The institutionalization of “art from the regions” is, arguably, the main tendency in Russian cultural policy. If private capital has demonstrated any responsibility for geographic inequality, the state has finally recognized contemporary art as an effective tool of omnipresent control.

Both the inauguration of the Garage Triennial of Russian Contemporary Art and the transformation of the Moscow branch of NCCA into a showroom for art from the periphery reproduce an imperial model of top-down administration. Artistic resources from across the country must first flock to the center to be infiltrated — and possibly become integrated into the international system. Against this common scenario, NEMOSKVA, initiated by commissioner and artistic director Alisa Prudnikova, attempts to challenge this hierarchical structure. Bypassing the metropolitan gatekeepers, the project invites internationally renowned curators to, in her words, “study the situation on the ground.”

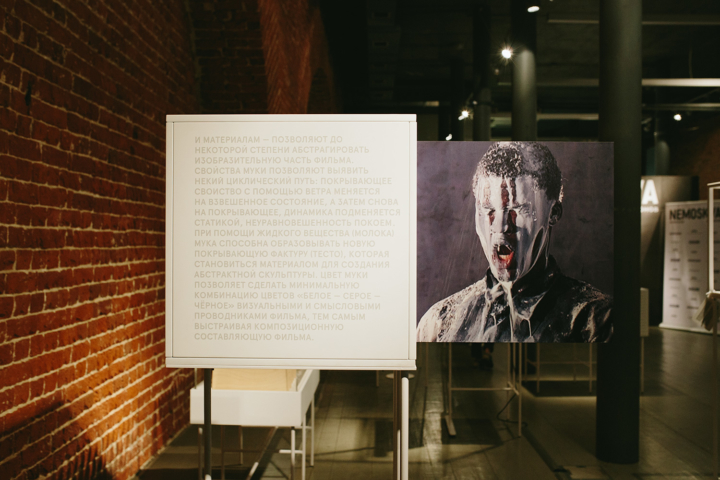

The orientation toward “ground” could also be read as a provocation in times when curatorial research more often finds complacency online. Instead of planes, NEMOVSKA relies on the railway system; instead of emails, physical encounters; instead of digital presentations, analog shows. In the first stage, three groups of curators and other specialists take an excruciatingly long Trans-Siberian train journey, making short stops in twelve major cities. In each location, the project unfolds over one day like an accordion, comprising portfolio reviews of local practitioners, symposia, solo presentations by curators, and, finally, the opening of a site-specific show. Titled “Big Country, Big Ideas,” this traveling exhibition, which followed the experts in two trucks, presented drafts of unrealized projects by artists from the inner regions of Russia (some of whom have already moved to Moscow). Overall, these prospective interventions and ethnographic studies, selected by Alexander Burenkov, give the impression that younger artists are very sensitive to local issues in their multiplicity, such as ecological sustainability, urban transformation, and exploitative labor conditions. Curiously, a disproportionate number of works address architecture: the disappearance of wooden temples (Vladimir Chernyshev’s The Abandoned Village), vernacular style (Artem Filatov’s Myth), and the (re)sacralization of secular buildings (Sergey Poteryaev’s Landschaften). However, none of the works speak explicitly of the colonial past, globalization, or the current core-periphery dynamic: instead of federalization, Russia tends to become a more unitary state.

Decolonial critique could have been a counterpoint to the rest of the project. As I learned during the journey through Omsk, Tomsk, Novosibirsk, and Krasnoyarsk, some of the members of the local art community were reluctant to participate, or even boycotted the project. Organizers of the successful Tomsk festival “Street Vision” did not want to be treated as “indigenous tribes” by so-called experts visiting from the mainland establishment. Unsurprisingly, the expedited process of portfolio review sometimes turned into an episode of X Factor, resulting in tragicomic miscommunication between the artists’ expectations and the experts’ inability to evaluate what could be otherwise considered design or documentary. While many artists understood open “crits” as a chance to evolve their exposure abroad, most of the proposals did not meet the discursive or qualitative criteria of contemporary art. The symposia and some of the lectures, organized by Burenkov and Antonio Geusa, similarly resulted in some misunderstandings between visitors and locals. While the former often spoke from a position of the public institutions’ responsibility, many artists and teachers supported a more meritocratic system. The incompatibility of discourses might have been a matter of privilege — rooted in a lack of sustainable education, international exchange, and functional institutions in the inner regions. The level of both works and discussions in Omsk and Tomsk differed significantly from Novosibirsk and Krasnoyarsk, which have more advanced infrastructure, and might point to issues of uneven geographical development within the country.

NEMOSKVA’s intent is, to paraphrase Dipesh Chakrabarty’s book Provincializing Europe, to provincialize the status of Moscow as an arbiter of taste. However, its fixation on regionalism inescapably verges on exoticization. Indeed, some of the artists overtly juxtapose themselves with Moscow’s commercialism, such as Omsk-based artist Nikita Pozdnyakov, who accepts the influence of his compatriot Damir Muratov’s “naive” art. Others see themselves as part of a digital realm that isn’t specific to a particular geography. The logic of negative theology that is used in the title (“nemoskva” literally means “not-Moscow”) only reproduces the gap between art center and periphery, and blurs different regions into one homogenous zone. In its current research-based structure, the project must face the “vertical authority” that permeates this hypercentralized and ill-connected country at its core: distribution of funds, social privileges, and cultural discourses are predominantly concentrated in Moscow. So it remains unclear how the local art scenes (and not particular individuals) would benefit from a couple of upcoming grand shows in Venice and Brussels. The database of artistic projects that is under construction sounds more promising in terms of establishing horizontal connections unmediated by the center.