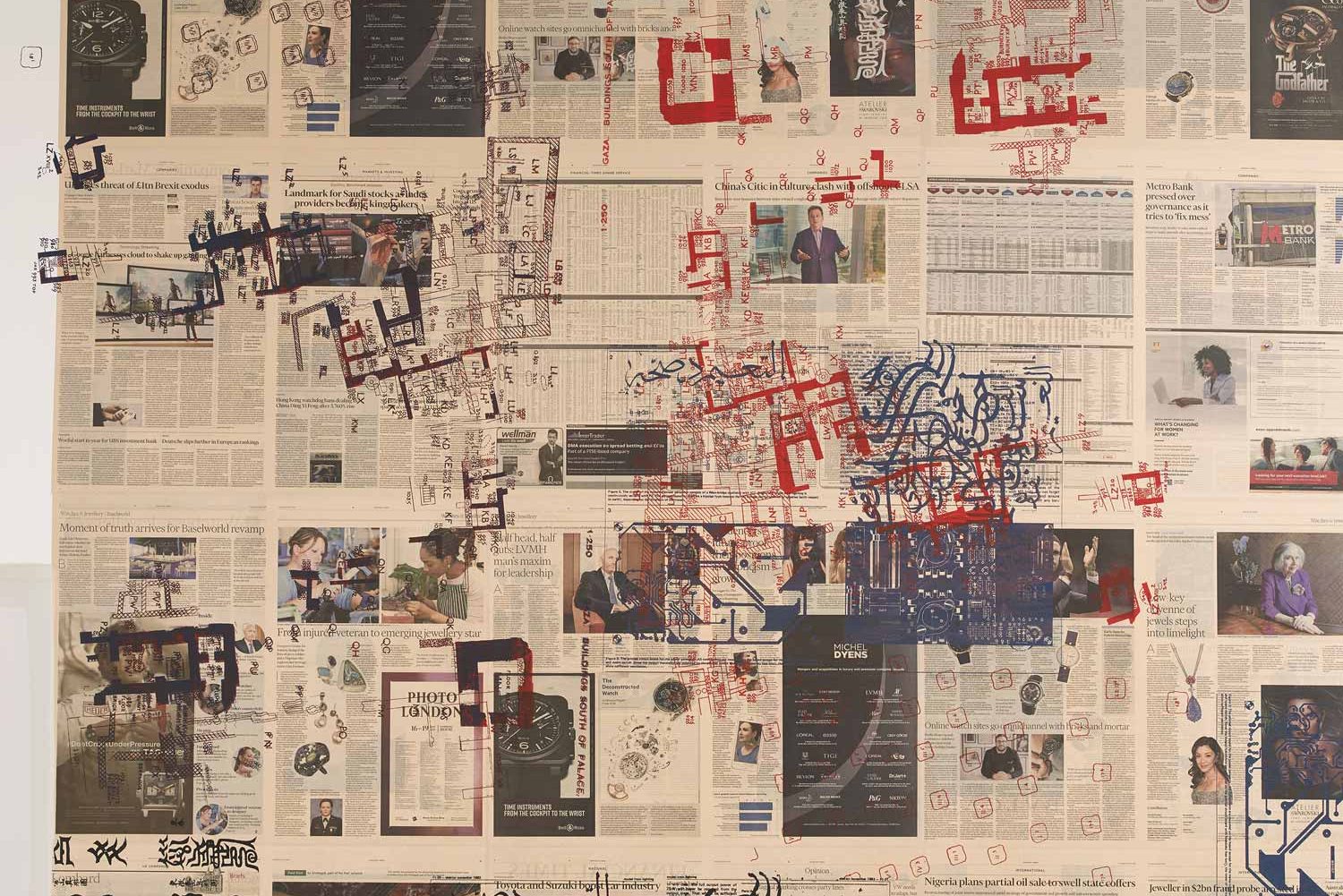

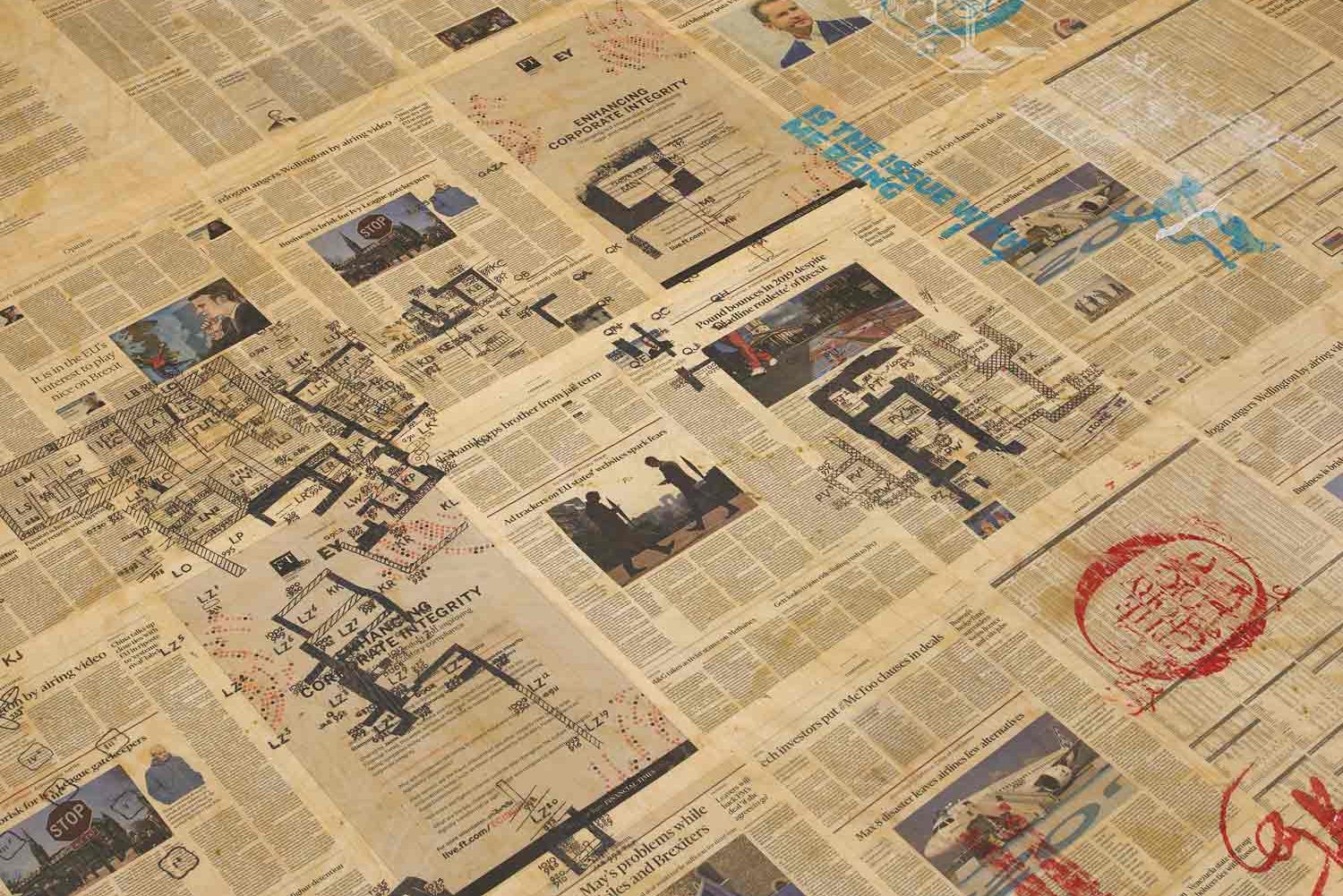

The artist’s exhibition at the Chisenhale Gallery in London is titled “Cite Your Sources.” This phrase — a quote from one of her former tutors at London’s Royal College of Art — ironically comments on how artists must be able to locate their production within established cultural discourses. The display features pieces from several bodies of work she has developed over the past decade. These include large-scale paintings from her “Net-Grid” series (2010–ongoing), the product of a lengthy studio process in which canvases go through screen-printing, gluing, assemblage, and painting stages; drawings inspired by found anatomical drawings of corpses and life-drawing sessions conducted in a morgue; and a selection of vitrines (rough metal, custom-made display tables) that present the raw material of her investigation, gathering miscellaneous ephemera and found objects. Each work seems to make specific art-historical references. Among the most obvious are references to painterly abstraction, combined with the use of some of the programmatic devices in Conceptual art, for example gathering, ordering, and indexing. Her practice positions itself in dialogue with a male-dominated logocentric art tradition. Yet the materiality of each object she collects and juxtaposes in her visual vocabulary, endows the works with an embodied and deeply emotional dimension that radically challenges such classifications. Paying homage to the title of the show, the present essay borrows its name from a book given to me by El-Sayegh: Sensible Ecstasy: Mysticism, Sexual Difference and the Demands of History by Amy Hollywood.1 This volume was crucial to learn more about the artist’s sources, which she uses to elaborate “a discourse that apprehends ‘other’ methodologies of thinking about a spirit, about suffering.”2 A key objective of Hollywood’s text is to flesh out the links between mysticism, femininity and hysteria in twentieth-century literature, philosophy, and psychoanalysis, to understand the role desire plays in subject formation. An important reference in the book is Hélèn Cixous, who theorized how the repression of desire causes a fragmentation within the self, which in turn leads to hysteria when the long-repressed impulse finally breaks free. The force with which this occurs opposes a threat to religious belief and practice. The madness associated with hysteria (typically by Freudian psychoanalysis) is ultimately the demand for the unification of fragments, for a wholeness or totality (tout) of subjectivity. 