Andrea Bellini: Let’s start with mistakes. Do you ever destroy your works?

Wilhelm Sasnal: Quite often. Sometimes I paint the same work five times.

AB: What is painting for you?

WS: It’s a nice way to spend your time.

AB: You often switch from one pictorial mode to another, from figuration to abstraction. Why is this? Is your intention to assert the infinite possibilities of painting? Or, in a certain sense, does this stylistic variety have something to do with the idea of the limits of representation?

WS: Neither. I can’t put it into words. I do my best. I do it for myself. That’s why I think committing mistakes is important. I justify mistakes.

AB: It seems that in each painting you always try to discover something new.

WS: Yes, and intuition plays a key role in my work. I wouldn’t like to be afraid of using something because I want to.

AB: How much time do you spend painting a work?

WS: I paint my works in one or two days. I like the feeling of finishing or closing something.

AB: Does this rapidity also have something to do with the idea of constant discovery?

WS: Maybe, yes, I think so.

AB: Your activity as a painter seems to have something to do with a process, with movement, and not just arriving at the destination of a particular style or language. Does the motion supersede any destination?

WS: I have no idea. There are no rules. It’s drifting somewhere. I don’t know where, but it is drifting. It’s not a controlled movement. Anyway, I like the feeling of moving my work forward, of not wasting time.

AB: In an article entitled “The Tuymans Effect,” published in Artforum (November 2004), Jordan Kantor wrote that “one of the strongest readings of Tuyman’s oeuvre has come from the thirty-two-year-old Polish painter Wilhelm Sasnal.” What do you think about that? Do you think your work can be read in this sense, as a kind of ‘working through’ of the implications of the Tuymans’s model?

WS: I don’t think so. I’m trying to work on my own, not in the shadow of Tuymans. I work in different mediums. He’s a very serious painter.

AB: What do you mean by that?

WS: I think he doesn’t have any distance from his work. I really like his works, but on the other hand, I have this distance. That is his way, but I am afraid of this in my own work.

AB: Can you explain this concept more clearly? Are you looking for a distance between yourself and your work?

WS: Yes, but I only realized that recently. I felt I was trapped by a fear of colors, and that I was walking a beaten path.

AB: So which painters have most influenced your work?

WS: Of course, Gerhard Richter and Sigmar Polke. There’s also a Polish painter who has been influential for me. His name’s Andrzej Wroblewski. He was painting in the ’40s and ’50s.

AB: In what ways do you think your work has improved or evolved since you started painting?

WS: When I finished my studies in 1999 I was pretty close to everyday life subjects. I would say that my painting then — and before — was quite close to pop. I worked for advertising companies and since then a lot has changed. But this is the drift that I mentioned earlier. I didn’t know the aim after two or three years of painting dark and heavy stuff. I would also like to make changes to my work in terms of subject matter. I think now I’m more aware of what I’m doing.

AB: You are a solitary kind of artist. It’s curious, but painters are often solitary by nature. I’m thinking about Anselm Kiefer and many other painters. You also develop your creative process in a sort of vacuum. Do you think that painting needs this kind of concentration and attention to privacy?

WS: No. It’s good to develop a style that is not too influenced by what’s around you, but there are no rules. Sometimes noise can help. It just happens that I don’t live in a big city and I don’t have contact with any kind of art scene. But I didn’t control that. It is not necessary. A counterexample might be Kippenberger, who was always surrounded by people and did great work.

AB: So could one say that there’s some kind of relationship between your personality and the things you paint?

WS: Well, there’s a certain percentage of intimacy and emotion in the work. But there’s also the matter of calculation and being aware of what you are doing.

AB: How do you choose your images? Is it random?

WS: Sometimes I find a subject that fascinates me and then I want to follow it. But it’s basically very random.

