Fear eats the soul

Of the two gigantic Buddhas that dominated the Bamiyan Valley in Afghanistan there remains nothing but detritus and heaps of dust. The news came from Kabul: the two statues cut into the rock more than fifteen hundred years ago have been condemned to death by the Taliban regime. Branded by edict, declared blasphemous and anti-Islamic, the two sculptures were razed to the ground. But bombs and grenades weren’t enough to reduce the thirty-meter high Buddhas to dust. It took scalpels, hammers and dynamite — a whole week’s work.

The power of the image

Seemingly light years away from our culture, the Taliban militia shares our obsession with images: iconoclastic fury hinges on a paradox, which also pervades the history of contemporary art and culture. In the very moment that it bestows the death penalty on images, iconoclasm, in fact, only confirms the hypnotic fascination of icons, acknowledging their power and threat. Similarly, since the beginnings of the 20th century, contemporary art seems suspended between a radical mistrust in the realm of the visible and a desperate need to grasp on to images to express its own skepticism of the world: contemporary art celebrates the hypnotic fascination of images in the very same moment in which it condemns the world of representation to death.

The image of power

Images have an invincible power, and power, in its turn, manifests itself through images; it feeds off of images. Power always maintains its distance, imposing a solemn detachment from the real: it is ready to strike, but always from a hidden refuge. This is why power needs images and signs that hold their guard up high, but that also preserve the strength and violence in the realm of the imaginary. This is the role of propaganda, with its posters, photographs, banners, icons, placards, choruses, slogans and rituals: propaganda is a mnemonic exercise which holds the memory and the threat of power alive, without exposing it, without inflating it, celebrating the distance between us, the subjects, and the head seated on the throne, standing next to his podium, little more than a blot of color in the distance, little more than an image. If, on the other hand, the head were a person of flesh and blood, sitting next to us, his power would be greatly reduced: there he could be attacked, shattered and defeated.

Power therefore stands behind the scenes. Like a director, he goes on stage only to reap approval, conquer the applause, or to instruct the actors, to bring them to order. Reflected in hundreds of images, power still tries to flee its representation, it won’t be caught: it disperses itself, opposing any analysis. The problem therefore, is not how to destroy an image: the problem is how to reach power, how to represent what is hiding behind images.

Lose your head

Marie Grosholtz was born on December 1, 1761 in Strasbourg, in France. She soon moved to Paris, where her uncle taught her to carve in wax. At only nineteen years old she entered the court at Versailles as tutor to Elisabeth, sister to Louis XVI. At the outbreak of the French revolution, Marie found herself in gaol, condemned for her relationships with nobles and sovereigns. In the meantime the guillotines of Paris began to make their first strikes, and during The Reign of Terror, Marie was forced to make funeral masks for her friends and companions at court: one by one she transformed them into waxen specters. In 1795 Marie Grosholtz married the engineer François Tussaud and won the name of Madame Tussaud, with which she entered history. Her name immediately evokes images of manikins frozen in theatrical poses and disseminated in the homonymous and extremely famous rooms of the wax museum in London.

Illegitimate child of the French Revolution, the Madame Tussaud Museum involuntarily delivers a severe blow to the rhetoric of power. At Madame Tussaud’s, as in any wax museum, everything is immediately accessible, everything is on the same plane, upheld through a deliriously democratic principle: the powerful are portrayed next to the stars, Elvis stands a few meters away from Marie Antoinette, Hitler next to Dante. History is subjected to a levelling process, a temporal implosion, which annuls differences. In the simulation of the museum, one can neutralize the distance of power: the spectators have the privilege, or maybe only the illusion, of strolling next to presidents, sovereigns and noblemen; they can infiltrate their lives and scrutinize the defects.

So much so that power, in wax museums, seems already to have been driven away, just one step away from death, because the entrance to this chamber marks the access to the pantheon of notoriety, but also to a nearby and approaching end. Since the times of Ancient Rome, in fact, wax has had a direct relationship with death: extended as a shroud on the faces of corpses, wax preserves the features for ever, bestowing on the dead the consolation of celebrity, the mirage of immortality.