3 Hollywood focuses on the issue of fragmentation as the keystone to a complex narrative that addresses identity, eroticism, and sexual difference, intertwining her argument with feminist discourse. Building on Hollywood’s enquiry on fragmentation, El-Sayegh lucidly explains, “I want to work through the failure of unification and cohesion.”4 A utopian pursuit of wholeness or totality is at the base of El-Sayegh’s artistic project. If we examine her display tables, we encounter pieces of a deeply personal story — fragments of her identity.

These can be pieces of paper marked with calligraphy by her now disabled father or uncle still living in Malaysia, an old family photograph, or a magazine clipping that reminds her of her own memory of being breast fed. Seeking to distance her practice from a singular connection to her biography, El-Sayegh only partially reveals the story of her works, leaving the interpretation to the viewer’s sensibility. The objective isn’t to elicit forms of empathy with her story, but to incite viewers to make whole out of her fragments. In doing so, she provides the opportunity to have an active and embodied experience with her works. A feeling associated with this process may be a sense of anxiety. She explains: “Anxiety is […] a fragment. How can I give integrity or agency to this fragment, and how can I give it body and strength? How can it have a space that has more power and freedom than something that already exists and is legitimatized?”5 One of the strategies used to give agency to her works is the process of free association. For example, she uses association to build her archive, to assemble her display tables, to intervene on canvases, to guide her hand while drawing. She explains that there is a “productive ambiguity sought in the methods of free association […] which I believe is a way to think through the convention of identification.”6 Illustrative of the tension between desire and logic is a work made from an intervention on a medical drawing of a dissected abdomen (the head is absent) titled mutations in blue, white