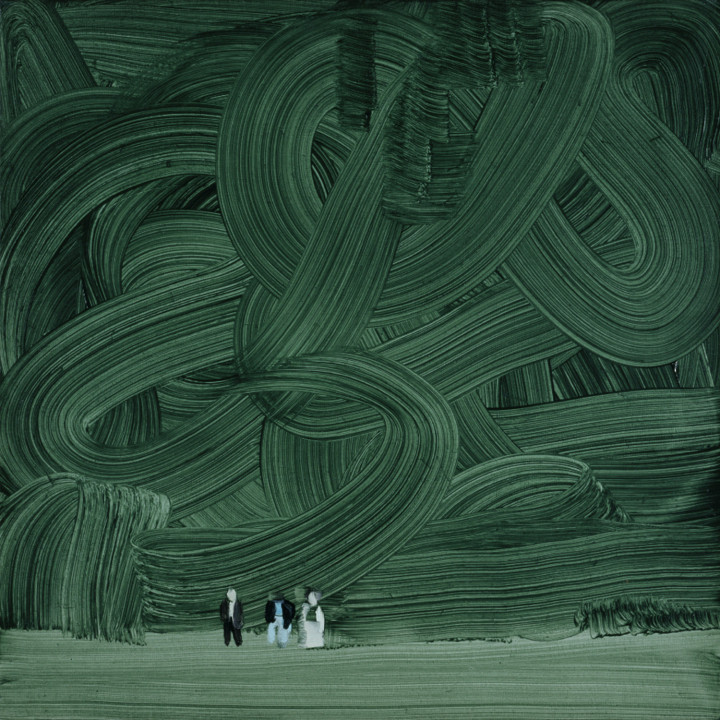

AB: And what inspires your abstract work?

WS: I don’t know if I’ve ever painted a completely abstract work. There is always some reference to reality. If it sometimes turns into abstraction, it’s because I see paintings as essentially very sensual. If they are vague, it’s because I want to give people many different ways to read it.

AB: How important are the titles of paintings for you? How do they interact with the images?

WS: Well, if you see a flower in a painting, it doesn’t make sense to give that painting a title because you can see what it is. Of course, when there’s a story behind it, it makes sense to give some kind of hint to the viewers. Sometimes you know nothing about the background of a painting and it’s impossible to interpret anything. But sometimes that’s not the case. I’d say half of my works are titled and half are not. When you juxtapose an image and a single word, there is poetry.

AB: Your paintings are largely based on preexisting photographs. Can you tell me something about your relationship with photography?

WS: Really the theme is more important than the medium. I take photographs to support my paintings, but I also paint from real life.

AB: Have you ever shown your photographs?

WS: Very few of them.

AB: What about the videos you showed in Iceland in 2005?

WS: There are three 16mm films. They are done with three love songs, like music videos, although maybe not in a strict sense. They are sometimes abstract images, although they are about moods, so they have something of a narrative quality. They are not so serious, although I do treat them seriously. This is what I sometimes lack in my work, which can be a little heavy. I always think of music and then think of the interaction between image and music. But I have no experience of showing them. I am still searching in this field. Music is very important for me.

AB: Is this also true for your painting?

WS: Maybe, but again, not in a strict way. I listen to a lot of music and I am aware of the strength of music. It’s parallel to art culture but it’s more accessible and I like that — it really influences people.

AB: In an interview Damien Hirst said that contemporary painting is very different from painting in the past, and that it is less important. What do you think about that?

WS: Yes, I think he’s right. Painting has lost the documentary role it had before. Other mediums have brought in a flood of images. My school always tried to drag the students’ attention to art history. When I finished my studies I was fed up with painting. I didn’t go to museums at that time because I was trying to escape from painting’s history. But now I feel free of it. It’s great when you can play with art history. I look at American paintings from the 19th century and I see the quality of action and narration. I’m quite surprised that people are still looking and searching for painting. This is something that is quite curious.

AB: How do you go about organizing your works in a show such as your 2005 one at Anton Kern Gallery in New York?

WS: That show is very special to me because I presented almost all the works that I did in Marfa,Texas. When I think of a painting show though, I don’t think in terms of a project.

AB: Not it terms of a project necessarily, but is there a relationship between groups of paintings by style, theme or size, for instance?

WS: Yes, I think there is. There is tension and interaction between them. For me, exhibiting paintings is like the act of painting itself. I think of sizes and intensity, and how they do or don’t work together.

AB: As we started the interview talking about mistakes, let’s close it with the worst possible question: who is Wilhelm Sasnal?

WS: I am trying to stay the same, but not as an artist.