The empty fortress

Untiring explorer of possible worlds, Hiroshi Sugimoto has sounded the depths of the dioramas of museums of natural science, and has contemplated the scenes of cinemas and theaters, following the subtle perimeter that separates the real from the pretend. In his last series of portraits, Sugimoto returns to the scene of the crime, to the wax museum, and shoots a gallery of dignitaries, kings, queens, revolutionaries and presidents. Fidel and Arafat, Lenin and Oscar Wilde, the Emperor Hirohito and Lady D, Queen Elizabeth, the Pope and Dalì, one next to the other; rigid, stiff as ramrods, weighed down by minute details and engulfed in black settings which almost echo the sound of muffled steps. Photographed in splendid black and white, these life-size portraits restore to the subjects the same dignity they were stripped of when they turned into mute wax mummies. But at the same time that he wraps his subjects in an aura of authenticity, Sugimoto seems to openly confess the counterfeit nature of his actions. The photographs in fact do not try to deceive our gaze: they are celebrative, shot according to the etiquette of the court portrait, but at the same time they denounce their own fiction. They keep repeating that they are nothing but wax statues. There lies the trick, under the eyes of everyone: Sugimoto bares the apparatus which upholds power: he reconstructs the set in which power moves, but he casts a glance behind the scenes.

The unbearable lightness of being

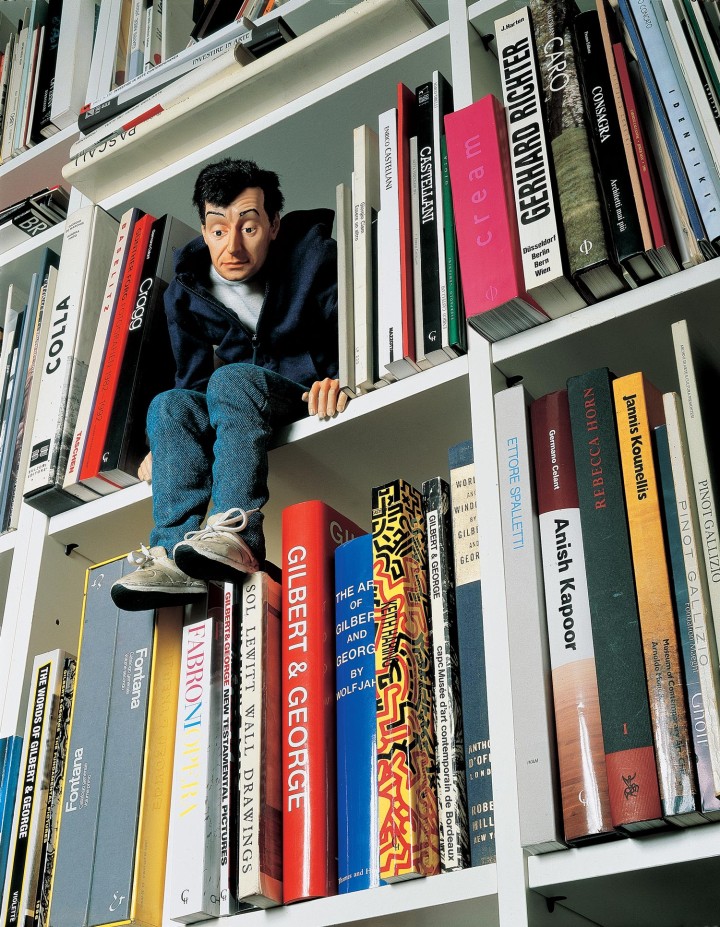

Maurizio Cattelan too has built himself a world of simulacra, masks, alter egos and puppets. In his wax sculptures however, there echoes a macabre and shocking laugh, the same sound one might hear in front of a Bosch painting or in the pages of Rabelais: a universe of grotesque excess, a carnival of fools — an upside-down world in which one drowns in a vortex of contrasting signals and half truths. His last works have become even more aggressive and direct, and it’s hard to say if they are still part of the aesthetic domain or if they belong to the ethic, the realm of the moral. But it is especially in this continuous contracting of boundaries, in this negotiation of spaces, that the sense of Cattelan’s work lies: the artist in fact has taken upon himself the responsibility of representing the world in all its complexity, in its contradictions, in good and bad, in the excesses of meaning and in the boredom of the quotidian. Like Koons, Warhol, or Kippenberger, Cattelan does not believe in the role of the artist as custodian of meaning and truth: it is his job to trigger off a situation and then to register the effects, allowing others the privilege and the sentence of taking stands. More a shaman than a clown, Cattelan explores the limits in which information and interpretation become facts. Due to this, his strategies are far from the shock and sensationalist rationale so much in vogue these years. Of course Cattelan also uses the techniques of surprise attack, of the semiotic warrior, but in his work, scandal is never gratuitous, since it is weighed by the tragedy of the absurd and transformed into problem, analyzed in its causes and in its effects.

Come and see