and red (too), 2018. The open core contains a written stream of consciousness that includes the phrases “feel free two state,” “he who states wtf,” “states of focus,” “too little too late,” and “I am done,” each segment forming a jigsaw puzzle of interiors. The text takes a cue from Richard Serra’s Verblist (1967–68), a drawing consisting of a list of verbs he compiled upon reflecting that “drawing is a verb.”7 The action that is implied in drawing, gathering, juxtaposing, is the connecting tissue of El-Sayegh’s research into totality, which she finds in the body, as opposed to language. Looking at our viscera as a source for understanding has ancient roots. Alchemists thought the stomach was a symbol for knowledge, the very place where information is dissected, fragmented, and re-elaborated into something new. Anthropophagists in 1920s Brazil claimed that Brazilian culture was cannibal and that it ought to devour, digest, and newly embody foreign cultures. From a biological perspective, the winding structure of the intestine mirrors the neural pathways in the brain. Our bowels move in tandem with our emotions, providing vital information to our minds. By placing written text where the intestines of this body should be, El-Sayegh displaces the locus of consciousness from the brain to the digestive system, which then becomes the site of enunciation. This action of displacement emphasizes the physical interior of the body and the emotions and feelings it generates. This important shift in register allows for the experience to be embodied and also imbued with Eros and desire. Through her research El-Sayegh builds on the legacies of artists who have sought new forms of expression, new languages that could accommodate marginalized or “other” subjectivities. The methodologies and vocabularies in her work resonate in the context of feminism, where artists have been battling to find a language compatible with a female subject (for example in the work of Carla Accardi or Betty Tompkins, among others). This struggle also applies to other abject bodies that do not conform to normative canons, whether in terms of race, gender, or sexuality. The erotic, embodied attributes that overflow from El-Sayegh’s works re-elaborate the very anatomy of communication, ultimately giving integrity and agency to her (and our) fragments.