The wax museum and the cinema are close relatives. Born in the same city — 19th century Paris, international capital of spectacle — for some years they contended for spectatorship and newspaper pages, while exchanging inventors and intuitions. Photography stands somewhere between the two worlds. In fact, photography, like wax, sends out the smell of corpses, and entertains a privileged relationship to death. As Roland Barthes might say: it paralyses the instant but at the same time it reminds us of the inarrestable advance of time. And it is certainly no coincidence that we owe to Daguerre the invention of both the photograph and the diorama, an indispensable scenery for any wax museum, and a distant relative of cinema.

It is a kind of diorama that Piotr Uklanski composed with his The Nazis (1998), diligently aligning one hundred and sixty images and close ups of Nazi soldiers, officers and generals, taken from hundreds of films and cinema posters. In this military parade we find the faces of Harrison Ford, Roger Moore, Marlon Brando, Klaus Kinski and practically anyone who has played the role of a Nazi in either an unforgettable masterpiece or some B-movie. Fascinating, glacial, ruthless, or caricature, these faces speak to us of an absolutely contemporary disease, which forces us to give a face to evil, often skimming the boundary of the ridiculous, or worse yet, the seductive. Actually it is impossible not to be fascinated by the poses and the expressions of this platoon, which almost seem to quote Anselm Kiefer’s photographic self-portraits in Nazi poses. But if Kiefer felt the drama of history on his own skin, Uklanski reminds us that today the skin has disappeared, dissolved under the pressure of the spectacle, submerged by the voracity of vision. In other words, with his catalogue of images, Uklanski composes an anthropology of contemporary vision, and invites us to mistrust representation: “evil is not this” it seems to say. “evil is elsewhere, evil is real.” In this sense The Nazis is an admonition against the iconophilia which has contaminated the contemporary, submerging us in an excess of exchangeable images which cloud our gaze.

I shot Andy Warhol

Another story, or a legend — I don’t remember: it is night. Dennis Hopper is drunk. It happened a long time ago. Dennis Hopper has changed now, he doesn’t drink anymore. But he did then. It is night, I believe. Dennis Hopper drags himself from one room to another. He stops suddenly, takes a few steps back. Hanging on the wall is a Mao by Andy Warhol. Dennis Hopper gropes his way towards the bedroom, ruffles through the drawers, falls down and gets up. It is dark. He’s holding something, something heavy. He goes back into the other room and mutters an insult. A metallic sound. He takes a step back, another insult. A flash, maybe a passing car: the lights illuminate the scene for a moment. Hopper is armed, he has a gun. He pulls the trigger, a deafening roar: he collapses on the floor. He shoots again. This time he hits the mark. Hopper bursts out laughing. Mao continues to stare at him: he has a bullet right between his eyes, and yet he seems unmoved, indestructible. Images don’t die in a second. Guns are not enough. Images must be consumed, eroded.